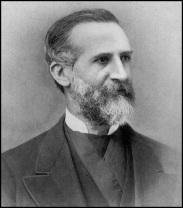

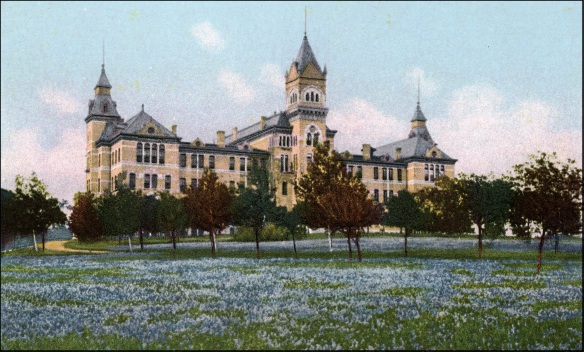

Above: The earliest known image of the UT campus, taken in 1883 at the present intersection of University Avenue and Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard. The west wing of the old Main Building – where the Tower stands today – is the only structure.

One hundred and forty years ago, the University of Texas opened not to the blare of trumpets and fanfare, but to the chatter of neighs and whinnies.

It was a sunny, sticky, Saturday morning, September 15, 1883, when nearly 300 persons gathered at 10 a.m. for the opening ceremonies of the new University. The men dressed in dark three-piece suits and popular bowler or derby hats, while the women donned colorful bustle dresses with matching, fashionable headwear.

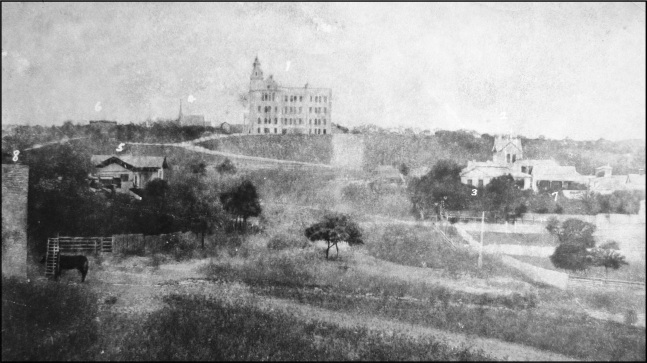

The group assembled in what was the unfinished west wing of the old Main Building and sat on chairs arranged on a makeshift floor of undressed lumber, surrounded by unpainted walls. The incomplete windows were open to the elements, which required the day’s speakers to compete with the brays and snorts – and odors – of the many horses hitched outside.

The west wing sat near the center of a square, uneven, 40-acre campus, initially dubbed “College Hill.” It was almost devoid of flora, save for a thicket of mesquite trees and a handful of live oaks, some festooned with Spanish moss. A great gully extended from the top of the hill to the southeast, dry most of the time but a muddy torrent in wet weather. According to Halbert Randolph, who earned his law degree in 1885, the ornamental shrubbery consisted of a “cactus sporting its full-grown fruit, looking like the ripe nose of a drunkard.” For a few weeks in the spring, the campus was aglow with a blanket of Texas bluebonnets, and the pitiable state of the grounds was temporarily forgotten.

Above: The west wing of the old Main Building, about 1885. Victorian Gothic in style, it was made from yellow pressed brick with limestone trim, and had a grey slate-tiled mansard roof. Plumbing for the building was incomplete. Almost out of sight and behind the hill to the right is the roof of a temporary lavatory.

To the east, beyond the University grounds, lay vast tracts of pasture land and open prairie. Just to the west, along a dusty and unpaved Guadalupe Street, stood two grocery stores, a dry goods shop, and a saloon.

The sprawling town of Austin filled the view to the south, its 11,000 inhabitants still abuzz over the local telephone service that was installed two years earlier. Austin won the privilege to host the main campus of the University after a hotly contested state election, and as it was already the seat of Texas government, civic leaders predicted Austin would soon be the “Athens of the Southwest.”

Fortunately, there were no proposals to change the city’s name accordingly. Harvard University, opened in 1638 in the village of New Town, Massachusetts, was founded by a group of University of Cambridge alumni with high hopes for the college, and New Town was promptly renamed Cambridge. The trend continued into the 19th century, as the United States expanded westward. Colleges and universities were desired assets of newly-started, up-and-coming towns with lofty ambitions, and communities sometimes renamed themselves to reflect their goals. It’s no accident that two of Ohio’s state universities reside in towns named Oxford and Athens, that students enrolled at the University of Mississippi travel to Oxford, or that the University of Georgia is located in Athens.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

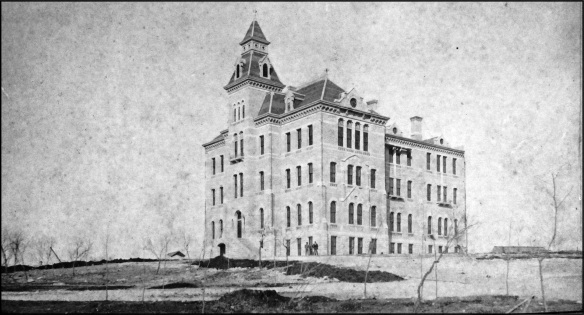

Ashbel Smith, a 76-year-old physician from Galveston (photo at left), was selected to chair the University’s inaugural Board of Regents, and was entrusted with the Herculean task of creating the new university. A graduate of Yale, Smith was a secretary of state for the Republic of Texas and served multiple terms in the state legislature.

In the final years of his life, Smith’s passion was the University of Texas, and his top priority was to recruit the best faculty possible. Smith traveled extensively, visited colleges throughout the country, and spent many late nights devoted to University-related correspondence. His letters, scribbled by candlelight, are now carefully preserved in the University archives.

After nearly two years of effort, Smith and the Board of Regents selected eight professors. Six of them formed the Academic Department, and most were assigned to teach multiple disciplines: English, literature, and history; chemistry and physics; mathematics; metaphysics, logic, and ethics; ancient Greek and Latin; and Spanish, French and German. The remaining two faculty members composed the Law Department. Salaries averaged $2,500 per year, a generous sum in the 1880s.

Most of the professors hailed from Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky. To save on travel expenses, Smith convened the first faculty meeting in May 1883 not in Austin, but at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

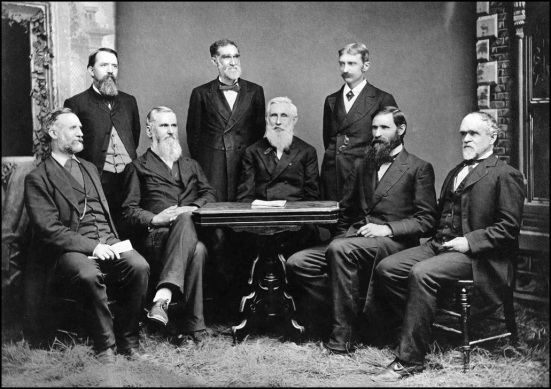

Above: The University’s first faculty. From left: John Mallet, professor of physics and chemistry; Leslie Waggener, professor of English language, history, and literature; Robert Dabney, professor of mental and moral philosophy and political science; Robert Gould, professor of law; Oran Roberts, professor of law; Henri Tallichet, professor of modern languages; Milton Humphreys, professor of ancient languages; and William LeRoy Broun, professor of mathematics.

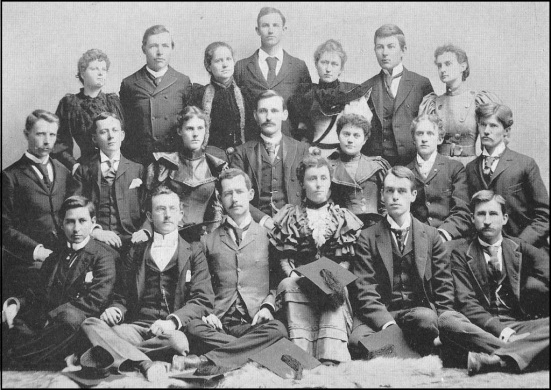

The initial entrance requirements were determined by the faculty. Candidates for the Academic Department were expected to know elementary Greek and Latin, though French and German could be substituted for those planning to pursue science or literature. Competency in algebra and plane geometry, English composition, history, and political geography were also required. Admission to the law department did not yet require a bachelor’s degree, though candidates were urged to have a strong background in reading and writing English, and a “familiarity of the history of the United States and England.”

In the weeks before the University was scheduled to open, college-aged youth made their way to Austin to present their credentials and be interviewed by the faculty for admission. In a state where 90 percent of the population was classified as rural, many of the candidates were from farms and ranches, the children of pioneers, raised in log cabins with few luxuries. They were practical and self-motivated, but their preparatory education was incomplete. Many did not possess high school diplomas, and the standards for admission were too high. One prospective student who hoped to study mathematics, when asked how much math he had taken, proudly responded that he’d completed a class in “discount and bankruptcy.” Though hindered by a lack of formal education, the young Texans managed to impress the faculty. According to chemistry professor John Mallet, “Boys whose spelling and arithmetic were much behind their years, talked and thought like grown men of house building on the prairie, of cattle driving, even of social and political movements.” At the end of the first day of entrance examinations, the faculty met, discussed the situation, and with a collective shrug decided not to rigidly enforce the “grade of scholarship” established for admission, due to the “limited advantages for education in this state.”

From the beginning, the University was open to women, a progressive statement at a time when opportunities for women in higher education were rare. That UT would be co-educational was the result of a compromise in the state legislature as it debated the bill to create the University. Some members of the House who were opposed to female students were also political opponents of Governor Oran Roberts, and they feared that Roberts, whose term in office was coming to a close, would be named UT’s first president. In order to support the inclusion of women, the legislators demanded that the University be modeled after the University of Virginia, which was then led by a faculty chairman instead of a chief executive. An agreement was reached. Women were admitted as students, but for its first decade, University affairs were the responsibility of the elected head of the faculty. Roberts was denied the possibility of serving as UT’s president, but he was appointed one of the two initial law professors.

While the 1876 Texas constitution mandated the creation of the University, it also required the legislature to “establish and provide for the maintenance of a College or Branch University for the instruction of the colored youths of the state,” which denied the Austin campus to African Americans. It would take another 70 years, starting with the 1950 enrollment of Heman Sweatt in the School of Law, for the University to truly become of and for all Texans.

~~~~~~~~~~

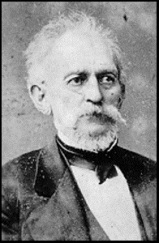

Among the speakers for the opening ceremonies was Dr. John Mallet (photo at left). Hired away from the University of Virginia to teach chemistry and physics, Mallet was elected by his fellow UT professors to be the first Chair of the Faculty.

Among the speakers for the opening ceremonies was Dr. John Mallet (photo at left). Hired away from the University of Virginia to teach chemistry and physics, Mallet was elected by his fellow UT professors to be the first Chair of the Faculty.

Mallet cautioned those present not to expect too much too soon, and prophetically compared the progress of a university to the growth of a tree. “It must have a fruitful field . . . but you will be disappointed if you expect it to grow from the seedling to the proportions of a stately tree in a single night. And more will you be disappointed if, in your efforts to hasten its growth, you pluck it up by the roots to see how much the roots have grown.” Mallet also spoke of the students, “to whom the faculty look with peculiar interest and hopes,” and then, directly to the students in the audience.

To the students: “We ask you to be fellow workers with us. You should try to understand your true relations to the University. You frequently hear the phrase used, ‘coming to the university,’ not remembering that you are the university. More than the faculty – more than the Board of Regents – more than all else – it is the students that make the university. It is not the crumbling stones of Oxford, nor the memories of its hundreds of able teachers that make it the great university of England, but it is the never dying intellectual and moral life of the five and twenty generations of men who have gathered there as students. The students are, in the highest and truest sense, the university themselves.

“If Texas is to have a university of the first class, worthy of the name, the work of the faculty can form but a small part in its success. Its development must be the result of the united efforts of the people of Texas, of the State government, of the Board of Regents, of the faculty, and above all, of the students of the university.”

With an incomplete building, sitting on a mostly barren campus, boasting an inaugural faculty of eight professors, and joined by 221 students, the University took its first, tentative steps upon the stage of Academe.

Excellent general history!