or, What the Fulmore School gave to B. Hall, and vice versa.

The Fulmore bell safely resides in the courtyard of the school.

It was the final day of November 1911, as a chilly, peaceful, lazy Thanksgiving morning dawned on the University of Texas campus. The only holiday of the fall term, most of the residents of Brackenridge Hall – or B. Hall, as the men’s dorm was called – expected to enjoy some extra sleep. An inexpensive residence hall intended for the “poor boys” of Texas, B. Hall’s inhabitants didn’t possess many luxuries, and that included alarm clocks. For years, in order to wake everyone in time for breakfast and class, a designated bell ringer strode through the hall with a cowbell promptly at 6:45 a.m. every morning. But the University faculty took a dim view of the cowbell, thought it an unworthy instrument to rouse young college scholars, and at the start of the 1911 academic year had electronic chimes installed as a “more dignified method.” While this eliminated the need for the crude cowbell, the musical chimes turned out to be less than effective on slumbering students, who constantly had to pass up on breakfast in order to make it to their 9 a.m. lectures.

Bong! Bong! Bong! Bong! The morning quiet was abruptly interrupted at the usual 6:45 a.m., but not by a sound usually heard in the hall. A fire alarm? Startled residents rose from their beds and hustled outside to investigate. The noise came from the top of the building. As they peered up to the roof, they discovered a 30-inch brass bell, installed in a makeshift belfry in front of the community room on the fourth floor. How it arrived and who delivered it was a mystery, but the dorm’s inmates weren’t about to let such a gift go to waste. After a noontime Thanksgiving Day dinner, which was universally praised as the “best ever served in the hall,” the 120 residents gathered upstairs for a proper bell dedication. Junior law student Teddy Reese, who was also UT’s head yell leader, provided the oratory, described the history of the cowbells used in the past, dwelled on the failure of the electric chimes to serve their purpose, and expressed the “heartfelt and sincere thanks that is in the bosoms of all B. Hallers for the modest and benevolent donor of the bell, whomever it may be.” Katherine Smith, only the second woman to serve as the hall’s steward, officially christened the bell. “There not being any champagne at hand,” reported The Austin Statesman, “the ‘Belle’ christened the ‘bell’ with a bottle of good old Adam’s ale.” The bell was immediately put to use.

Some of the residents of B. Hall in a 1911 group portrait. Hall steward Katherine Smith is standing on the first floor, center, in the white dress.

In a remarkable coincidence, just as the unexpected bell arrived at B. Hall, a similar bell disappeared from the Fulmore School in South Austin. Opened in 1886, the Fulmore School was initially housed in a whitewashed, wooden, one-room structure just off South Congress Avenue. Austin resident Charles Newning presented the school with a bell in the early 1890s. A prized possession, the bell was rung a half hour before classes began every morning, and again as school ended for the day, so that parents knew their children would soon return home. Its familiar peal had been a part of the neighborhood culture for decades.

Early in 1911, the Austin School Board elected to build a new brick building for the Fulmore School, two blocks south of its original location. It was completed over the summer and formally dedicated on November 17, just two weeks before Thanksgiving. A short wooden bell tower, which looked something like a miniature oil rig, was constructed for the old bell, but it hadn’t yet been installed before the bell disappeared.

The Fulmore School in the 1930s. The building was completed in 1911, with a wooden bell tower (and brass bell) to the right.

As news of B. Hall’s good fortune spread to South Austin, the custodian of the Fulmore School began to wonder if the hall’s newly acquired bell, and the school’s missing bell, might just be one and the same. In the middle of the afternoon on Thursday, December 7, while most of the hall’s residents were in class, the custodian ventured to the UT campus and took an unwise risk. He entered B. Hall alone, quietly crept up the stairs to the belfry, and tried to examine the bell, which sported a fresh coat of red paint to disguise its former appearance. But the intruder was soon discovered, the bell rung in alarm, and B. Hallers sprinted from all parts of the campus to defend their home. According to accounts, one resident giving a speech in his law class heard the bell, abruptly stopped talking, and dashed from the classroom with no explanation. An engineering student was in the middle of a calculus problem at the chalkboard when the bell sounded. He muttered an apology to his professor – engineering dean Thomas Taylor – then jumped out of the first floor open window and hurried to the hall. Before the frightened custodian could make his exit, he was surrounded by a vocal mob of B. Hallers and doused repeatedly with so many buckets of cold water that he later remarked he’d had his bath for the week. But while the bell hadn’t been visibly identified, its familiar sound was unmistakable.

A week later, Dr. Harry Benedict, then serving as Dean of the University (what would today be called the “Provost”), received a letter from Arthur McCallum, the Austin school superintendent. “At a meeting of the school board yesterday afternoon,” wrote McCallum, “I was instructed to ask that the Bell which someone took recently from the South Austin school be replaced or put where someone can get the bell without suffering the humiliation of being watered.” McCallum explained that the bell had “summoned the children of that community to school for a long-long time, and I believe that the people of South Austin are more attached to the bell than the boys of B. Hall.” Certainly the custodian missed the bell, as he had been forced to improvise and use a cowbell of his own to call the children to school.

Benedict, himself a UT graduate and a former resident of the dorm, passed the note along to B. Hall steward Katherine Smith.

The fall ended with the bell secure in its B. Hall roost. It continued to be employed through the new year and into a chilly January, which included a rare, mid-month snowstorm. But as time wore on, the novelty of the bell waned, and “some embryonic reformer” began to urge his fellow residents that it was time to return the item to its true owner. As related in the Cactus yearbook, “So well did this Luther preach that ere long he had converted enough to make the project possible.” Since no one was willing to admit to kidnapping the bell, residents had to come up with a creative solution that would preserve B. Hall’s dignity.

On January 31, 1912, a letter was delivered to Superintendent McCallum from the “B Hall Boys.” It read, in part:

“Referring to the deplorable and regrettable loss of a bell from one of your ward schools and feeling deeply, but unresentingly, the insinuating remarks that have been made in regard to, and on account of, a certain melodious and more or less valuable bell which now swings in the B Hall belfry, we, collectively, individually, and separately, have unanimously agreed to heap coals of fire on your august heads (except the bald ones) by presenting free, gratis, and for nothing, and without trouble on your part, the same melodious, magnificent and misappropriated bell above referred to. This bell will be sent at our (or your) earliest convenience to the South Austin school which is suffering from ‘cowbellitis’ as once even B Hall did.”

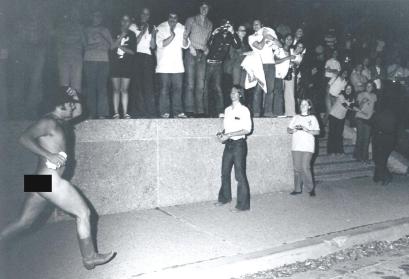

Crossing the new Congress Avenue Bridge, B. Hallers return the Fulmore School bell atop a horse-drawn flat wagon on February 4, 1912.

Clangity-clang! Clangity-clang! The following Saturday afternoon of February 4, amid brief snow flurries, shoppers along Congress Avenue were amused by the ridiculous sight of a horse-drawn flat wagon loaded with about 20 residents of B. Hall, all dressed in various garb. One incessantly rang a bright red bell, and two others, one with a barrel and wooden pole, and other with a tuba, provided musical accompaniment. The sight and noise attracted nearly a hundred local school children, who followed along on foot or rode bicycles. At each street corner downtown, the wagon stopped and yell leader Teddy Reese led the group in “Fifteen Rahs” for the bell. The wagon continued across the bridge, over the Colorado River, and on to South Austin and the Fulmore School, which was three miles south of the University campus. Upon arrival, and with much fanfare, pomp, and ceremony, the bell was presented to the school’s custodian, who graciously accepted the gift.

A century later, the bell still proudly resides at the Fulmore Middle School, minus its coat of red paint.

A few years after the incident (and, perhaps, after a statute of limitations had expired), Teddy Reese confessed to instigating the bell’s capture. In 1910, a new Congress Avenue Bridge was constructed to replace the older, unsteady pontoon bridge that once crossed the Colorado. A year later, the city’s electric trolleys extended a line across the bridge and into South Austin, and UT students began to take their dates on the trolleys to the south side for afternoon walks. The weekend before Thanksgiving, Teddy and his date spied the Fulmore School bell on the ground next to the new building, and Teddy decided that it would make an excellent alternative to the chimes used in the hall. Teddy approached his best friend in the dorm, Walter Hunnicutt (who would later compose “Texas Taps,” better known as the Texas Fight song), and together they recruited a crew of about 10 persons, all sworn to secrecy. In the late night hours before Thanksgiving, the group paid the B. Hall chef to borrow his horse and delivery wagon, went to the Fulmore School, carefully loaded the 300-pound bell so it wouldn’t ring, then returned to campus and quietly hauled the bell upstairs, where it was rung at the break of dawn.

A few years after the incident (and, perhaps, after a statute of limitations had expired), Teddy Reese confessed to instigating the bell’s capture. In 1910, a new Congress Avenue Bridge was constructed to replace the older, unsteady pontoon bridge that once crossed the Colorado. A year later, the city’s electric trolleys extended a line across the bridge and into South Austin, and UT students began to take their dates on the trolleys to the south side for afternoon walks. The weekend before Thanksgiving, Teddy and his date spied the Fulmore School bell on the ground next to the new building, and Teddy decided that it would make an excellent alternative to the chimes used in the hall. Teddy approached his best friend in the dorm, Walter Hunnicutt (who would later compose “Texas Taps,” better known as the Texas Fight song), and together they recruited a crew of about 10 persons, all sworn to secrecy. In the late night hours before Thanksgiving, the group paid the B. Hall chef to borrow his horse and delivery wagon, went to the Fulmore School, carefully loaded the 300-pound bell so it wouldn’t ring, then returned to campus and quietly hauled the bell upstairs, where it was rung at the break of dawn.

Having returned the brass bell, the trusty cowbell was once again heard in B. Hall.

Above: Imposing Mediterranean light fixtures guard the east entrances to Waggener Hall.

Above: Imposing Mediterranean light fixtures guard the east entrances to Waggener Hall.  Above the doorways to the stairwells are signs that indicate Waggener Hall was once designated as a fallout shelter. A common sight on the campus at the height of the Cold War, these 1950s markers are among the very few that haven’t been removed or destroyed, and provide a layer of history to the building. (See “Better Hid than Dead” for a history of UT fallout shelters.)

Above the doorways to the stairwells are signs that indicate Waggener Hall was once designated as a fallout shelter. A common sight on the campus at the height of the Cold War, these 1950s markers are among the very few that haven’t been removed or destroyed, and provide a layer of history to the building. (See “Better Hid than Dead” for a history of UT fallout shelters.) This ornate brass “faculty mail” box is found on the first floor, and is the last of its kind on the campus.

This ornate brass “faculty mail” box is found on the first floor, and is the last of its kind on the campus. Above: Old and new. Waggener Hall was headquarters for the School of Business Administration for three decades until it moved into the Business-Economics Building (today’s Kozmetsky Business Center) in 1962. While Waggener is adorned with Texas products, the colorful ceramic pieces on the current business building are meant to be more abstract. Created by retired UT art professor Paul Hatgil, the rows of small, raised circles were meant to be reminiscent of buttons, as the many inventions of the 1950s had transformed the modern world into what was then called a “push button society.”

Above: Old and new. Waggener Hall was headquarters for the School of Business Administration for three decades until it moved into the Business-Economics Building (today’s Kozmetsky Business Center) in 1962. While Waggener is adorned with Texas products, the colorful ceramic pieces on the current business building are meant to be more abstract. Created by retired UT art professor Paul Hatgil, the rows of small, raised circles were meant to be reminiscent of buttons, as the many inventions of the 1950s had transformed the modern world into what was then called a “push button society.”

Just over a century ago, some enterprising students decided to help themselves to Thanksgiving dinner at the expense of the faculty. In 1912, Charles Francis and a few of his fellow law students were unable to make the trip home for the holidays. Short on cash, they hatched a scheme to “borrow” a turkey that belonged Judge Ira Hildebrand (photo at right), then Dean of the Law School. “Plans and arrangements were perfected and on the night before Thanksgiving, we invaded the coop of Judge Hildebrand and selected one of his best gobblers for a main course.”

Just over a century ago, some enterprising students decided to help themselves to Thanksgiving dinner at the expense of the faculty. In 1912, Charles Francis and a few of his fellow law students were unable to make the trip home for the holidays. Short on cash, they hatched a scheme to “borrow” a turkey that belonged Judge Ira Hildebrand (photo at right), then Dean of the Law School. “Plans and arrangements were perfected and on the night before Thanksgiving, we invaded the coop of Judge Hildebrand and selected one of his best gobblers for a main course.”