When UT’s Athletes Proudly Wore Maroon

It was a great day for the second-ever football game between the University of Texas and Texas A&M. Partly cloudy skies and temperatures in the low 70s greeted fans who gathered at the University’s athletic field – unofficially dubbed “Athletic Park” by the newspapers – on Saturday afternoon, October 22, 1898. The teams hadn’t met in four years since their initial match in 1894, and a large crowd was expected. A few bleachers on the west side accommodated around 200 spectators, but most of the fans stood along the sidelines several persons deep. It would be another decade before UT students built their first stadium. (See The One Week Stadium)

It was a great day for the second-ever football game between the University of Texas and Texas A&M. Partly cloudy skies and temperatures in the low 70s greeted fans who gathered at the University’s athletic field – unofficially dubbed “Athletic Park” by the newspapers – on Saturday afternoon, October 22, 1898. The teams hadn’t met in four years since their initial match in 1894, and a large crowd was expected. A few bleachers on the west side accommodated around 200 spectators, but most of the fans stood along the sidelines several persons deep. It would be another decade before UT students built their first stadium. (See The One Week Stadium)

University supporters arrived in suits, ties, and bowler hats for the men, and colorful Victorian dresses and fashionable hats for the women. As was the custom of the time, fans showed their team loyalty by wearing orange and white ribbons on their lapels, though enterprising male students wore longer ribbons so they could “snip and share” with any coeds who had none.

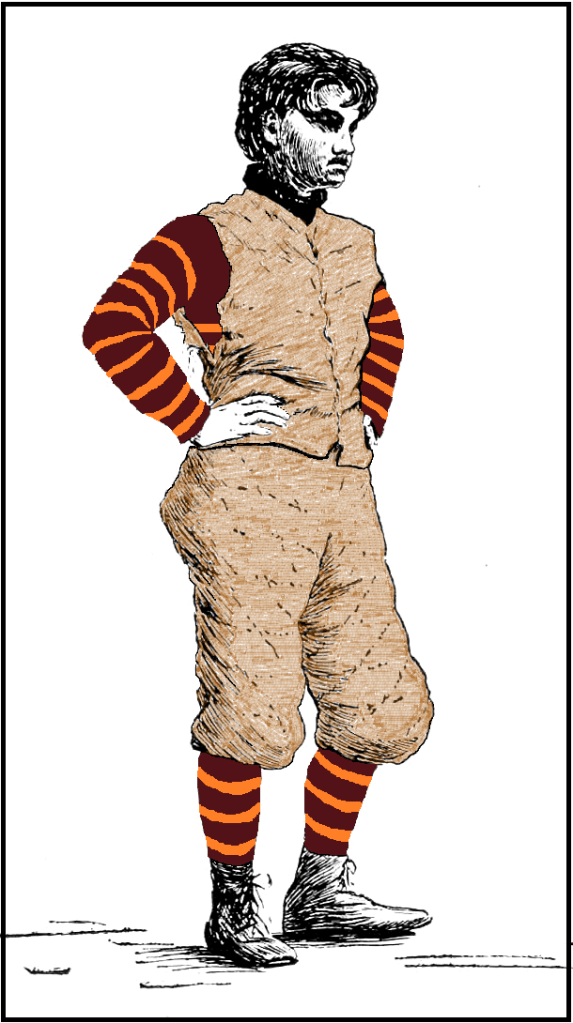

Above left: A UT football player in his orange and maroon uniform. This is actually a sketch found in the 1897 Cactus yearbook and (poorly) colored by the author. Look closely – there is no helmet. In the 1890s, most football players had long, bushy hair and believed it would be sufficient to protect the head.

About 75 members of A&M’s Corps of Cadets rode a chartered train from College Station, accompanied by a similar number of rooters. The cadets were armed with a variety of noise makers, from cow bells to dinner bells to tin horns, and everyone sported bright red and white ribbons, which were then the colors of the A&M College.

Kick-off was set for 3 o’clock, and it wasn’t long before the audience realized the game would be a lopsided one for a UT win. The reporter covering the game for the Austin Daily Statesman had an apparent fondness for simile. He wrote, “The ‘Varsity boys played like champions, and went through the visitors like a temperance resolution at a prohibition convention,” which was followed immediately by, “Touch-downs were as numerous as pretty new bonnets on a well-developed Easter morning.” The final score was 48–0.

The talk of the game, though, wasn’t the tally on the scoreboard, but the UT uniforms. While University fans dutifully showed up with their traditional orange and white, the team ran onto the field in orange and maroon.

The reaction, though, may not have been what you expected.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: The 40-acre University of Texas campus in 1895 consisted of the old Main Building (center) only two-thirds complete, the Chemistry Labs building to the left, and B. Hall, the first men’s residence hall, to the right.

By any measure, John Otis Phillips was a BMOC, a Big Man on Campus. Tall with dirty blonde hair, his parents hailed from the northeast United States (Rhode Island and New York), though Phillips was born and partly raised in Calcutta, India, then sent with his brother William to the Oberlin Preparatory Academy, a private boarder school managed by Oberlin College, Ohio, about 30 miles west of Cleveland. Phillips continued on to the College for two years before he transferred to the University of Texas as a 21-year old junior in 1895. Once in Austin, he settled into a room at a boarding house just west of campus, at 2002 San Antonio Street, and then promptly dived deep into University life

By any measure, John Otis Phillips was a BMOC, a Big Man on Campus. Tall with dirty blonde hair, his parents hailed from the northeast United States (Rhode Island and New York), though Phillips was born and partly raised in Calcutta, India, then sent with his brother William to the Oberlin Preparatory Academy, a private boarder school managed by Oberlin College, Ohio, about 30 miles west of Cleveland. Phillips continued on to the College for two years before he transferred to the University of Texas as a 21-year old junior in 1895. Once in Austin, he settled into a room at a boarding house just west of campus, at 2002 San Antonio Street, and then promptly dived deep into University life

Engineering Dean Thomas Taylor described Phillips as, “the smoothest and easiest political boss that ever hit the campus. He readily earned the title of ‘Old Smooth and Easy.’” Phillips graduated in 1897 with a BA in English, studied history and political science for two years (he essentially had a bachelor’s degree with a triple major), and then entered law school in 1899. But along the way, Phillips was vice-president of his junior class and president of his senior class, president of the Tennis Club, ran on the UT track and field team, was treasurer of the University YMCA, the first vice-president of the newly-organized University Co-op, president of the University Athletic Association, a member of the Athletic Field Club (which worked to purchase the land University students were already using for football, baseball, and track), a member of the Bicycle Club, business manager for the student-published University of Texas Magazine, business manager of the Cactus yearbook, twice business manager of The Ranger student newspaper (which preceded The Texan), and twice, in 1897 and 1898, manager of the football team. His status as BMOC might better be described as “Business Manager on Campus.”

Above: The 1897 UT football team sits for a group photo on the front steps of the old Main Building, most wearing their letterman sweaters – white pullovers with orange “T’s.” As was tradition, team captain Dan Parker sat in the middle with the football, young mascot Billie Batts, son of law professor Robert Batts (Batts Hall’s namesake) seated just below, Coach Mike Kelly to the left of Parker wearing his green and white Dartmouth “D” letter sweater of his alma mater, and John Phillips, team manager, to the right wearing a coat.

In the 1890s, before a professional athletic director and staff managed intercollegiate sports on a university campus, the responsibility was taken up by volunteers. On the Forty Acres, an Athletic Council of three professors, three alumni, and three students oversaw UT’s needs for intercollegiate men’s football, baseball, track and field, and later, tennis. (Women’s sports, including basketball, tennis, and field hockey, were added for a time in the 1900s before women’s physical training director Anna Hiss pulled back from intercollegiate competition.)

Assisting the Athletic Council were student team mangers for each sport. As the football team manager, Phillips had to: correspond with team managers at other universities to arrange a schedule and agree upon a share of gate receipts or guarantees (a monetary guarantee was crucial for the visiting team to afford its travel costs), purchase train tickets and make hotel/meal reservations for all out-of-town games, hire a coach (with the Council’s approval), order and maintain uniforms and equipment, secure a place for a “training table” – usually a restaurant or boarding house where the team ate the kinds of meals prescribed by the coach (think athletes’ cafeteria), and oversee publicity, game receipts, and the team budget.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On Tuesday morning, September 20, 1898, the Athletic Council met in the old Main Building. The fall term was to begin the following Monday, September 26, and football practice for anyone interested in trying out for the team was to start the same day. At the top of the agenda, though, was the need for a coach. Mike Kelly, the previous year’s coach, had been hired by the University to oversee the new gymnasium in Old Main’s north wing (see UT’s First Gymnasium) and teach physical training classes.

The Council took a chance and hired David Edwards, an 1896 Princeton University graduate. At the time, Princeton was one of the “Big Four” – along with Harvard, Yale, and Chicago – as college football powerhouses. While Edwards had been a football standout, his coaching debut was less than stellar. In 1897, he guided Ohio State to a dismal 1-7-1 record (which is still the Buckeye’s worst season) and fired. However, Edwards had strong recommendations from Princeton and had spent the summer learning more about coaching at his alma mater. Mike Kelly was retained as assistant coach and would run practices until Edwards arrived by train the first week of October.

The Council took a chance and hired David Edwards, an 1896 Princeton University graduate. At the time, Princeton was one of the “Big Four” – along with Harvard, Yale, and Chicago – as college football powerhouses. While Edwards had been a football standout, his coaching debut was less than stellar. In 1897, he guided Ohio State to a dismal 1-7-1 record (which is still the Buckeye’s worst season) and fired. However, Edwards had strong recommendations from Princeton and had spent the summer learning more about coaching at his alma mater. Mike Kelly was retained as assistant coach and would run practices until Edwards arrived by train the first week of October.

Ten days later, on Saturday evening, October 1, the Council gathered again in Old Main. Coach Edwards was due in Austin on Wednesday the 5th and would take over the team the following day. The first football game of the season was set for October 15 at Add-Ran College (later Texas Christian University) in Waco. The team, though, had a uniform problem.

Phillips, who was starting his second season as football manager and was one of the three students on the Athletic Council, explained that the orange and white jerseys were difficult to maintain. When they were washed, the orange stripes sometimes bled over to the white, while the white itself was easily soiled and difficult to clean. There was also a contingent on campus – which included some of the team – that thought the color white too weak, that it represented “surrender” and ought to be replaced with another, stronger hue.

After an extended discussion, and without notifying the University president or anyone else, the Council authorized Phillips to replace white with a darker color of his choosing, one that would better conceal dirt stains. Black was out, as orange and black were Princeton’s colors. So was blue, as blue and orange had been used by the University of Virginia for a decade. Instead, Phillips selected maroon. This was the University of Chicago’s color, but not in combination with orange. “After discussing at length the question of uniforms for the team,” reported the San Antonio Light, “the Council instructed Mr. J. O. Phillips, the manager of the football team, to order at once 18 jerseys, 12 pairs of football shoes, 12 pairs of trousers, 6 nose guards, 1 dozen footballs and 12 pairs of stockings.” (Many accounts wrongly claim that it was Coach Edwards who tried to change UT’s colors, but the colors were chosen and the uniforms ordered before Edwards arrived in Austin.)

Orange and maroon striped jerseys arrived about two weeks later, too late for the first game on October 15, a 16-0 win over Add-Ran College, where the team wore their usual orange and white. Instead, the jerseys were introduced at the first home game a week later against the A&M College of Texas.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

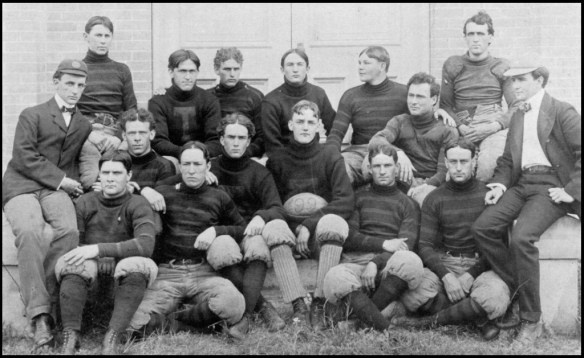

Above: The 1898 UT football team with most wearing their letter sweaters – maroon with orange “T’s.”

The day after the A&M game, the Austin Daily Statesman remarked, “The football colors are now maroon and orange, which makes a pretty combination,” and most of UT’s 504 students agreed. The new colors were a hit. There was a sudden rush for maroon and orange ribbons at the general stores downtown before the next home game the following Saturday, October 29, when Galveston’s football club came to Austin. The Statesman predicted the “game will be replete with an abundance of snap and vim on the part of the maroon and orange.” The University won 17-0, remained undefeated, and had its third straight shutout. (The 1898 team finished with a respectable 5-1 record, though Edwards decided against coaching for a career and returned to New Jersey to become a lawyer. His brother, Edward, served as the state’s governor in the 1920s.)

By early November, maroon mania had swept the campus, while the city’s merchants rushed to respond. The University Co-op, then located underneath the central staircase of Old Main, sold maroon and orange badges to be worn at football games. Maroon hats with orange bands were available for $1.25 in shops along Congress Avenue. Phillip Hatzfeld’s store, which specialized in women’s fashions, advertised “Orange and maroon ribbon in correct shades. ‘Varsity colors.” (At the time, ‘varsity was a nationally used contraction of the word university.)

By early November, maroon mania had swept the campus, while the city’s merchants rushed to respond. The University Co-op, then located underneath the central staircase of Old Main, sold maroon and orange badges to be worn at football games. Maroon hats with orange bands were available for $1.25 in shops along Congress Avenue. Phillip Hatzfeld’s store, which specialized in women’s fashions, advertised “Orange and maroon ribbon in correct shades. ‘Varsity colors.” (At the time, ‘varsity was a nationally used contraction of the word university.)

The University’s sophomore and junior classes of 1900 and 1901 went a step further and voted to have “class hats.” Similar to jockey caps or rounded baseball caps, they were made from henrietta – a woolen fabric – and lined with gray satin. “A group of wearers presents a pretty picture, for the maroon is quite showy,” remarked the Statesman. “For the juniors, the figures ’00, and for the sophomores, the figures ’01, have been worked in orange silk just above the [bill]. The example set is good, and it is hoped other classes will follow it.” Not to be outdone, the 1899 senior law class opted for collapsible maroon top hats with orange bands.

The University’s sophomore and junior classes of 1900 and 1901 went a step further and voted to have “class hats.” Similar to jockey caps or rounded baseball caps, they were made from henrietta – a woolen fabric – and lined with gray satin. “A group of wearers presents a pretty picture, for the maroon is quite showy,” remarked the Statesman. “For the juniors, the figures ’00, and for the sophomores, the figures ’01, have been worked in orange silk just above the [bill]. The example set is good, and it is hoped other classes will follow it.” Not to be outdone, the 1899 senior law class opted for collapsible maroon top hats with orange bands.

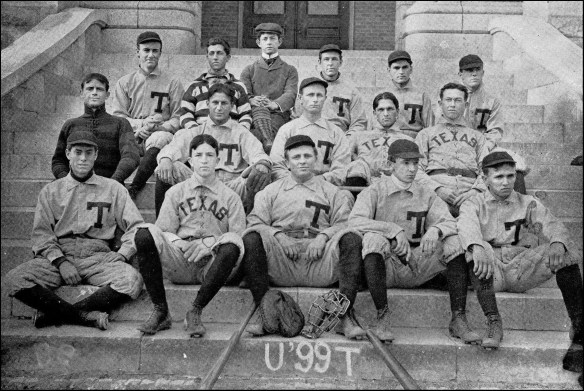

Above: The 1899 baseball team on the front steps of Old Main, with maroon socks and hats, and orange “T’s” on their jerseys.

The following spring, the baseball team found itself in new attire. “The caps are of maroon material, with an orange ‘T.’ The shirts are gray with an orange ‘T’ on the breast,” said the University Calendar. “The pants are likewise gray. Maroon stockings, with orange stripes, and substantial shoes complete the outfit.” The 1899 football team followed their predecessors and kept the popular colors, which had clearly become more than a fad. Even the 1899 Cactus yearbook had a maroon cover.

Above: The 1899 UT football team poses for a group photo in back of Old Main. Players are in their striped jerseys or letter sweaters. Assistant manager Allen Barton, on the left end in a suit, wears a maroon cap with an orange circle and maroon “T” above the bill that was available in the shops downtown. On the right end, team manager Rich Franklin wears his 1900 maroon class cap, with an ’00 in orange on the front.

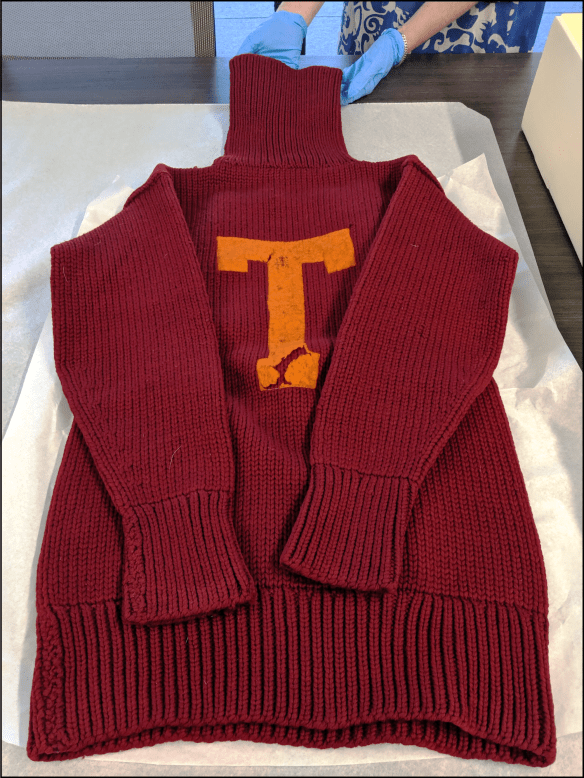

Above: The 1899 football letter sweater earned by halfback Raymond Keller and now preserved in the UT archives, part of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. Photo courtesy of Billy Dale.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

While the uniforms might have been easier to manage, any perception of a common set of University colors was quickly tumbling into chaos. Most (though not all) students were fans the maroon and orange combination, but the alumni were not, and continued to sport orange and white ribbons on their lapels. After all, the colors first made their appearance in 1885, and orange and white ribbons were still used to tie the rolled-up degrees presented at commencement. A few fans were still loyal to old gold and white, colors used by the first football team in 1893 because the campus buildings were uniformly constructed of pale-yellow pressed brick and limestone trim. (The Gebauer Building, just to the east of the Tower, is the last survivor from that era.) To make matters worse, the UT Medical Branch in Galveston was almost unanimous behind a single color: royal blue. (See The Choice of Orange and White)

The issue had ripened to a point where it could no longer be ignored. After much on-campus discussion and a petition by the alumni association to be included in the process, the UT Board of Regents met February 27, 1900 and called for general vote of students, faculty, and alumni. Ballots were to be accepted until April 1.

Among those advocating for maroon and orange was senior law student Ed Overshiner. Known on the campus as “Ovey”, he was also the 5-foot 10-inch, 170 pound center for the football team. In a letter to the University Calendar (along with the Ranger, a student newspaper that pre-dated the Texan), Overshiner wrote, “I think the matter of colors ought to be settled once and for all and with as little change as possible.” Orange and white had been found unsuitable, as white was easily stained and was more an “emblem of capitulation than one of victory.” As for blue, Overshiner claimed he would feel “blue enough to see a crowd of our athletes decked in gaudy blue.” Orange and maroon fit the bill and were colors “already dear to the heart of many a contestant on many a hard fought field. . . I believe that we should all unite, oust the white, and stand for the orange and maroon.”

Among those advocating for maroon and orange was senior law student Ed Overshiner. Known on the campus as “Ovey”, he was also the 5-foot 10-inch, 170 pound center for the football team. In a letter to the University Calendar (along with the Ranger, a student newspaper that pre-dated the Texan), Overshiner wrote, “I think the matter of colors ought to be settled once and for all and with as little change as possible.” Orange and white had been found unsuitable, as white was easily stained and was more an “emblem of capitulation than one of victory.” As for blue, Overshiner claimed he would feel “blue enough to see a crowd of our athletes decked in gaudy blue.” Orange and maroon fit the bill and were colors “already dear to the heart of many a contestant on many a hard fought field. . . I believe that we should all unite, oust the white, and stand for the orange and maroon.”

But the alumni were determined to be heard. Voicing his opinion in the Calendar, geology alumnus Robert Brooks argued that orange and white were “so entwined with the history of the Institution that any attempt to change them would do violence to the associations which they recall.” By replacing white with maroon, Brooks claimed the action of the Athletic Council was “more a thoughtless violation of propriety than deliberate disrespect to the colors of the Institution, and those in charge of the purchase of uniforms for coming athletic teams should not weigh a slight preference for colors supposed to be more serviceable against their loyalty to their University.”

But the alumni were determined to be heard. Voicing his opinion in the Calendar, geology alumnus Robert Brooks argued that orange and white were “so entwined with the history of the Institution that any attempt to change them would do violence to the associations which they recall.” By replacing white with maroon, Brooks claimed the action of the Athletic Council was “more a thoughtless violation of propriety than deliberate disrespect to the colors of the Institution, and those in charge of the purchase of uniforms for coming athletic teams should not weigh a slight preference for colors supposed to be more serviceable against their loyalty to their University.”

April 1 arrived, the ballot box was secured and the votes counted. Exactly 1,111 votes had been cast, 554 from the Austin main campus, 148 from the medical school, and 409 from the alumni. Orange and white received 562 votes, and won the majority by seven ballots. Most of the Austin students had predictably supported orange and maroon, which garnered 310 votes, and Galveston was loyal to blue, which received 203 overall. Crimson came in with 10 ballots, crimson and blue 11, and 15 votes were cast for various other colors (including two votes for Irish green and one for “old gold, maroon, and peacock blue.”)

The Board of Regents ratified the decision at their meeting on May 10, 1900, and maroon mania disappeared almost as suddenly as it arrived. Almost 20 years later, in 1917, Texas A&M replaced its traditional red with maroon.

Above: A 1910, 30-inch University of Texas pennant in orange and white.