Have you heard? The main library at Indiana University is sinking into the ground at the rate of an inch a year. The fault lies with the building’s designer – a graduate from rival Purdue – as he didn’t take into account the extra weight of the books on the shelves. At Iowa State University, any student who carelessly steps on the bronze zodiac inlaid on the floor of the student union building is thereby “cursed” to flunk their next exam. Undergraduates at Princeton warily avoid exiting through the Fitz Randolph Gate at the campus entrance before they graduate. Otherwise, they may never complete their degrees. And at Columbia University in New York, the famous statue of Alma Mater has an owl hidden within the gatherings of her robes. Incoming freshman are told that the first person to find the owl will become the class valedictorian.

Have you heard? The main library at Indiana University is sinking into the ground at the rate of an inch a year. The fault lies with the building’s designer – a graduate from rival Purdue – as he didn’t take into account the extra weight of the books on the shelves. At Iowa State University, any student who carelessly steps on the bronze zodiac inlaid on the floor of the student union building is thereby “cursed” to flunk their next exam. Undergraduates at Princeton warily avoid exiting through the Fitz Randolph Gate at the campus entrance before they graduate. Otherwise, they may never complete their degrees. And at Columbia University in New York, the famous statue of Alma Mater has an owl hidden within the gatherings of her robes. Incoming freshman are told that the first person to find the owl will become the class valedictorian.

Above: The Alma Mater statue at Columbia University. Looking for the owl? Check the robes just behind the left leg.

These are all campus myths, of course. They’re as endemic to college life as all-night study sessions during final exams. The University of Texas has its own collection of myths and lore. Some have been rooted on the campus for decades, while others are relative newcomers to the Forty Acres. Below is a sampling.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

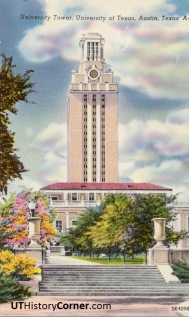

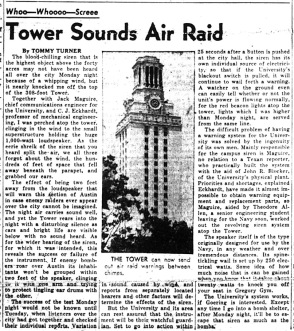

Myth: When viewed from an angle, the UT Tower looks like an owl because it was designed by a Rice University graduate.

This myth is as old as the Main Building. When the top of the Tower is seen diagonally, two of the faces of the clock appear to be a pair of owl’s eyes, while the pointed corner of the observation deck suggests a beak. This is intentional, as the story is told, because the Tower was designed by a graduate of Rice University, whose mascot is the owl. The same myth has been extended to Austin’s Frost Bank Building downtown. Apparently, Rice alumni are very busy.

Actually, the architect of UT’s Main Building and Tower was Paul Cret, who was born in Lyon, France in 1876 and graduated from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then considered the finest place in the world to study architecture. When he was hired as consulting architect by the University in 1930, the 44-year old Cret had immigrated to the United States, was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and had his own private practice with offices in downtown Philadelphia.

Actually, the architect of UT’s Main Building and Tower was Paul Cret, who was born in Lyon, France in 1876 and graduated from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then considered the finest place in the world to study architecture. When he was hired as consulting architect by the University in 1930, the 44-year old Cret had immigrated to the United States, was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and had his own private practice with offices in downtown Philadelphia.

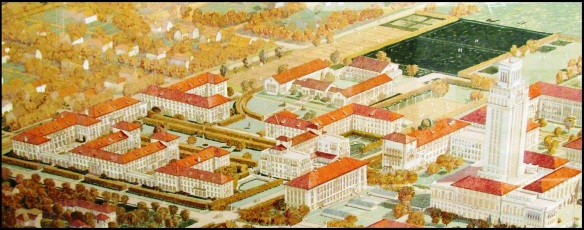

In 1933, Cret completed a campus master plan that influenced the University’s architecture for decades. The South Mall and its “six pack” of buildings, the West Mall guarded by the Texas Union and Goldsmith Hall, the East Mall with the Schoch and Rappaport Buildings, Hogg Auditorium, Mary Gearing Hall, and Painter Hall are all among the products of Cret’s directions.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Myth: The Perry-Castaneda Library was designed in the shape of Texas.

Myth: The Perry-Castaneda Library was designed in the shape of Texas.

University librarians were fielding questions about the shape of the Perry-Castaneda Library well before it opened in 1977. The PCL – informally known as the “PiCkLe” – was planned by the San Antonio architecture firm Bartlett, Cocke and Associates, Inc. and proactively designed to ease the pedestrian traffic around it. Instead of a traditional square or rectangular footprint, corners were trimmed to allow for diagonal pathways in front and behind the building. Other parts were extended to make the best use of available area. The end result was actually meant to better resemble a pinwheel, not the Lone Star State. The Board of Regents approved the plans in March 1974, along with $17 million for construction. (For more about the PCL, see: Forty Years on Forty Acres.)

University librarians were fielding questions about the shape of the Perry-Castaneda Library well before it opened in 1977. The PCL – informally known as the “PiCkLe” – was planned by the San Antonio architecture firm Bartlett, Cocke and Associates, Inc. and proactively designed to ease the pedestrian traffic around it. Instead of a traditional square or rectangular footprint, corners were trimmed to allow for diagonal pathways in front and behind the building. Other parts were extended to make the best use of available area. The end result was actually meant to better resemble a pinwheel, not the Lone Star State. The Board of Regents approved the plans in March 1974, along with $17 million for construction. (For more about the PCL, see: Forty Years on Forty Acres.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Myth: The campus purposely has no North Mall as a Southern snub to the “Yankees.”

This is one of several North vs. South-themed myths which have pervaded the Forty Acres for decades. Another one claims that George Littlefield, the original owner of the Littlefield Home and a Confederate Major, donated the original land for the University campus but stipulated that no building be allowed to face north. None of this is accurate.

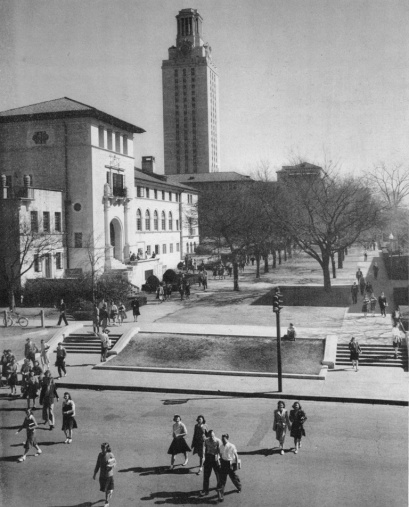

A North Mall was indeed planned for UT, a feature of Paul Cret’s 1933 campus design. Extending north from Mary Gearing Hall, where University Avenue can be found today, the mall was to have been the centerpiece of an intended Women’s Campus and bordered by women’s residence halls, Mary Gearing Hall (then used for the home economics department), and the Anna Hiss Women’s Gym. The mall was to have been longer than its counterpart to the south.

Above: An architectural rendering of the women’s campus north of the Tower, with the Alice Littlefield Dorm for freshmen women at far left and Anna Hiss women’s gym toward upper right. In the center, extending north from Mary Gearing Hall, was the proposed North Mall.

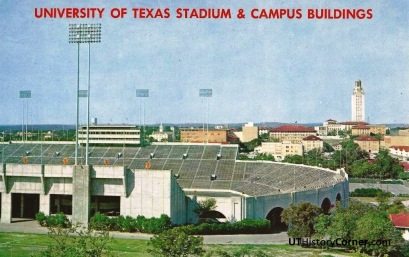

Funding issues delayed the mall during the Great Depression in the 1930s and again when World War II diverted the University’s priorities to the war effort. After the war, the needs of the campus had drastically changed. Returning veterans on the G.I. Bill flooded colleges across the nation; UT’s enrollment more than doubled in just three months, from 6,800 students in June 1946 to more than 17,100 the following September.

The land along University Avenue was needed for other purposes, including a Student Health Center at the corner of University Avenue and Dean Keeton Street (opened in 1950 and since replaced by the Biomedical Engineering Building) and a new facility for the College of Pharmacy, which was sharing an overcrowded Welch Hall with chemistry. With the additional traffic, University Avenue was needed for access and parking, and when the Blanton Residence Hall opened in 1955 on the west side of the street, a grand North Mall no longer seemed feasible.

Above: A 1958 view from the Tower Observation Deck. What was to have been the women’s campus now has a Student Health Center (top right) and a Pharmacy Building on the east side of University Avenue, and the Blanton residence hall to the west. The needed parking prohibited the development of a North Mall.

Why isn’t there a mall on the north side of the Main Building? The reason is a boring, practical one. The Main Building and Tower were completed in 1937 as the new central library, and while malls do extend directly from the building to the east, west, and south, one side needed to be left available for deliveries and emergency vehicles.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Myth: The Board of Regents refused to name the East Mall Fountain, “Peace Fountain.”

As the story goes, when the East Mall and its fountain were completed in 1969, UT students, many of them engaged in anti-Vietnam War protests, asked the Board of Regents to label the new water feature “Peace Fountain.” Allegedly, the regents sarcastically responded by naming it “Pease Fountain” after Elisha Pease, the 1850s Texas Governor who strongly advocated for the founding of the University of Texas. There is some truth here, but only with the first half of the tale.

Completed in May 1969, the East Mall Fountain was an instant hit on the campus, and briefly became something of a mini-Barton Springs. Bathers, waders, and floaters were common in the shallow pools, while others sat along the upper level with legs dangling over the cascade, or lounged and sunned on the grassy expanse of the East Mall. In true Austin style, skinny dippers were occasionally spotted in the fountain late at night.

At 2 p.m. on the sunny afternoon of August 3, 1969, several hundred “hippies, would-be hippies, and clean-cut American kids” gathered at the fountain. Organized by the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, a brief ceremony dubbed the structure “Peace Fountain” before the group took full advantage of the cooling waters on a hot summer day. The event was reported in both The Daily Texan and The Austin American.

At 2 p.m. on the sunny afternoon of August 3, 1969, several hundred “hippies, would-be hippies, and clean-cut American kids” gathered at the fountain. Organized by the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, a brief ceremony dubbed the structure “Peace Fountain” before the group took full advantage of the cooling waters on a hot summer day. The event was reported in both The Daily Texan and The Austin American.

Less than two weeks later, on August 14, the Board of Regents voted to ban all wading and swimming in any of UT’s fountains. There were numerous complaints of trash, including beer bottles, left in an around the East Mall Fountain. The glass covers of the underwater lights had been removed and broken, with the electrical wires torn out, which created a hazardous situation. There were also genuine concerns over someone falling from the fountain’s upper level.

Though wading was prohibited, the unofficial name “Peace Fountain” remained, and the new campus landmark often became a focal point for anti-war activities. When the LBJ Presidential Library was dedicated in May 1971, and with Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon at the ceremony, members of Veterans Against the Vietnam War tossed their military medals and ribbons into the fountain as a protest.

There was never a student request to rename the East Mall Fountain, but “Peace Fountain” was the preferred campus moniker for almost a decade. The Texan regularly used it as late as 1978.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

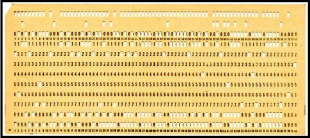

Myth: The window pattern on Burdine Hall resembles a punch-out computer card because the building was supposed to house the computer sciences department.

Certainly, the window pattern on Burdine is unusual, and this kind of thing is ripe for a campus myth, but it’s not true. Burdine Hall was opened in May 1970 for the departments of Government and Sociology. It’s named for John Alton Burdine, a longtime government professor who also served as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (which has since been separated into several colleges and schools).

Certainly, the window pattern on Burdine is unusual, and this kind of thing is ripe for a campus myth, but it’s not true. Burdine Hall was opened in May 1970 for the departments of Government and Sociology. It’s named for John Alton Burdine, a longtime government professor who also served as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (which has since been separated into several colleges and schools).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Myth: Destined to be cut down for a construction project, the Battle Oaks were saved by Professor William Battle when he sat in one of the trees with a shotgun and defied the administration.

Not a chance. In fact, using a shotgun at all would be very much out of character for the bookish Dr. Battle.

A native of North Carolina, Battle was a newly-minted Harvard Ph.D. when he joined the UT faculty in 1893. A professor of Greek and classical studies, he quickly rose through the academic ranks, served as Dean of the University (today called the Provost), and was appointed President ad interim. Along the way, Battle founded the University Co-op through a $2,300 personal loan (his annual salary was $2,500), compiled the first campus directory, and designed the University Seal.

A native of North Carolina, Battle was a newly-minted Harvard Ph.D. when he joined the UT faculty in 1893. A professor of Greek and classical studies, he quickly rose through the academic ranks, served as Dean of the University (today called the Provost), and was appointed President ad interim. Along the way, Battle founded the University Co-op through a $2,300 personal loan (his annual salary was $2,500), compiled the first campus directory, and designed the University Seal.

Perhaps Battle’s greatest contribution to UT was his tenure as chair of the Faculty Building Committee, which oversaw the development of the campus. Battle headed the committee for nearly three decades, from 1920 to 1948, and he took great care to ensure that campus designs and buildings were both appropriate to their setting in Texas and reflected the high aspirations of the University.

Above left: A 1932 photo of Dr. William Battle with a bundle of drawings for the future plans for the campus.

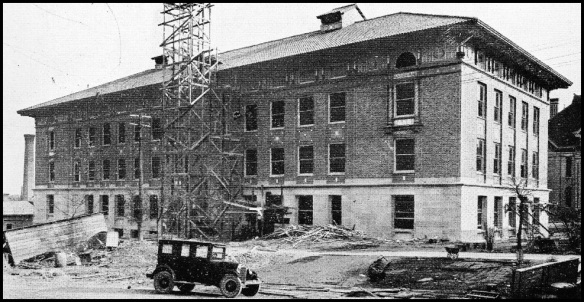

In the early 1920s, plans emerged to build a Biological Labs facility at the southeast corner of Guadalupe and 24th Streets, which would have required the removal of the University’s oldest live oak trees. Students and alumni raised concerns, while a faculty group presented Battle with a formal petition. Battle agreed that the trees should remain, took the matter up with the Board of Regents and convinced them to move the building farther east, where it stands today. The oaks were later named for their champion.

Above: The Biological Labs building under construction. It opened in 1924.

A potential source of this myth can be found in the UT archives. Among those who advocated for preserving the trees was former law professor (and future Board of Regents chair) Robert Batts. In a letter to Battle, Batts passionately wrote that he would “come down to Austin with a shotgun, if necessary” to save the oaks.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Myth: The George Washington statue is on the South Mall because Washington appeared on the Seal of the Confederacy.

A decade ago, there were six additional statues along the South Mall as part of the Littlefield Gateway, and four of them were of persons with direct ties to the Confederacy. It’s understandable that a visitor back then might think the likeness of Washington was connected to the same undertaking. It was centrally positioned, surrounded by the other statues, and was sculpted by the same artist. A closer inspection of the dates and inscriptions, though, shows the Washington statue was a separate project with a very different intent.

A decade ago, there were six additional statues along the South Mall as part of the Littlefield Gateway, and four of them were of persons with direct ties to the Confederacy. It’s understandable that a visitor back then might think the likeness of Washington was connected to the same undertaking. It was centrally positioned, surrounded by the other statues, and was sculpted by the same artist. A closer inspection of the dates and inscriptions, though, shows the Washington statue was a separate project with a very different intent.

The statue of George Washington was the dream of Austin resident Frances Campbell Maxey, an active member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.) and the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, the first historic preservation group in the nation, where Maxey served as the Association’s Texas representative for 36 years. The main visitor gate to Mount Vernon, opened in 1899 as the “Texas Gate,” was built because of Maxey’s fundraising efforts in the Lone Star State.

Maxey read a 1924 newspaper report that claimed Texas was the only state in the Union without a likeness of George Washington. The issue remained with her for years until the D.A.R. began discussions on how to best observe Washington’s 200th birthday in 1932. At Maxey’s suggestion, the D.A.R. asked the University if it might donate a sculpture of Washington for the campus. The UT Board of Regents “heartily” approved of the idea at its September 1930 meeting.

The intent was to have a statue installed by the Washington bicentennial in February 1932, but the Great Depression made fundraising difficult, as well as the Second World War that followed. (The same affected construction of the North Mall as discussed above.) Not until the 1950s was fundraising completed and artist Pompeo Coppini, who’d sculpted the Littlefield Fountain and other South Mall statues, secured for the project. The statue was dedicated in 1955.

The intent was to have a statue installed by the Washington bicentennial in February 1932, but the Great Depression made fundraising difficult, as well as the Second World War that followed. (The same affected construction of the North Mall as discussed above.) Not until the 1950s was fundraising completed and artist Pompeo Coppini, who’d sculpted the Littlefield Fountain and other South Mall statues, secured for the project. The statue was dedicated in 1955.

While a likeness of Washington did appear on the Confederate seal, it wasn’t the motivation behind the statue on the Forty Acres. (For more about the Washington statue, see: How George Washington came to the University of Texas.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Myth: Bevo was named because of the Aggies.

Some myths are stubborn. This legend was debunked more 20 years ago but continues to be told, especially by football fans in College Station.

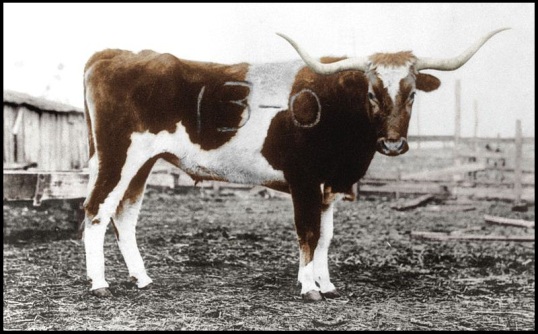

For decades, the claim was that Texas A&M was directly responsible for naming the University’s longhorn mascot “Bevo.” The steer was a gift from UT alumni, presented to students at halftime of the 1916 Texas vs. A&M football game in Austin. The Longhorns went on to win 21 – 7, but several months later, in February 1917, a group of Aggie pranksters snuck into town late at night and branded the steer 13 – 0, the score of the 1915 game in College Station when A&M prevailed. Thus far, this is accurate.

Aggie fans, though, went on to assert that, in order to save face, UT students altered the brand. The “13” was changed into a “B,” the dash into an “E,” a “V” inserted before the “0,” and thus was born the name “Bevo.” This is a myth.

Aggie fans, though, went on to assert that, in order to save face, UT students altered the brand. The “13” was changed into a “B,” the dash into an “E,” a “V” inserted before the “0,” and thus was born the name “Bevo.” This is a myth.

First, there is ample printed evidence soon after the football game that the steer was already known as “Bevo,” both in the Alcalde alumni magazine and in newspapers around the state. One of the articles was dated December 12, 1916 – less than two weeks after the game – and published in the Bryan-College Station Weekly Eagle (left), the hometown newspaper for Texas A&M! This was two months before the steer was branded.

Second, there’s no record that the brand was ever changed. No photo of the mascot with “Bevo” on his side, no mention in any newspaper or any other published source. Some might argue, “well, that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen,” but history requires evidence. Using the same line of thought, we could also claim that Bevo was abducted by space aliens; the lack of supporting proof doesn’t mean it didn’t happen!

Besides, there are several accounts that describe the UT mascot as sporting his original brand. Perhaps the most important is from the Longhorn Magazine, published by UT students. It ran an article about the January 1920 football banquet – in honor of the 1919 team – where the steer, too wild to bring to football games and too expensive to maintain, wound up being the main course for dinner. A delegation from A&M was invited to attend and the history of the mascot was told. The magazine specifically mentioned the original, unaltered brand: “The half of the hide bearing the mystic figures 13 to 0 was presented to A and M with appropriate ceremonies.”

The steer was called “Bevo” months before he was branded and the brand was never changed. (For the story oft he first Bevo mascot, go here.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~