The University’s World War I service flag is 100-years old March 2nd.

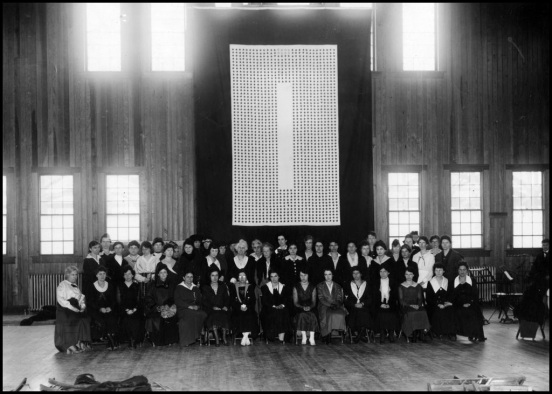

Above: A century ago, on March 2, 1918, a hand-sewn, 10 1/2 x 16 foot World War I service flag was presented to the University.

It’s nine pounds of wool and grommets that tells a story like no other.

Among the extensive collections preserved by the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, a 10 ½ x 16 foot relic from UT’s past is a poignant reminder of a time when normalcy on the Forty Acres was upended and replaced by a single-minded effort to aid the country at war. While universities have often described their missions in terms of education, research, and service, the First World War required the University of Texas to put almost everything else on hold and focus on its service to the nation.

One of the many wartime projects was the creation of an enormous University service flag. A team of faculty wives and UT co-eds carefully hand-cut and sewed more than 1,500 stars – on each side – to honor members of the University community enlisted in the armed forces. Officially presented on March 2, 1918 as part of UT’s Texas Independence Day celebration, the flag is a century old this year.

~~~~~~~~~~

World War I was a defining moment for American higher education. Before 1917, colleges and universities were viewed by many to be frivolous or elitist, not as opportunities for social and economic mobility. Professors were rarely asked for advice on issues or problems of the day. Despite curriculum reforms to include more “practical” courses in science and engineering, and business — along with the more traditional Greek, Latin, and the classics — colleges in the early 20th century had failed to win widespread support from government, business, and the public. The world war changed everything.

Caught up in the patriotic fervor that pervaded the nation, male students rushed to enlist in the armed forces, which decimated college enrollments. At co-ed institutions like the University of Texas, women assumed leadership roles that had traditionally been denied to them. Professors who specialized in subjects useful for war were recruited for their expertise.

Caught up in the patriotic fervor that pervaded the nation, male students rushed to enlist in the armed forces, which decimated college enrollments. At co-ed institutions like the University of Texas, women assumed leadership roles that had traditionally been denied to them. Professors who specialized in subjects useful for war were recruited for their expertise.

To avoid the closure of hundreds of male-only colleges, a national Student Army Training Corps was created, which allowed students to both remain in school and receive military instruction. Because the corps was open to any high school graduate, legions of young men who might otherwise have joined the work force found themselves on a college campus, and either graduated or returned after the war to finish their degrees.

By the end of the conflict, universities had firmly established themselves in the public eye as a national resource. The college campus became a place where American youth could be transformed into broadly-educated and valued citizens.

~~~~~~~~~~

In Austin, the entry of the U.S. into the First World War on April 6, 1917, transformed campus life almost immediately. Unsure where to begin, the faculty promptly organized itself into a military company. Led by philosophy professor Al Brogan as honorary captain, 84 professors agreed to participate in one hour of drill and shooting practice three days a week. The group included honorary Private and UT President Robert Vinson. Senior members who were too old for active military training assisted history professor Eugene Barker with planting a war garden.

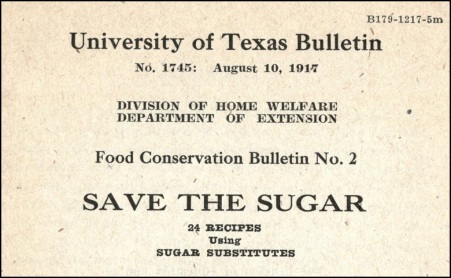

The faculty, of course, did much more than drill. Almost 40 professors were granted leaves of absence to engage in government service, often in officers’ training camps, hospitals, or intelligence. On campus, research in psychology, biology, and chemistry was directed toward the war effort. Home economics professor Mary Gearing organized a widely-touted war college for Texas women that focused on food production and conservation, as well as women in wartime industrial roles. With funding from the Department of Agriculture, Gearing dispatched groups of UT co-eds to rural areas across the state to instruct farmers on the best methods for food preservation. At the same time, the University produced four widely-distributed bulletins with recipes to help conserve food staples.

The faculty, of course, did much more than drill. Almost 40 professors were granted leaves of absence to engage in government service, often in officers’ training camps, hospitals, or intelligence. On campus, research in psychology, biology, and chemistry was directed toward the war effort. Home economics professor Mary Gearing organized a widely-touted war college for Texas women that focused on food production and conservation, as well as women in wartime industrial roles. With funding from the Department of Agriculture, Gearing dispatched groups of UT co-eds to rural areas across the state to instruct farmers on the best methods for food preservation. At the same time, the University produced four widely-distributed bulletins with recipes to help conserve food staples.

Above: The “Save the Sugar” bulletin was one of four in a series. Other bulletins were filled with recipes – created and tested on campus – to conserve wheat, meat, and fat.

Most notable, perhaps, was chemistry professor James Bailey (photo at left). As a UT undergraduate, Bailey was better known as one of the authors of the University’s first yell, but after completing his Ph.D. at the University of Munich, he returned to Austin as a professor of organic chemistry. In 1915, when war broke out in Europe, medical supplies of the anesthetic drug Novocaine quickly ran short. The drug had been discovered in Germany, which wasn’t going to share the formula with its wartime enemies. Bailey volunteered to help, worked with Alcan Hirsch in New York, and “rediscovered” both Novocaine and a synthetic Adrenalin, a significant contribution to the war effort for all of the Allies.

Most notable, perhaps, was chemistry professor James Bailey (photo at left). As a UT undergraduate, Bailey was better known as one of the authors of the University’s first yell, but after completing his Ph.D. at the University of Munich, he returned to Austin as a professor of organic chemistry. In 1915, when war broke out in Europe, medical supplies of the anesthetic drug Novocaine quickly ran short. The drug had been discovered in Germany, which wasn’t going to share the formula with its wartime enemies. Bailey volunteered to help, worked with Alcan Hirsch in New York, and “rediscovered” both Novocaine and a synthetic Adrenalin, a significant contribution to the war effort for all of the Allies.

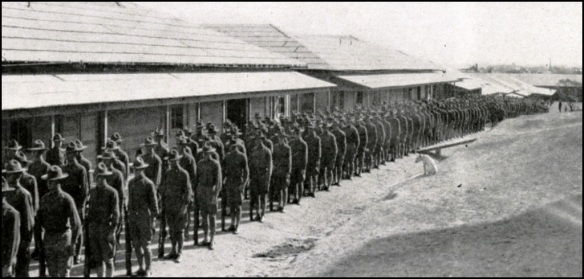

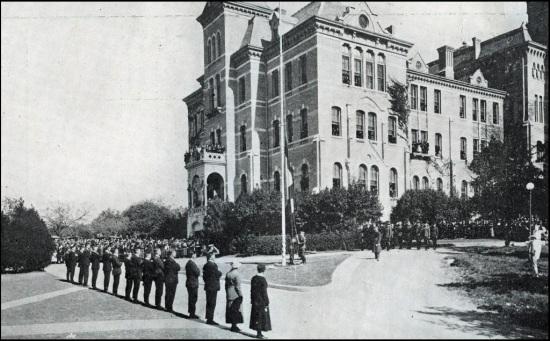

In 1917, over 1,000 UT students rushed off to enlist, but with the advent of the Student Army Training Corps a year later, campus enrollment again swelled to accommodate those who were concurrently students and members of the U.S. Army. The Forty Acres was converted into an armed encampment, as students in uniform woke to the sounds of “Reveille,” marched in formation to meals, and followed a strict schedule that included both academics and military training. Sentries were posted at University buildings, and professors were required to present proper identification to enter their offices and classrooms.

Above: Members of the UT Student Army Training Corps fall in to formation in front of a row of wooden barracks along the west side of Speedway (where Waggener Hall and the McCombs School are today). On the hill to the right, Pig Bellmont, UT’s first live mascot, inspects the troops.

In late April 1917, President Vinson was appointed to the Council of National Defense and requested to attend a strategic conference in Washington, D.C. The meeting formalized an idea supported by President Woodrow Wilson to better involve universities in the war effort. In order to take advantage of existing college facilities and instructors, the U. S. government established special military schools for aviators at campuses throughout the country. Six colleges were initially chosen to host a School of Military Aeronautics (SMA), and the University of Texas was among them. The SMA was to provide basic technical instruction for beginning pilots before they moved on to flight training. An eight-week session included classes in the history and theory of flight, meteorology, astronomy, machine guns, aerial combat, and the use of signal flags in communication. Those attending the SMA were soldiers in a new branch of the Army known as the “Air Service,” later to become the Air Force, and were not considered university students. Instructors for the SMA included both army officers and UT professors.

Above: The official flag of UT’s School of Military Aeronautics is still preserved in the University Archives, a part of the Briscoe Center.

The SMA opened in June 1917. It was first housed in B. Hall, the first men’s dorm, but the SMA quickly grew from 50 students to several hundred. It was moved to more spacious quarters in buildings once used by the state’s Blind Institute, now called the “Little Campus,” just north of the Erwin Center, where Hargis Hall and the Nowotny Building remain. When the war ended, the SMA had expanded to almost 1,200 students. The largest in the country, it was given the nickname “West Point of the Air,” and was a prototype for the U. S. Air Force Academy.

Above: The School of Military Aeronautics in formation on the Little Campus. Only the building on the left remains as today’s John Hargis Hall, used for Freshman Admissions.

The success of the School for Military Aeronautics placed the university in good stead with the War Department, which assigned two additional schools to the Austin campus. The School for Automobile Mechanics opened in March 1918 at Camp Mabry in northwest Austin. Three hundred men at a time completed a six-week course before being sent overseas to the war. Like the SMA, instructors included members of the university faculty.

A month later, the School for Radio Operators was established on the campus. It took over the B. Hall quarters vacated by the SMA, but needed more classroom space than was available. To solve the problem, several rows of large canvas army tents were pitched in front of the old Main Building (photo at right), along what is now the South Mall. Once opened, radio students and their equipment were a common sight on the hilltops and in the valleys west of Austin.

A month later, the School for Radio Operators was established on the campus. It took over the B. Hall quarters vacated by the SMA, but needed more classroom space than was available. To solve the problem, several rows of large canvas army tents were pitched in front of the old Main Building (photo at right), along what is now the South Mall. Once opened, radio students and their equipment were a common sight on the hilltops and in the valleys west of Austin.

~~~~~~~~~~

One of the by-products of World War I was the invention of the service flag (photo at left). Designed by Robert Queissner, an Army captain from Cleveland, Ohio, the rectangular banner featured a blue star on a white background with a red border. Queissner initially created and displayed a pair of flags as a patriotic tribute to his two sons, who were in France fighting on the front line. But the idea quickly became popular nationally, and service flags were visible on front doors, in living room windows and on Main Street storefronts. Each blue star represented a son or daughter enlisted in the armed forces during wartime. If a person died in service, the blue star was covered with a gold one.

One of the by-products of World War I was the invention of the service flag (photo at left). Designed by Robert Queissner, an Army captain from Cleveland, Ohio, the rectangular banner featured a blue star on a white background with a red border. Queissner initially created and displayed a pair of flags as a patriotic tribute to his two sons, who were in France fighting on the front line. But the idea quickly became popular nationally, and service flags were visible on front doors, in living room windows and on Main Street storefronts. Each blue star represented a son or daughter enlisted in the armed forces during wartime. If a person died in service, the blue star was covered with a gold one.

In February 1918, members of the University Ladies Club — spouses, daughters, sisters, and mothers of UT faculty and staff — decided that the University of Texas needed a service flag of its own, one large enough to display blue stars to honor all of the faculty and alumni engaged in the war effort. Spearheaded by the wife of engineering professor Ed Bantel, the Ladies Club recruited the Women’s Council, a student organization for UT co-eds, and discussed plans for an ambitious project.

Above: The University ladies Club and the Women’s Council work on the service flag.

The flag required a full two weeks of labor, with volunteers divided into 15-person shifts. Made from “a fine grade French flannel,” the entire flag measured 10 1/2 x 16 feet. The white center was 6 1/2 x 12 feet, and was initially filled with 1,570 blue stars. Each was 1 1/2 inches tall, individually traced, cut, placed, and hand sewn in meticulous straight lines. While Captain Queissner’s original service banner was intended to be hung against a wall or in a window, with the blue star visible only on one side, the ladies elected to make the university’s version a true flag, so that two star fields were created, attached back-to-back, and a two-foot wide red border sewn around it.

Above: The University’s service flag was presented on March 2, 1918.

Ready by March 2nd, the flag was introduced at the University’s Texas Independence Day ceremonies in the old wooden gym that pre-dated Gregory Gymnasium. Following a rousing rendition of “The Stars and Stripes Forever” by the UT Band, Charlotte Spence, chair of the Women’s Council, formally presented the flag to the university. Space was left for 140 additional stars, and, instead of a gold-colored material, eight of the stars had white toppings to indicate those who had died. Before the war was over, the remaining stars would be added (more faculty and alumni served in the war than the flag could accommodate), and 85 stars would be topped in white.

Once completed, the service flag was a popular public symbol of the university’s commitment to the war effort, and was proudly displayed in the rotunda of the Old Main Building. On rare occasions it was attached to the outer brick walls of the old Main Building for commencement and other ceremonies.

Above: Patriotism Day on Nov. 14, 1919. The service flag is carefully lowered from the University’s flag pole. Click on an image for a larger view.

One year after the war ended, on Friday, November 14, 1919, the university held a “Patriotism Day” memorial. At noon, in accordance to “General Order No. 1 as issued by President Robert Vinson,” classes were dismissed, and all students, faculty and staff assembled in military style in front of Old Main, where, for the first and only time, the service flag had been hung on the university’s flag pole.

Engineering dean Thomas Taylor acted as commanding officer. The names of University men and women who lost their lives were read, “Taps” was heard, and as the band played “The Star Spangled Banner,” the flag was slowly lowered, folded, and solemnly carried into the Library (now Battle Hall) to be stored in the archives.

What an incredible insight into the sacrifice so many men and women made to create a future for the University and the nation we all too frequently take for granted. Thank you, Jim, for the excellent article! Keep ‘em coming! Hook ‘em!