Fifty years ago, UT students considered replacing the Longhorn mascot.

It was never meant to be taken quite so seriously. On Tuesday, November 2, 1971, the University’s Student Senate unanimously approved a resolution, introduced and supported by Student Body President Bob Binder, to poll UT students about switching the University’s mascot from the longhorn to the armadillo.

The idea originated the previous August at the annual National Student Association conference, where student leaders from neighboring states were divided into regions. Those from Texas and Oklahoma were considered the “Greater Southwest,” but they didn’t care much for the moniker and opted instead to call themselves the “Armadillos.” The name resonated with Binder and the other UT students who attended the conference, and they wondered if a mascot change might have some interest on the Forty Acres.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The nine-banded armadillo – dasypus novemcinctus – is a medium-sized, mostly nocturnal mammal that feeds on insects and grubs rooted from the ground by the claws on its forefeet. As anyone who has seen one knows, an armadillo’s most recognizable trait is the tough bony shell that protects most of its body like a shield of armor. Actually, “armadillo” is a Spanish term that translates as “little armored one.”

The nine-banded armadillo – dasypus novemcinctus – is a medium-sized, mostly nocturnal mammal that feeds on insects and grubs rooted from the ground by the claws on its forefeet. As anyone who has seen one knows, an armadillo’s most recognizable trait is the tough bony shell that protects most of its body like a shield of armor. Actually, “armadillo” is a Spanish term that translates as “little armored one.”

Though its appearance might not be all that impressive, a ‘dillo is not without its talents. It can hold its breath for nearly six minutes – probably developed after keeping its snout buried in the ground for long periods searching for food – and when it needs to forge a creek, there’s no need to swim. The armadillo simply holds its breath and saunters across the creek bottom. If startled or threatened, it can launch itself three or four feet in the air or run short distances up to 30 miles-per-hour, faster than an Olympic sprinter. The former is likely meant to surprise a potential predator and give the ‘dillo a few moments to scamper to safety, but when an armadillo crosses a busy Texas road and is scared by a passing car, a jump up and into the underside of the vehicle is often, unfortunately, deadly.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On campus, news of the Senate’s resolution was met with shock, disbelief, and laughter. Head Football Coach Darrell Royal chuckled with no additional comment, while quarterback Donnie Wigginton responded with a long, incredulous “why?” Some students voiced their support of the idea. “I think it’s great. I do. I think we need a change,” stated one student in The Daily Texan. “I think it’s just student attitudes towards the system. I like it,” echoed another. “The armadillo represents the state of Texas as well as the longhorn,” said a third, “they’re all over the highway, too.”

On campus, news of the Senate’s resolution was met with shock, disbelief, and laughter. Head Football Coach Darrell Royal chuckled with no additional comment, while quarterback Donnie Wigginton responded with a long, incredulous “why?” Some students voiced their support of the idea. “I think it’s great. I do. I think we need a change,” stated one student in The Daily Texan. “I think it’s just student attitudes towards the system. I like it,” echoed another. “The armadillo represents the state of Texas as well as the longhorn,” said a third, “they’re all over the highway, too.”

Alumni were less accommodating, and Binder’s mailbox was soon full of letters from unhappy UT graduates: “The prospect of having an armadillo as a mascot may amuse some of the students, but I’m sure I speak for several thousand Texas Exes when I tell you that we are, very definitely, not amused.” Another was less tactful, “I have heard of some fantastically idiotic happenings at the University of late but this has to be the most blasphemous piece of rot that ever crept across the campus.”

The news media had a field day. Not only did newspapers and TV stations across Texas carry the story, it was mentioned as far away as Orlando, Florida, north to the town of Petoskey, Michigan, and west to the California coast. The University of Texas, after all, had been named national football champions for the past two years, in 1969 and 1970. For the Longhorns to consider trading in their iconic image for the humble armadillo was, well, news.

Above: Headlines from the nation’s newspapers.

When asked, Binder claimed that the armadillo was a “peaceful and ecologically-minded animal, and cheaper to maintain than a longhorn.” The comment fit well with the times. University students were caught up the activism of the late 1960s and early ‘70s, including civil rights and anti-war protests, women’s liberation, and the ecology movement, where pro-environment political action had led to the passage of the Clean Water Bill and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. On campus, students had already made international news over their protest against the removal of trees along Waller Creek (see The Battle of Waller Creek) and had unofficially named the new East Mall Fountain, “Peace Fountain.”

Pervasive as it was around Central Texas, the ‘dillo had also gained a following in Austin. The Armadillo World Headquarters, opened in 1970, quickly became the city’s best-known music venue, and when the Austin American-Statesman’s Capital 10,000 race debuted in 1978, “Dash the ‘Dillo” was the event mascot.

Pervasive as it was around Central Texas, the ‘dillo had also gained a following in Austin. The Armadillo World Headquarters, opened in 1970, quickly became the city’s best-known music venue, and when the Austin American-Statesman’s Capital 10,000 race debuted in 1978, “Dash the ‘Dillo” was the event mascot.

Still, not everyone on the Forty Acres was convinced. “I fail to see why an insect-eating armadillo is more ‘peaceful’ than a grass-eating steer,” opined one UT student, while another thought that the Student Senate “might have more important things to worry about.” Texan columnist Hartley Hampton pointed out that, “Bob Binder is a peaceful and ecologically-minded animal, and cheaper to maintain than a longhorn,” and promptly suggested that Binder be the new mascot.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

As the fall semester progressed, the ‘dillo debate continued, though much of it more sarcastic than serious. The Friday after the Senate approved its resolution, a football rally was held in Gregory Gym where many of the students attended holding images of armadillos mounted on poles. Chants alternated between “Texas Fight!” and “Root ‘em ‘Dillos!” But when head cheerleader Jose Pena asked the crowd if there were any UT Armadillos present, the answer was a resounding “No!”

An Armadillo Marching Band was organized with 40 students in the ranks and with internationally-respected psychology professor (and future Plan II director) Ira Iscoe as the group’s faculty advisor. The band made several well-received appearances, but eschewed traditional musical instruments in favor of kazoos, washboards, and spoons. “We don’t say we favor the change in mascot, but we do believe in the armadillo,” one of the members explained. A letter to the Texan was a bit more candid: “As an indication of the overall attitude of the band, it might be noted that were the University mascot in fact changed, in all probability this organization would immediately disband and transfer to the local agricultural institution.”

Above: A pair of orange-painted ‘dillos on Kyle Field.

Texas A&M supporters were eager to voice their preferences. The Thanksgiving Day football game between the University and A&M was held that year in College Station. At the start of halftime, a pair of armadillos (above), splashed with orange paint and with “TU” written in white on their backsides, was released on Kyle Field just as the Longhorn Band was about to perform. According to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “one was picked up by an assistant Texas band director and carried off the field while the other high-tailed it toward the Longhorn cheerleaders. He knew where he belonged.” The pranksters were thought to be Aggie freshmen. No matter. At the end of the game, UT had prevailed 34-14, won the Southwest Conference title, and earned a berth in the Cotton Bowl to face Penn State.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: “Texas Armadillos” bumper stickers were popular in Austin.

With all of the interest surrounding the ‘dillo debate, it was inevitable that some would want to cash in on an opportunity. Less than two weeks after the Senate passed its resolution, local entrepreneurs were selling three varieties of bumper stickers: two displayed the words “Texas Armadillos” with a pair of fierce-looking ‘dillos on each side, printed either orange on a white background or white on orange, and a “Root ‘em Armadillos” sticker printed white on orange. The stickers were carried by the University Co-op (and elsewhere) and quickly became bestsellers. It wasn’t long before the bumper stickers were seen throughout Austin.

Above: Days after UT’s football team won the Southwest Conference and was going on to the Cotton Bowl to play Penn State, “Dig ’em ‘Dillos” bumper stickers were being sold in stores along the Drag.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

After the start of the New Year, discussion about the mascot had run its course and all but vanished. The idea received plenty of attention, but it was never fully supported on campus, and the Student Senate didn’t follow through with its poll. Besides, replacing the longhorn required approval of the Board of Regents, which was unlikely. There were, though, a couple of reminders.

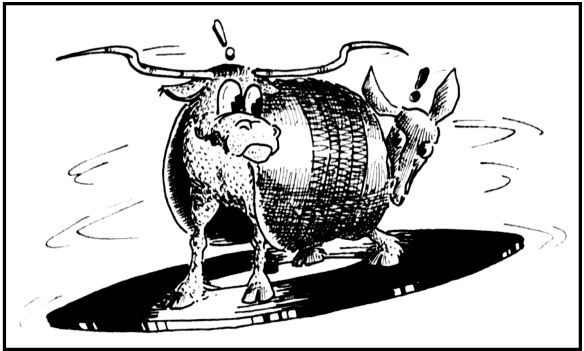

In late January, 1972, country music singer-songwriters (and married couple) Mitch Torok and Ramona Redd composed a song that offered a compromise solution, a merger of both longhorn and armadillo, called “The Texas Hornadillo, Part 1 & 2.” Torok explained, “We thought it might be good to resolve matter through a song and a little humor.” A record was produced by Torok’s Calico Records in Houston, and the song performed by the Orange and White Barroom Singers and Dancers, Class of ’49. The recording included voice impersonations of Coach Darrell Royal, several Texas politicians, and “the head of the Institute of Texas Animal Crossbreeding.” The “Hornadillo” was available in record stores statewide and was occasionally heard on the radio.

In late January, 1972, country music singer-songwriters (and married couple) Mitch Torok and Ramona Redd composed a song that offered a compromise solution, a merger of both longhorn and armadillo, called “The Texas Hornadillo, Part 1 & 2.” Torok explained, “We thought it might be good to resolve matter through a song and a little humor.” A record was produced by Torok’s Calico Records in Houston, and the song performed by the Orange and White Barroom Singers and Dancers, Class of ’49. The recording included voice impersonations of Coach Darrell Royal, several Texas politicians, and “the head of the Institute of Texas Animal Crossbreeding.” The “Hornadillo” was available in record stores statewide and was occasionally heard on the radio.

Above left: A Ben Sargent cartoon of the “Hornadillo” appeared in the Austin American-Statesman.

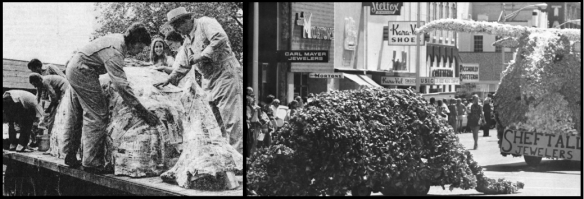

Toward the end of the semester, at what was then the Round-Up Parade down Guadalupe Street and Congress Avenue, the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority and Acacia fraternity teamed up to construct one of 17 floats in the parade: a longhorn steer – made from chicken wire and papier-mache – accompanied by an armadillo. The float won Best Overall honors.

Above: A Round-Up Parade float that featured both a longhorn and armadillo was named “Best Overall”.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Not all was lost for the modest armadillo. In 1978, students at Oak Creek Elementary School in Houston asked the Texas Legislature to name the ‘dillo the official state mascot. Their senator, Jack Ogg, sponsored a resolution, but despite a growing number of supporters from all parts of Texas, the Legislature resisted both in 1979 and 1981. One senator described the armadillo as a “God-awful animal.”

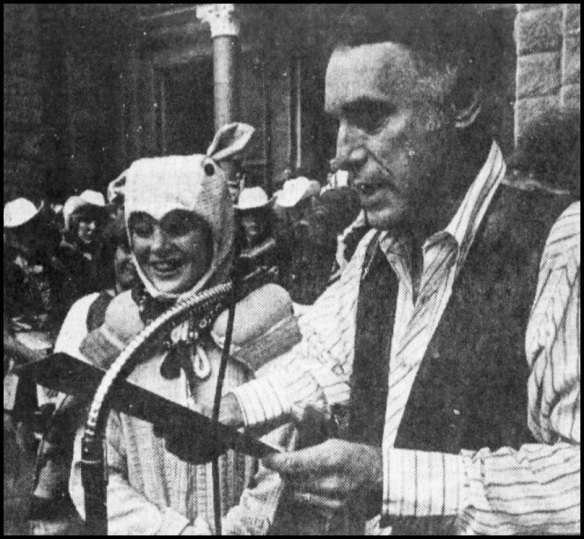

Ogg (photo at left), though, served as president pro tempore of the Senate, and on October 3, 1981, with the governor and lieutenant governor both out of the state, Ogg was sworn in as “governor for a day.” Traditionally, this was an honorary position, but Ogg dedicated his brief administration to “the most important people in the state – our children,” and issued an executive decree naming the armadillo as the Texas mascot. Ogg signed the proclamation “because it is important that [the children] see the system work.”

Ogg (photo at left), though, served as president pro tempore of the Senate, and on October 3, 1981, with the governor and lieutenant governor both out of the state, Ogg was sworn in as “governor for a day.” Traditionally, this was an honorary position, but Ogg dedicated his brief administration to “the most important people in the state – our children,” and issued an executive decree naming the armadillo as the Texas mascot. Ogg signed the proclamation “because it is important that [the children] see the system work.”

Eventually, the reluctance of the Legislature softened. In 1995, lawmakers officially designated the ‘dillo as the “small mammal of Texas.” What was the large mammal? The longhorn, of course.

Thanks Jim. Appreciate the history lesson.

Hook Em Horns,

Bill Martin

A great story !