Of the many and varied traditions that pervade American campus life, none is as prevalent or pronounced as a college’s colors. Often so closely allied with a university’s name, it’s difficult to imagine one without the other. At the sight of bold blue, Yale alumni often remember their alma mater, while the combination of blue and maize invites graduates of the University of Michigan to recall their favorite student memories. Dartmouth claims forest green, Princeton touts orange and black, Nebraska boasts scarlet and cream. The colors brighten football stadiums on crisp autumn afternoons, embellish official university seals, dramatically illuminate campus landmarks, and are draped in abundance at spring commencements. Along with the printed name of a college, its colors are the signature visual element that binds generations of students and alumni to their university.

The origins of most college colors coincide with the arrival of intercollegiate athletics in the mid-nineteenth century, but their individual histories are as diverse as the colors themselves. At a New England regatta in 1858, Harvard crew members Benjamin Crownshield and Charles Elliot hurriedly supplied crimson bandanas to their teammates so that spectators could easily distinguish them in a race. Elliot was named Harvard’s 21st president in 1869, and served in that capacity for four distinguished decades. In 1910, the year after he retired, crimson was officially named the University’s color. Through much of its early history, students at the University of North Carolina were required to join either the Dialectric or Philanthropic Literary Societies, and sported colors to declare their membership. The Di’s color was light blue, the Phi’s opted for white. When UNC fielded its first athletic teams, the combination of white and Carolina blue was the obvious choice to represent the University. At the University of Virginia, silver gray and cardinal red had been used since the Civil War, symbolic of a Confederate uniform dyed in blood. But as college sports became more popular in the 1880s, student leaders voiced concerns, claimed the colors were inappropriate for athletic contests, and believed the gray was “lacking in durability.” In 1888, UVA students held a mass meeting to settle the matter. Allen Potts, a star athlete on the football team, attended the gathering wearing a blue and orange scarf he’d acquired during a summer boating expedition at Oxford University. A fellow student pulled the scarf from Potts’ neck, waved it to the crowd and asked, “How will this do?”

The origins of most college colors coincide with the arrival of intercollegiate athletics in the mid-nineteenth century, but their individual histories are as diverse as the colors themselves. At a New England regatta in 1858, Harvard crew members Benjamin Crownshield and Charles Elliot hurriedly supplied crimson bandanas to their teammates so that spectators could easily distinguish them in a race. Elliot was named Harvard’s 21st president in 1869, and served in that capacity for four distinguished decades. In 1910, the year after he retired, crimson was officially named the University’s color. Through much of its early history, students at the University of North Carolina were required to join either the Dialectric or Philanthropic Literary Societies, and sported colors to declare their membership. The Di’s color was light blue, the Phi’s opted for white. When UNC fielded its first athletic teams, the combination of white and Carolina blue was the obvious choice to represent the University. At the University of Virginia, silver gray and cardinal red had been used since the Civil War, symbolic of a Confederate uniform dyed in blood. But as college sports became more popular in the 1880s, student leaders voiced concerns, claimed the colors were inappropriate for athletic contests, and believed the gray was “lacking in durability.” In 1888, UVA students held a mass meeting to settle the matter. Allen Potts, a star athlete on the football team, attended the gathering wearing a blue and orange scarf he’d acquired during a summer boating expedition at Oxford University. A fellow student pulled the scarf from Potts’ neck, waved it to the crowd and asked, “How will this do?”

For the University of Texas, the choice of orange and white was an extended and sometimes precarious journey that began almost as soon as the campus was opened, and ended with most of the students disappointed in the final result.

~~~~~~~~~~

When the University of Texas opened in 1883, baseball – not football – was the sport of choice for UT students, and afternoon inter-class games were played on the relatively flat northwest corner of the Forty Acres. The team waiting to bat often took shade under one of the old trees that are today known as the Battle Oaks.

In the spring of 1885, the latter half of UT’s second academic year, a student enrolled who claimed to have the only curve ball pitch in the state. The curve ball was a new addition to the game, welcomed by baseball progressives, hated by the sport’s purists. Nevertheless, students eagerly formed a team “that rated high in brain power, low in brute force,” and challenged any college in Texas to a game. Southwestern University, 30 miles north in Georgetown, answered the call and invited UT to a picnic and baseball contest. The University accepted, and students arranged to make the trip to Georgetown on a chartered train.

It was a cloudy and gloomy Tuesday morning, April 21, 1885, when the baseball team, along with most of the student body, arrived at the downtown Austin train station at Third Street and Congress Avenue (photo at left), and boarded passenger cars bound for Georgetown. Mrs. Helen Marr Kirby, the University’s Lady Assistant, accompanied the group to chaperone the co-eds. Everything was on schedule until the final whistle sounded. Just as the train was ready to depart, Miss Gussie Brown from (of all places) Orange, Texas, urgently announced the need for some ribbon to identify themselves as UT supporters.

It was a cloudy and gloomy Tuesday morning, April 21, 1885, when the baseball team, along with most of the student body, arrived at the downtown Austin train station at Third Street and Congress Avenue (photo at left), and boarded passenger cars bound for Georgetown. Mrs. Helen Marr Kirby, the University’s Lady Assistant, accompanied the group to chaperone the co-eds. Everything was on schedule until the final whistle sounded. Just as the train was ready to depart, Miss Gussie Brown from (of all places) Orange, Texas, urgently announced the need for some ribbon to identify themselves as UT supporters.

Today’s college fans arrive at stadiums clad in t-shirts and caps. But in the 1880s, colored ribbons were worn on lapels to show team loyalty. The more enterprising male students sported longer ribbons, so they would have extra to share with a pretty girl who had none. The truly ingenious (or just plain desperate) wore ribbons almost down to their knees.

Two of Gussie’s friends, Venable Proctor and Clarence Miller, always ready to impress the ladies, jumped off the train and sprinted a half block north along Congress Avenue to Carl Baryman’s General Store. Between gasps for breath, they managed to ask the shopkeeper for three bolts of two colors of ribbon. “What colors?” the shopkeeper inquired. “Anything,” was the response. After all, the train was leaving the station, and there was no time to be particular.

The shopkeeper gave them the colors he had the most in stock: white ribbon, which was popular for weddings and parties and was always in demand, and bright orange ribbon, because no one bought the color, and the store had plenty to spare.

Loaded with their supplies, Proctor and Miller hustled back and boarded the moving train as it left for Georgetown. Along the way, the ribbon was evenly divided and distributed to everyone except for a law student named Yancey Lewis, “who had evolved a barbaric scheme of individual adornment by utilizing the remnants.”

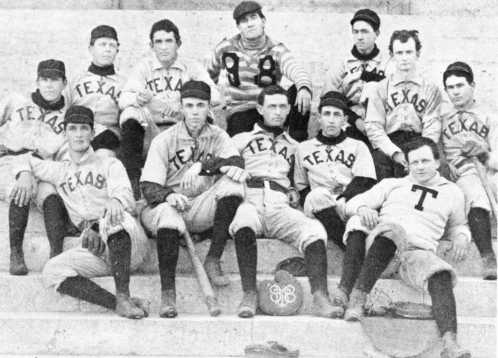

Above: The 1898 University of Texas baseball team.

Unfortunately, it rained much of the afternoon, the curve ball curved not, and Texas outfielders ran weary miles in a lost cause. The score was a lopsided 21 – 6 win for Georgetown. According to one witness, the University’s colors were “christened on a dire and stricken field.”

Or were they? Even though the first baseball team had sported orange and white, the colors were by no means official, and subject to the whims of future UT students.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

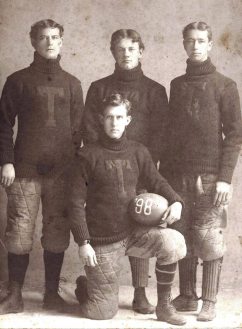

Above: The 1893 University of Texas football team.

After a decade of starts and stops, the University of Texas fielded its first “permanent” football team in 1893. The first recorded game was actually ten years earlier, during UT’s inaugural fall term, though it was a rather embarrassing two-goals-to-none loss against a group of high school students at the private Bickler School in downtown Austin. Football, the newfangled sport that could draw 50,000 spectators to a Princeton-Yale game in the 1880s, required a little more time to be accepted in the Lone Star State.

The UT football team of 1893 played four games, a pair in the fall and two more in the spring. The first was against the Dallas Foot Ball Club, which claimed to be the best in the state. Held at the Dallas Fair Grounds, the game attracted a record 1,200 onlookers. It was a tough and spirited match, but when the dust had settled, the “University Eleven” had pulled off an 18 – 16 upset. “Our name is pants, and our glory has departed,” growled the Dallas Daily News. The UT club would go on to a spotless record and earn the undisputed boast of “best in Texas.”

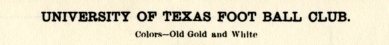

A close-up view of the 1893 UT vs. Dallas football program, which listed the University’s colors as Old Gold and White.

But the squad from Austin didn’t wear orange. While their black and white uniforms almost exactly matched those worn by their foes from Dallas, the UT footballers had donned yellow caps. More important, the program for the game declared the University’s colors to be “old gold and white.”

In the 1890s, the UT campus consisted of a still-unfinished Victorian-Gothic Main Building, a chemical lab building to its northwest, and a plain-looking men’s dorm, known as Brackenridge Hall, or B. Hall, nestled down the hill to the east. All were fashioned from pale yellow Austin pressed brick, and trimmed with cream-colored limestone quarried in nearby Cedar Park. (The Gebauer Building, built in 1904 for engineering, is today the home for College of Liberal Arts, and is the last survivor of this early UT architecture.) Students identified themselves with their surroundings on the campus, and several University teams donned gold and white uniforms.

Above: The Forty Acres in 1898. From left, Chemistry Labs, an unfinished old Main Building, and B. Hall, the men’s dorm. All were constructed from yellow-buff brick and limestone trim.

Of course, gold and white weren’t official, either, and only lasted a year. Members of the UT Athletic Council wanted a more “masculine” color, and in 1894 orange was paired with white once more. But athletes and equipment managers began to complain about team uniforms. The orange was “unstable” and had a tendency to bleed during washing, while the white soiled quickly and was difficult to clean. In 1898, to save cleaning costs, the Athletic Council opted for a darker color that wouldn’t show dirt as easily: maroon.

For the next two years, UT football, baseball, and track uniforms, along with letter sweaters, were orange and maroon, and the hues were incredibly popular with UT students. Soon after the colors made their appearance, maroon caps with orange T’s were available for $1.25 in stores along Congress Avenue. (For those worried about any similarity to the colors used in College Station, Texas A&M teams sported red at the time. Maroon wasn’t adopted by the Aggies until the 1930s.)

For the next two years, UT football, baseball, and track uniforms, along with letter sweaters, were orange and maroon, and the hues were incredibly popular with UT students. Soon after the colors made their appearance, maroon caps with orange T’s were available for $1.25 in stores along Congress Avenue. (For those worried about any similarity to the colors used in College Station, Texas A&M teams sported red at the time. Maroon wasn’t adopted by the Aggies until the 1930s.)

Right: 1898 UT football players were wearing maroon sweaters with orange T’s.

While orange and maroon may have been a hit with the students in Austin, the sudden change was more than controversial among the alumni. By 1899, a stranger to a University of Texas home football game might have wondered if there weren’t multiple teams pitted against the visiting squad, as UT fans displayed orange and maroon, orange and white, and gold and white ribbons on their lapels.

In the spring of 1900, after considerable discussion, the Board of Regents decided to hold an election to settle the matter. Students, faculty, staff and alumni were all invited to send in their ballots. Out of the 1,111 votes cast, 562 were for orange and white, a majority by just seven votes. Orange and maroon receive 310, royal blue 203, crimson 10, royal blue and crimson 11, and few other colors scattered among the remaining 15 votes.

In the spring of 1900, after considerable discussion, the Board of Regents decided to hold an election to settle the matter. Students, faculty, staff and alumni were all invited to send in their ballots. Out of the 1,111 votes cast, 562 were for orange and white, a majority by just seven votes. Orange and maroon receive 310, royal blue 203, crimson 10, royal blue and crimson 11, and few other colors scattered among the remaining 15 votes.

Over the next three decades, UT athletic teams wore bright orange on their uniforms, which usually faded to a yellow by the end of the season after having been washed a few times. By the 1920s, other college teams sometimes called the Longhorn squads “yellow bellies,” a term that didn’t sit well with the athletic department. A recent discovery has shown that in 1925, UT football coach “Doc” Stewart ordered uniforms in a darker shade of orange that wouldn’t fade, and would later become known as “burnt orange” or “Texas Orange.” The dark-orange color remained in use into the 1940s, when shortages during World War II made the dye unavailable. UT uniforms reverted to bright orange for another two decades, until coach Darrell Royal revised the burnt orange color in the early 1960s.

Wow this is extremely interesting

Thanks!

We were just discussing this on Saturday. Now we know.