UT’s Cold War Fallout Shelters

A surprise awaits those who wander into Waggener Hall. Opened in 1932 for the business school, Waggener’s outside walls are decorated with colorful terra-cotta panels that represent the exports of Texas. Cattle, oil, maize, pecans, oranges, and even a turkey, are here. Indoors, at the north end of the ground floor hallway, just above the door that leads out to the Speedway Mall, is an unusual yellow and black sign. It’s easy to miss, but 60 years ago, the campus was filled with them. This rare survivor, with its distinctive yellow triangles, is a reminder of a time when Waggener Hall was deemed a fallout shelter in case of a nuclear attack.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For several years just after World War II, the University of Texas was focused on coping with its burgeoning enrollment. In 1946, returning veterans on the G. I. Bill more than doubled the student population in just three months, from 7,900 to 17,100 students. (See: Life in Cliff Courts) Finding additional faculty, classrooms, and dorms were the top priorities, though the University community was also aware of the increasingly tense relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The U.S. monopoly on the atomic bomb, which ended the Second World War, was a short one. The Soviet Union exploded its own atomic bomb in 1949. A few years later, in 1952, the United States conducted its first test of the larger and more destructive hydrogen bomb. The Soviets followed in 1953, and in 1958 announced its deployment of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles – “ICBMs” – which made the delivery of a nuclear bomb far more efficient and harder to detect.

The U.S. monopoly on the atomic bomb, which ended the Second World War, was a short one. The Soviet Union exploded its own atomic bomb in 1949. A few years later, in 1952, the United States conducted its first test of the larger and more destructive hydrogen bomb. The Soviets followed in 1953, and in 1958 announced its deployment of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles – “ICBMs” – which made the delivery of a nuclear bomb far more efficient and harder to detect.

As the U.S. raced to defend the new threat, discussions over how to best protect the civilian population shifted away from surviving a direct hit (thought by most to be nearly impossible) to avoiding “fallout,” the radioactive dust thrown into the air by a nuclear explosion. Riding on the prevailing winds before dropping back to Earth, fallout could extend several hundred miles from the blast point, and exposure to the radiation could be fatal.

The Eisenhower administration urged building home fallout shelters, either in basements or back yards, where a family could hide from the fallout for at least two weeks. It was presumed that much of the radiation danger would have then passed, and that additional government help would be available.

As it was entirely too expensive for the government to build shelters for the entire population (a 1957 estimate in the now famous Gaither Report placed the cost at $25 billion), the Office of Civil Defense provided printed materials for families to construct and supply their own. In 1959, a 27-minute film was made available: Walt builds a Family Fallout Shelter.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

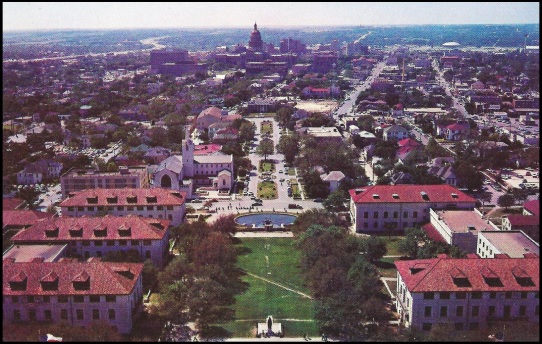

Above: The Texas Capitol, UT Tower, and downtown Austin in 1960.

In Austin, efforts to educate the public on the dangers of fallout and promote shelters began in earnest in 1960.The city was considered a prime target in a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union, as it was both the seat of Texas government and hosted Bergstrom Air Force Base just to the southeast. (Today, it’s the site of the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport.) In April, a model fallout shelter was ceremonially opened in Zilker Park. (It still exists, but is not open to the public.) With Austin Mayor Tom Miller and Governor Price Daniel on hand for the ribbon-cutting, it was the first publicly-funded shelter in Texas and part of a Civil Defense program to build a model shelter in every state. The shelter’s layout was based on one of the several do-it-yourself blueprints found in the free, 32-page Civil Defense publication The Family Fallout Shelter.

The Zilker shelter inspired UT alumnus Cactus Pryor, then working for Austin’s KTBC-TV station, to write and narrate a 20-minute film that dramatized what might happen if an atomic bomb exploded in the Hill Country just west of the city. Titled “Target . . . Austin, Texas,” it was filmed in June – with scenes in a family shelter taken at the Zilker Park model – and made its television debut on September 4. “The nature of the film is such that should a viewer tune in late he might become alarmed that the film is real,” warned the listing in the newspaper. (Watch: Target . . . Austin, Texas)

Above: The “Target . . . Austin, Texas film included a shot of an all-grass West Mall.

The Zilker facility also motivated the University’s Delta Zeta sorority, which built a new house over the summer just west of campus, near the corner of 24th and Nueces Streets. Ready by September, the “Modern Monterrey” style home was designed by the local architecture firm Page, Southerland, and Page, and featured a reinforced 1,500 square foot basement outfitted as a fallout shelter. Nationally, it was the first such shelter in college sorority house. (Delta Zeta went inactive in the 1970s and the home was purchased and is still occupied by the Delta Kappa sorority.)

In the fall of 1960, the City of Austin acquired a new director for its Civil Defense program. Colonel Bill Kengla (photo at left) first came to Austin in 1958 for a three-year post as commander of the University of Texas Naval ROTC program. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, a Marine, and a veteran of World War II, Kengla was well-received on campus, but decided to resign a year early in order to take the director position.

In the fall of 1960, the City of Austin acquired a new director for its Civil Defense program. Colonel Bill Kengla (photo at left) first came to Austin in 1958 for a three-year post as commander of the University of Texas Naval ROTC program. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, a Marine, and a veteran of World War II, Kengla was well-received on campus, but decided to resign a year early in order to take the director position.

Kengla was quite passionate about his new responsibilities and was determined to thoroughly educate and prepare the Austin area for a nuclear attack. He spoke to students at school assemblies and parents at PTA meetings. He installed 17 Civil Defense sirens across the city, including one on the top of the UT Tower, and ordered monthly siren tests. In April, 1961, Kengla convinced the organizers of Austin’s annual Flower Show to include a walk-through display of a family shelter. A month later, encouraged by Kengla, a trio of UT architecture professors conducted seminars on planning and constructing shelters in Austin, Dallas, Houston, and New Orleans.

However, despite all of the activity, the response was less than enthusiastic. Too many Austinites didn’t take the nuclear threat seriously and had no plans to ready themselves accordingly. The attitude paralleled much of the nation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the summer of 1961, the Berlin Crisis between the United States and the Soviet Union came to a head. Soviet Premiere Nikita Kruschev gave the U.S. six months to vacate isolated West Berlin. President John Kennedy’s response was to activate 150,000 armed forces reserves and increase defense expenses. On July 25, in a speech to the nation, Kennedy said, “I am requesting of the Congress new funds for the following immediate objectives: to identify and mark space in existing structures–public and private–that could be used for fall-out shelters in case of attack; to stock those shelters with food, water, first-aid kits and other minimum essentials for survival . . .” (Read and listen to Kennedy’s speech here.) The following month, the Berlin wall was erected, and soon afterward, the Soviet Union – very publicly – resumed its nuclear testing program.

The events sent a chill through the American populace, while Kennedy’s talk marked a shift in policy to promote both personal shelters as well as community shelters partly financed by government. At Kennedy’s request, Congress augmented the Civil Defense budget to about $207 million.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: A Civil Defense poster advertised “The Family Fallout Shelter” booklet.

Through the rest of 1961 and into 1962, interest in personal fallout shelters soared. Some called it the “great awakening,” others dubbed it a “revival for survival,” but newspaper reports claimed Americans everywhere were stocking up on canned goods, reinforcing basements or digging up back yards, and speaking knowledgeably about radioactive isotopes. The Family Fallout Shelter publication, which had gone largely ignored, was suddenly, insatiably popular. “We printed 20 million of those booklets in 1959,” explained Civil Defense Information Officer Joseph Quinn, “and for two years they gathered dust in local CD offices. In July, we had to print three million more just to take care of known demand.”

Through the rest of 1961 and into 1962, interest in personal fallout shelters soared. Some called it the “great awakening,” others dubbed it a “revival for survival,” but newspaper reports claimed Americans everywhere were stocking up on canned goods, reinforcing basements or digging up back yards, and speaking knowledgeably about radioactive isotopes. The Family Fallout Shelter publication, which had gone largely ignored, was suddenly, insatiably popular. “We printed 20 million of those booklets in 1959,” explained Civil Defense Information Officer Joseph Quinn, “and for two years they gathered dust in local CD offices. In July, we had to print three million more just to take care of known demand.”

The surging awareness of shelters, along with Congress’ increase in Civil Defense spending, brought with it a boon for business. “The subject of fallout shelters rates as the number one conversational topic in the nation since the nuclear test explosions conducted by Russia in the past few months,” announced the Texas Business Review, published by the University of Texas College of Business Administration (today’s McCombs School). An “immediate result of this public concern has been the recognition by the construction industry that the fall-out shelter could be very good business indeed.”

Texas newspapers were filled with shelter-related ads that marketed everything from construction materials to air filters to radiation detection kits to portable toilets. The Kinney Company touted its pre-fab shelters, showcased at the Texas State Fair, which could be delivered to a back yard and installed in a day. The Zenith Company pushed specially-designed fallout shelter clock radios, while General Mills advertised its Multi-Purpose Food, or “MPF.” Invented in the 1940s to help feed post-World War II Europe, MPF was made from fried soy grits and could be used as a high-protein additive to other foods. “One 4 ½ pound can will feed an average person for two weeks,” General Mills claimed, “and can be stored for an indefinite period.”

Texas newspapers were filled with shelter-related ads that marketed everything from construction materials to air filters to radiation detection kits to portable toilets. The Kinney Company touted its pre-fab shelters, showcased at the Texas State Fair, which could be delivered to a back yard and installed in a day. The Zenith Company pushed specially-designed fallout shelter clock radios, while General Mills advertised its Multi-Purpose Food, or “MPF.” Invented in the 1940s to help feed post-World War II Europe, MPF was made from fried soy grits and could be used as a high-protein additive to other foods. “One 4 ½ pound can will feed an average person for two weeks,” General Mills claimed, “and can be stored for an indefinite period.”

The spotlight on fallout shelters kindled debate as to whether the shelters were worth the effort and expense. Life magazine optimistically predicted that, with proper preparation, 97 percent of Americans could endure the fallout from a nuclear attack. “Your chances of surviving fallout in a big city would be good. If you are in a large apartment house or office building you could either go to the basement or an inner corridor.” In a rebuke of Life’s claims, well-known biophysicist Eugene Rabinowitz stated that a 50-percent survival rate may be “reasonable,” but only for “systematically protected populations with well-organized construction of large, deep and heavily protected stocked shelters in areas not likely to be the target for direct attack.”

In Austin, Saint Edward’s University equipped its newest building – Saint Joseph Hall for resident faculty – with a $10,000 basement shelter, while the Hilltopper student newspaper posed the ethical question: “Is the Christian required to give up his family fallout shelter to an unprepared neighbor or passing stranger?” It cited Roman Catholic Reverend H. C. McHugh, of the Jesuit monthly America magazine, who wrote, “It is the height of nonsense to say that the Christian ethic demands, or even permits, a man to thrust his family into the rain of fall-out when unsheltered neighbors plead for entrance,” then added that he doubted any Catholic moralist would condemn a homeowner who used violence to “repel panicky neighbors who applied crowbars to the shelter door.”

In Austin, Saint Edward’s University equipped its newest building – Saint Joseph Hall for resident faculty – with a $10,000 basement shelter, while the Hilltopper student newspaper posed the ethical question: “Is the Christian required to give up his family fallout shelter to an unprepared neighbor or passing stranger?” It cited Roman Catholic Reverend H. C. McHugh, of the Jesuit monthly America magazine, who wrote, “It is the height of nonsense to say that the Christian ethic demands, or even permits, a man to thrust his family into the rain of fall-out when unsheltered neighbors plead for entrance,” then added that he doubted any Catholic moralist would condemn a homeowner who used violence to “repel panicky neighbors who applied crowbars to the shelter door.”

Despite all of the media attention and promotion, a Gallup Poll taken in late 1961 found that only 12 percent of Americans planned to make changes to their homes or add shelters to prepare for a nuclear attack. This was almost double the number before the Berlin Crisis, but still well below the number wanted by Civil Defense authorities. Certainly, the U.S. population was concerned about nuclear war with the Soviet Union, but were not convinced the family shelter was the best answer or worth the personal investment.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the meantime, the U.S. government plans for community fallout shelters began to take shape. “Civil Defense is now being permanently woven into the fabric of American life,” Colonel Kengla told the Austin American-Statesman, who described a year-long national effort to identify, equip, and stock fallout shelters for 34 million persons in existing buildings. Kengla hoped to establish 350 community shelters in Austin, including 90 on the University of Texas campus.

In the meantime, the U.S. government plans for community fallout shelters began to take shape. “Civil Defense is now being permanently woven into the fabric of American life,” Colonel Kengla told the Austin American-Statesman, who described a year-long national effort to identify, equip, and stock fallout shelters for 34 million persons in existing buildings. Kengla hoped to establish 350 community shelters in Austin, including 90 on the University of Texas campus.

In late October, 1961, UT President Joseph Smiley announced a University Committee on Civil Defense, to “establish continuing contact with Civil Defense officials and other appropriate agencies.” Smiley continued, “We have a substantial responsibility to our large academic community for careful planning of precautions and procedures related to civil defense and general disaster measures.”

The seven-person committee included two members of the ROTC faculty, the campus directors of the Physical Plant (UT Facilities), Student Heath Center, Housing and Food Services, the Balcones Research Center (today’s Pickle Research Center) and an engineering professor who specialized in sanitary systems.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

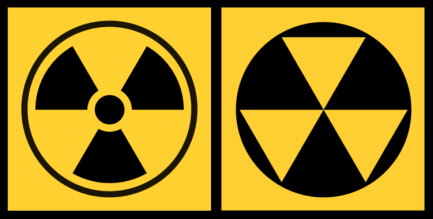

On December 1, 1961, a Civil Defense press conference formally introduced the new community fallout shelter sign. Designed by Rob Blakeley, a graphic artist with the Army Corps of Engineers, the sign was reflective yellow and black, highly contrasting colors that could be easily seen and understood in low light. Three triangles pointed downward to indicate fallout material dropping from the sky.

On December 1, 1961, a Civil Defense press conference formally introduced the new community fallout shelter sign. Designed by Rob Blakeley, a graphic artist with the Army Corps of Engineers, the sign was reflective yellow and black, highly contrasting colors that could be easily seen and understood in low light. Three triangles pointed downward to indicate fallout material dropping from the sky.

Early versions of the sign included the radiation hazard symbol, with its three blades emanating from a central atom, but the notion was rejected in favor of a sign that indicated safety rather than a warning.

Above: Radiation warning and fallout symbols.

Civil Defense Director Steuart Pittman later explained that the six outer points of the triangles signified: shielding from radiation, food and water, trained leadership, medical supplies and aid, communication with the outside world, and radiological monitoring to determine safe areas and time to return home. “It is an image we should leave with the public at every opportunity,” Pittman added, “for in it there is hope rather than despair.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Early in 1962, UT sociology professor Harry Moore released the findings of a local survey and claimed Austinites were still largely indifferent to the idea of civil defense, shelters, and warning sirens. Colonel Kengla responded, “I do not contest the survey. But I am not satisfied with community education.” Kengla believed Austin was two years behind other cities on the east and west coasts, but thought the city had a “good hard-core nucleus around which community-wide interest can be built.”

At the same time, the University Committee on Civil Defense began to work with Kengla and his staff. The group’s first project was to test the “Big Voice.”

On Saturday afternoon, April 15, a public address system installed on the 10th floor if the UT Tower shouted emergency instructions from all four sides. Kengla had seen a similar system used in Salina, Kansas and wanted to try it out on the Forty Acres. From 1 p.m. until sundown, the booming “Big Voice” issued its directives to passersby while the committee checked the effectiveness of the system’s range and acoustics. Ultimately, there were too many echoes and reverberations from other University buildings, and the “Big Voice” was abandoned.

On Saturday afternoon, April 15, a public address system installed on the 10th floor if the UT Tower shouted emergency instructions from all four sides. Kengla had seen a similar system used in Salina, Kansas and wanted to try it out on the Forty Acres. From 1 p.m. until sundown, the booming “Big Voice” issued its directives to passersby while the committee checked the effectiveness of the system’s range and acoustics. Ultimately, there were too many echoes and reverberations from other University buildings, and the “Big Voice” was abandoned.

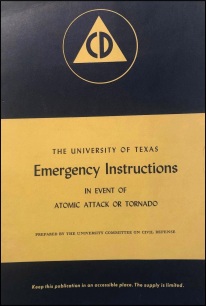

Into the summer, the Committee continued to meet and identify potential locations for campus fallout shelters, as well as to compile and publish an 8-page booklet on emergency instructions in case of a nuclear attack or a tornado. While it listed what to do in case of attack (tune in to emergency radio broadcasts, stay indoors, etc.), it had as yet no information on public shelters. The guide was published in September for the start of the new academic year and distributed to all students, faculty, and staff.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In October, the Cuban Missile Crisis once again elevated concerns over an all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union. In Austin and throughout the nation, there was a run on stores for supplies. “Housewives by the thousands crowded into neighborhood grocery stores and shopping centers searching for $2 cans of Multi-Purpose Food,” reported the Statesman. “Grocers were caught by surprise at the MPF shelves, which had remained untouched for months, suddenly emptied.” The Statesman continued, “Their husbands headed for the hardware stores, buying plastic water cans, flashlights, tools, radiological monitoring equipment, and tear gas pens.” The last item, a hand-held, writing pen-size “weapon,” would presumably be used to repel someone trying to beak in to a shelter.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: The view of the South Mall and downtown Austin in 1962 from the Tower Observation Deck.

On November 4, 1962, less than a week after the Cuban Missile Crisis ended, the University announced it had signed a contract with the Office of Civil Defense to provide 84 community fallout shelters in 30 campus buildings that would accommodate 24,099 persons. In fact, UT’s Civil Defense Committee had been working on the project for months, but the timing of the announcement was a little early, in part, to allay the fears of parents who had contacted the president’s office.

The shelters were well-distributed across the campus. Residence halls, the Main Building (which held both the central library and UT’s administrative offices), and the almost-finished Undergraduate Library and Academic Center (today’s Flawn Center) were obvious choices, along with the Texas Union, Student Health Center, and Gregory and Anna Hiss Gyms. Classroom buildings were also selected, including Garrison, Mary Gearing, Welch, Painter, and Waggener Halls, the buildings on the South Mall, and the just-completed Business-Economics Building. On the east side of campus, the Band Hall, Art Building, Drama Building, and the Law School were all deemed fallout shelters.

Above: A Civil Defense poster reminded the public that the fallout shelter sign was a “sign of protection.”

Starting in February, 1963, the designated shelters were stocked with supplies. Food, water, medical kits, radios, flashlights, batteries, soap, basic tools, portable toilets, radiation detection equipment, and walkie-talkies – which would allow for communication with emergency officials and other shelters on the campus – were all included. As with family shelters, the plan was to keep people protected and alive for two weeks.

Starting in February, 1963, the designated shelters were stocked with supplies. Food, water, medical kits, radios, flashlights, batteries, soap, basic tools, portable toilets, radiation detection equipment, and walkie-talkies – which would allow for communication with emergency officials and other shelters on the campus – were all included. As with family shelters, the plan was to keep people protected and alive for two weeks.

Photo at left: Boxed shelter supplies are loaded into the basement of the business building.

Food consisted of crackers, biscuits, or wafers, made from wheat and corn flour. The rations allowed for 10,000 calories per person staying in the shelter for two weeks, and presumed the person would be sitting or sleeping much of the time. Additional “carbohydrate supplements” were also available.

About 100 University faculty and staff volunteered to be shelter managers, one each assigned to shelters that could house 50 – 200 persons (a “space” for an individual was defined as a 10 square-foot area), and more to larger shelters. Managers completed an extensive Civil Defense-prepared training program. Basic first aid, use of the radiation and communication equipment, and how to distribute the food rations were all included, but the volunteers also learned to be crisis managers, organize the shelter population, create sleeping and medical areas, prevent radioactive contamination from outside, how to assist parents with small children, accommodate religious services, use of isometric exercises to maintain strength, and a host of other issues and situations.

On campus, the arrival of shelters received mixed reviews. The Daily Texan editorial staff published a column under the title “Better Hid than Dead” and seemed pleased that the shelters were in place. Student letters to the editor, though, expressed contrary opinions. “The specter of nuclear annihilation pales at the thought of being locked in the Union with 1,310 [the Union’s shelter capacity] Union people and surrogates,” wrote Hayden Freeman. “I’ve seen them fight for their daily bread and dread to see them fighting for their lives – I’m sure their manners won’t improve. Not only would I rather be dead than Red, I’d rather be dead than hid.” Nell Hendricks wrote, “What puzzles me about all this tomfoolery is that people seem to be taking it seriously . . . Given the ideal conditions usually postulated in CD folklore, a bomb explodes 25 miles away (the magical distance), and you simply hole up in your shelter for two weeks (the magical period). You emerge to an idyllic, pastoral existence, to rebuild a better world, facing the future free and unafraid. So runs the fairy tale. Isn’t it a pretty one? Like, who said the ostrich is a stupid bird?”

On campus, the arrival of shelters received mixed reviews. The Daily Texan editorial staff published a column under the title “Better Hid than Dead” and seemed pleased that the shelters were in place. Student letters to the editor, though, expressed contrary opinions. “The specter of nuclear annihilation pales at the thought of being locked in the Union with 1,310 [the Union’s shelter capacity] Union people and surrogates,” wrote Hayden Freeman. “I’ve seen them fight for their daily bread and dread to see them fighting for their lives – I’m sure their manners won’t improve. Not only would I rather be dead than Red, I’d rather be dead than hid.” Nell Hendricks wrote, “What puzzles me about all this tomfoolery is that people seem to be taking it seriously . . . Given the ideal conditions usually postulated in CD folklore, a bomb explodes 25 miles away (the magical distance), and you simply hole up in your shelter for two weeks (the magical period). You emerge to an idyllic, pastoral existence, to rebuild a better world, facing the future free and unafraid. So runs the fairy tale. Isn’t it a pretty one? Like, who said the ostrich is a stupid bird?”

By mid-spring, fallout shelter signs had been placed at the entrances and inside designated buildings, and the yellow and black logos became part the campus landscape.

Above: While business students prepare for the annual BBA Week, a fallout shelter sign (at far left) hangs at the entrance to the business school.

Above: A fallout shelter sign becomes part of the backdrop to a student Can-Can dance performance in front of the arched entrance to Garrison Hall.

Above: Not wanting to drill into the ornately carved limestone entrance of Welch Hall, the fallout shelter sign was posted on the brick to the upper right of the door.

Despite all of the planning, however, one glaring omission remained: there were no instructions as to which persons should go to which shelters in order to best accommodate everyone. If the Tower siren warned of a nuclear attack, should students living on campus report to their residence halls? Or, was everyone expected to simply go to the nearest shelter? What if a shelter had filled? There was no central coordination to track which shelters were still open. There could be a case where students, studying on the South Mall when the siren blew, had to frantically dash from building to building to find an available space. What if an attack came at night? Who would unlock the University buildings? Certainly, shelter managers weren’t expected to leave their families and try to make their way to campus. In addition, as UT’s shelters were public, they weren’t limited to the University community. In an emergency, a visitor on campus was expected to make use of them.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: The Business-Economics Building.

It wasn’t until late in the year that a simulation run of a fallout shelter was planned. On Thursday afternoon at 1 p.m., December 5, 1963, 40 volunteer shelter managers descended into the basement of the Business-Economics Building, or “BEB.” Opened the previous year, it was the largest classroom facility on Forty Acres. The basement level was reserved for student activities, with space for lounges, recreation, student organization meeting rooms, and the largest assembly of vending machines on the campus, including a newfangled dollar bill changer. (See The Big Enormous Building).

The volunteers were part of the latest shelter manager training group and had just completed nine weeks of classes. They limited themselves to the south portion of the basement so as not to disrupt too much of the usual student activity. In a real emergency, the BEB basement was the University’s largest shelter, with a capacity of 4,400 persons.

For the eight-hour simulation, it was presumed that Bergstrom Air Force Base had just been hit in a nuclear attack and that fallout was drifting northwest over Austin. John Gaulding, on staff at the University’s Personnel Office, was elected shelter manager for the exercise.

“Radiation in Austin increasing, keep shelter closed tightly,” said bulletin number 3 from Austin’s Civil Defense headquarters, which was in radio contact with the group. Professor John Scanlan, who directed the nuclear reactor laboratory in the Engineering Science Building, served as radiation monitoring captain for the day. He unpacked the radiation detection kit from the shelter’s supplies and determined that there were no radiation leaks. As the simulation continued, Civil Defense regularly updated the outdoor conditions.

“Radiation in Austin increasing, keep shelter closed tightly,” said bulletin number 3 from Austin’s Civil Defense headquarters, which was in radio contact with the group. Professor John Scanlan, who directed the nuclear reactor laboratory in the Engineering Science Building, served as radiation monitoring captain for the day. He unpacked the radiation detection kit from the shelter’s supplies and determined that there were no radiation leaks. As the simulation continued, Civil Defense regularly updated the outdoor conditions.

A volunteer patient was brought in to the shelter, checked for radiation and treated for broken bones. The group spread cardboard boxes on the floor as hospital beds and improvised with strips of cardboard as splints. Large sheets of paper became blankets.

Above left: The standard Civil Defense provisions for a 50-person fallout shelter included 10 drums of water and boxes of food, medical, sanitation, and radiation detection supplies that could be stacked in a space 40 inches square. The BEB basement shelter was equipped to handle 4,400 persons. Image courtesy of the Cold War Museum online.

Gladys Hudnall, the Food Services Supervisor at Kinsolving residence hall, acted as food and water captain and distributed paper cups filled with water from the supplies. Each person saved their cup for future use and was allotted a quart of water a day. The evening mealtime was served at 4:45 p.m., when the volunteers received eight crackers apiece as their caloric ration.

After dinner, there were isometric and other muscle exercises, and discussion on sleeping preparations. The sleeping arrangement captain, Neil Taylor, who was the manager of the Chuck Wagon diner in the Texas Union (what today is the Cactus café), selected the best ventilated area for sleeping. In a real situation, single men and women would have been placed at opposite ends, with married couples and children in the middle. Whatever bedding that was available would have been shared.

The following day, Mattie Treadwell, the chief field officer from the Washington, DC headquarters of Civil Defense, told the Texan that UT’s simulation was the first conducted by a large university. “I hope that other schools will be inspired to try similar exercises.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And then, nothing. After the 1963 simulation, there were no more records of training sessions for shelter manager volunteers. No one was designated to check the status of the food and medical supplies. Nationally, interest in fallout shelters dropped dramatically and Congress cut the Civil Defense budget accordingly. By 1975, twelve years after the fallout shelter signs were first hung, the Texan reported that the University was clearing out the shelter supplies to create more storage space. The medical provisions only had a four-year shelf life and had long since expired. Some of the food containers were opened, but the crackers and wafers were declared “rancid” and discarded. What could be salvaged was returned to Civil Defense.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, most of the outdoor fallout shelter signs, by then either rusted or bleached by the Texas sun, were removed from University buildings.

Sources:

Briscoe Center for American History (UT Archives): UT President’s Office Papers, Civil Defense files

Blanchard, Boyce Wayne. American Civil Defense 1945: The evolution of Programs and Policies (Dissertation, University of Virginia, 1980)

Marten, James. Coping with the cold War: Civil Defense in Austin, Texas 1961-62 (East Texas Historical Journal, March 1988)

The Texas Business Review, January 1962, pg. 9-10 (University of Texas College of Business Administration)

University of Texas Emergency Instructions in event of Atomic Attack or Tornado (1962) Special thanks to Avrel Seale who found a copy in the University Communications office and photographed the contents.

Office of Civil Defense publications: Ten for Survival: Survive a Nuclear Attack (1959), The Family Fallout Shelter (1959), Federal Civil Defense Guide – Fallout Shelter Food Requirements (1962), Shelter Manager Instructor Guide (1963), Guide for Community Fallout Shelter Management (1963)

Civil Defense Museum online: http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/

Life magazine, September 15, 1961, pg. 95-108

Newspapers: The Daily Texan, Austin American-Statesman, St. Edward’s University The Hilltopper, Fort Worth Star Telegram, Fresno Bee, Provo Daily Herald, San Angelo Standard Times, Sioux City Journal, Wichita Falls Times