An Extended History of the Littlefield Gateway

It’s been a topic of conversation for most of the summer. Everyone agrees that the University of Texas campus ought to provide a welcoming atmosphere for all members of the UT community, but the statues of Jefferson Davis and other Confederate soldiers along the South Mall, installed in 1933 as part of the Littlefield Memorial Gateway, don’t exactly fit the bill. Some claim this has been a point of contention for the past quarter century, but an extended look at the history of statues and fountain on the South Mall shows that the controversy is as old as the gateway itself.

~~~~~~~~~~

The Littlefield Gateway was the result of an ongoing disagreement between two men whose first and middle names were the same as the country’s first president: George Washington Littlefield and George Washington Brackenridge.

Born in Mississippi in 1842, George Littlefield’s family moved to Texas when he was eight years old. Along with many of his friends, he enlisted in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, rose to the rank of Major, and then returned to Texas to make a fortune in the cattle business, with extensive ranches in West Texas and New Mexico. Littlefield arrived in Austin in the 1880s and organized the American National Bank, which was eventually housed in the Littlefield Building at Sixth Street and Congress Avenue. Late in his life, Littlefield was appointed to the UT Board of Regents and became the University’s greatest benefactor up to that time. Among his many donations are the Alice Littlefield Residence Hall (named for his wife), the Littlefield Fund for Southern History, and the $225,000 purchase of the John Henry Wrenn Library of English literature. With 6,000 volumes dating from 17th century, it was the University’s first rare book collection and brought international attention to the UT libraries.

Born in Mississippi in 1842, George Littlefield’s family moved to Texas when he was eight years old. Along with many of his friends, he enlisted in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, rose to the rank of Major, and then returned to Texas to make a fortune in the cattle business, with extensive ranches in West Texas and New Mexico. Littlefield arrived in Austin in the 1880s and organized the American National Bank, which was eventually housed in the Littlefield Building at Sixth Street and Congress Avenue. Late in his life, Littlefield was appointed to the UT Board of Regents and became the University’s greatest benefactor up to that time. Among his many donations are the Alice Littlefield Residence Hall (named for his wife), the Littlefield Fund for Southern History, and the $225,000 purchase of the John Henry Wrenn Library of English literature. With 6,000 volumes dating from 17th century, it was the University’s first rare book collection and brought international attention to the UT libraries.

In contrast, George Brackenridge was born and raised in Indiana. His father, John, was a local attorney who befriended a young Abraham Lincoln before his family moved to Illinois. Lincoln watched the elder Mr. Brackenridge argue cases in court, occasionally borrowed books from him, and later credited Brackenridge as helping to inspire Lincoln to pursue the law as a profession. George Brackenridge attended Harvard University and moved to Texas with his family when he was 21 years old. During the Civil War, Brackenridge was both pro-Union and war profiteer, shipping cotton through Brownsville and around the Union blockade along the Gulf Coast to New York. After the war, he moved to San Antonio and founded a bank of his own.

In contrast, George Brackenridge was born and raised in Indiana. His father, John, was a local attorney who befriended a young Abraham Lincoln before his family moved to Illinois. Lincoln watched the elder Mr. Brackenridge argue cases in court, occasionally borrowed books from him, and later credited Brackenridge as helping to inspire Lincoln to pursue the law as a profession. George Brackenridge attended Harvard University and moved to Texas with his family when he was 21 years old. During the Civil War, Brackenridge was both pro-Union and war profiteer, shipping cotton through Brownsville and around the Union blockade along the Gulf Coast to New York. After the war, he moved to San Antonio and founded a bank of his own.

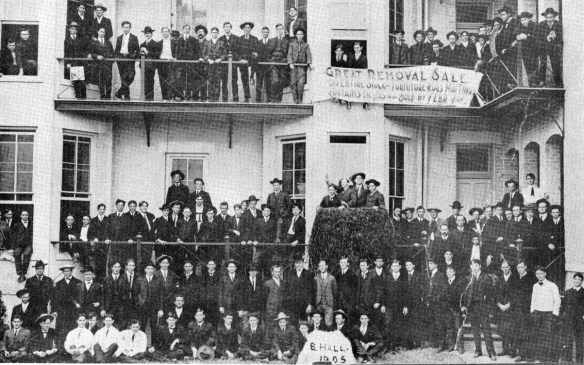

Brackenridge was appointed early to the UT Board of Regents, served for a record 27 years, and was also an important benefactor. Among his donations: the original Brackenridge Hall (better known as old “B. Hall” – photo at left), an inexpensive residence hall for the “poor boys” of the state; University Hall in Galveston as a dorm for women studying medicine; financial backing for a new School of Domestic Economy (today’s School of Human Ecology); and the Brackenridge Loan Fund for women studying architecture, law, and medicine. Early in the University’s history when funds were scarce, the Board of Regents was ready to sell the two million acres of arid West Texas land granted to it by the state legislature and create an endowment. Brackenridge convinced the regents to wait and had the lands properly surveyed at his expense, a decision for which the University was later very grateful.

Brackenridge was appointed early to the UT Board of Regents, served for a record 27 years, and was also an important benefactor. Among his donations: the original Brackenridge Hall (better known as old “B. Hall” – photo at left), an inexpensive residence hall for the “poor boys” of the state; University Hall in Galveston as a dorm for women studying medicine; financial backing for a new School of Domestic Economy (today’s School of Human Ecology); and the Brackenridge Loan Fund for women studying architecture, law, and medicine. Early in the University’s history when funds were scarce, the Board of Regents was ready to sell the two million acres of arid West Texas land granted to it by the state legislature and create an endowment. Brackenridge convinced the regents to wait and had the lands properly surveyed at his expense, a decision for which the University was later very grateful.

Because of their differing views during the Civil War, neither man held the other in high regard. According to UT President Robert Vinson, “Their dislike of each other was profound. When Mr. Brackenridge spoke of the University of Texas, he emphasized the word University. Major Littlefield emphasized the word Texas.” While the two held different ideologies, the animosity may have been exaggerated. In 1917, when Governor James Ferguson vetoed the state appropriation in an attempt to close the University, both Littlefield and Brackenridge pledged to personally underwrite UT’s operating expenses, if necessary. When Littlefield purchased the magnificent Wrenn Library, Brackenridge donated several thousand dollars to publish a catalog for the collection.

~~~~~~~~~~

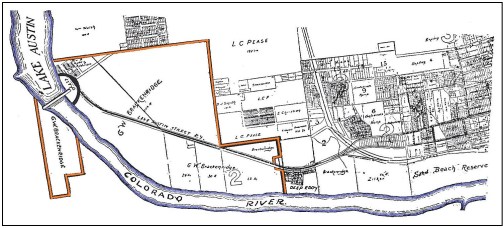

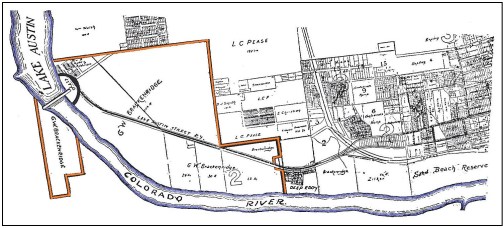

In the early 1900s, UT’s enrollment surpassed 1,000 students and was steadily increasing. Brackenridge realized the University would eventually outgrow its 40-acre campus, and in 1910 donated 500 acres of land to the University along the Colorado River at what is today Lake Austin Boulevard, Married Student Housing, and the Austin Municipal Golf course. He had hoped to purchase up to an additional 1,000 acres and eventually move the University to the 1,500-acre site, where it would have room to grow for generations.

Above: The Brackenridge Tract (outlined in orange), about two miles west of downtown. Map from the Austin American. Color added by the author. Click image for a larger view.

The idea was generally popular with Austinites, but Littlefield, whose mansion was across the street from the Forty Acres, wasn’t eager to see the University relocate to a “Brackenridge campus,” and took measures to keep the location fixed and add additional land instead.

The need of a larger campus resurfaced soon after the conclusion of World War I in November 1918, as thousands of American veterans returned from the trenches in Europe to fill universities across the country. With enrollment in Austin approaching 4,000 students, relocating the University to larger quarters was again being discussed.

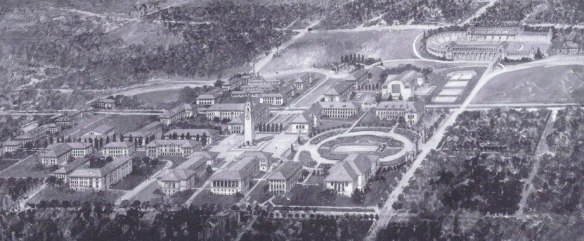

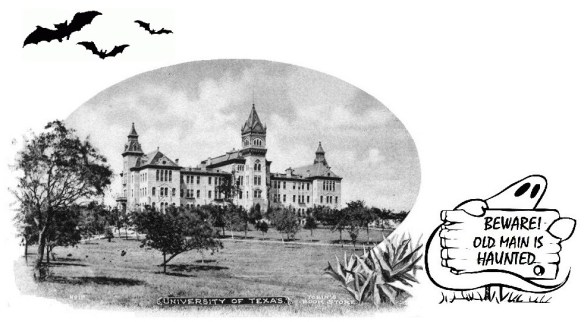

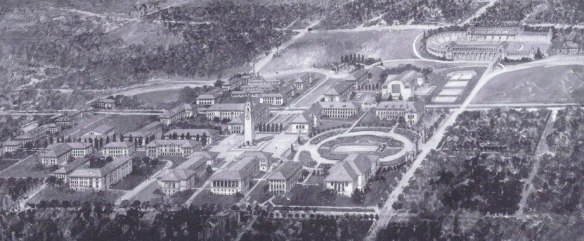

Above: This bird’s eye view of the UT campus from 1908 shows a single-lane road that entered from the south, circled past the Victorian-Gothic old Main Building, and then exited at the same location. The entry point was the site George Littlefield chose to develop into a formal gateway.

To prevent a potential move to the Brackenridge Tract, Littlefield contacted Pompeo Coppini, an Italian-born sculptor then living in Chicago. Coppini, whose friends called him “Pep,” had already worked with Littlefield on the Terry’s Texas Rangers monument on the Texas Capitol grounds. For years, Littlefield had mulled over putting something at the south entrance to the campus. There was yet no formal entryway, just a single-lane graveled road that led up to the old Main Building and wound its way back to the same point. An unremarkable sign that read “Drive to the Right” marked the entrance to the campus.

In 1916, Littlefield had proposed the idea of a “massive bronze arch” to designate the entrance, on which would be statues of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Albert Johnston, John Reagan, and former Texas Governor Jim Hogg. Littlefield, as a product of his time, had long been concerned that the University was becoming too “northernized” and that future generations of UT students might not remember their Southern heritage. The idea of such a monument was not an uncommon one. In the 1990s, concerns were raised that the U.S. had no memorial to its veterans who fought in the Second World War. The need to create one before those who had participated passed on provided a sense of urgency. Within a decade, the National World war II Memorial had been installed in Washington. Similar concerns were voiced in the early part of the 20th century over the Civil War as the ranks of the war’s survivors dwindled. Through the 1920s, a surge of monuments to both the Union and Confederacy appeared in the eastern half of the United States.

Littlefield planned to spend $200,000 (about $4.5 million today) on his gateway. Coppini responded that an arch as the Major envisioned would cost twice that amount, and there the project languished until just after the First World War in 1919.

~~~~~~~~~~

“I want to build that arch,” wrote George Littlefield to Pompeo Coppini (right) on July 23, 1919, “of which you and I talked over some time ago.” This time, though, it wasn’t just just to enshrine Southern history. Littlefield hoped that by placing a formal gateway on campus, it would help to “nail it down.” Coppini complained that the project was still too costly, but Littlefield was willing to try a stone arch instead of bronze, and sent University president Robert Vinson to Chicago to confer with the sculptor. Coppini believed the cost of the monument might drop to $300,000, still over Littlefield’s budget, but Vinson asked Coppini to go ahead with drawings and plans.

“I want to build that arch,” wrote George Littlefield to Pompeo Coppini (right) on July 23, 1919, “of which you and I talked over some time ago.” This time, though, it wasn’t just just to enshrine Southern history. Littlefield hoped that by placing a formal gateway on campus, it would help to “nail it down.” Coppini complained that the project was still too costly, but Littlefield was willing to try a stone arch instead of bronze, and sent University president Robert Vinson to Chicago to confer with the sculptor. Coppini believed the cost of the monument might drop to $300,000, still over Littlefield’s budget, but Vinson asked Coppini to go ahead with drawings and plans.

By early September, plans for the arch were ready and a set of drawings sent to President Vinson in Austin. “If you find that the Major is well pleased with our studies,” Coppini instructed, “just wire at my expense: ‘Go ahead with the plaster model plan’ and I will immediately.” Littlefield, though, was not well. He spent the autumn and much of the winter at the Arlington Hotel in Hot Springs, Arkansas under the care of a team of physicians and nurses, and rarely rose from bed. Vinson notified Coppini of the situation, and the sculptor elected to press ahead with the model.

Above: Recently discovered front and side views of the clay model of Coppini’s “arch” at the Chicago exhibit in April 1920. Click on an image for a larger view. Source: Coppini-Tauch Papers, Box 3R180, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Coppini’s initial design might best be described as an arch in disguise. Though Littlefield had requested it, Coppini strongly objected to the use of arches as memorials, as they were “reminiscent of the Roman Caesarian age,” when empires were “bent on conquering and enslaving other people and reminding them of their yoke, by making them pass under arches in their pompous marches of triumph.” Instead of a portal, Coppini’s arch better resembled a large, free-standing classical niche, constructed from limestone, approximately 40-feet tall, closed at the back and used as the focus of a central display.

Within the niche, Coppini placed three 11-foot statues which stood shoulder-to-shoulder. Most of the notes and plans for the arch have been lost, but a pair of recently discovered images of the clay model shows the central figure was a woman, with her right arm raised and holding a torch. She is an allegorical figure, possibly meant to represent the spirit of the South. On her left, dressed in a double-buttoned Confederate military uniform, was a portrait statue of Robert E. Lee. The person to her right is unclear, but was probably Jefferson Davis. (Click on an image for a closer view.)

Within the niche, Coppini placed three 11-foot statues which stood shoulder-to-shoulder. Most of the notes and plans for the arch have been lost, but a pair of recently discovered images of the clay model shows the central figure was a woman, with her right arm raised and holding a torch. She is an allegorical figure, possibly meant to represent the spirit of the South. On her left, dressed in a double-buttoned Confederate military uniform, was a portrait statue of Robert E. Lee. The person to her right is unclear, but was probably Jefferson Davis. (Click on an image for a closer view.)

Two life-size portrait statues were placed in front of the arch supports, and another pair at the ends of two extended, curved benches that flanked the arch. These were likely Wilson, Hogg, Johnston, and Reagan, though their exact placement is unclear. In front of the arch was a cascade fountain that emptied to a small pool. Two prominent, vertical spouts of water rose from the pool to frame the central group.

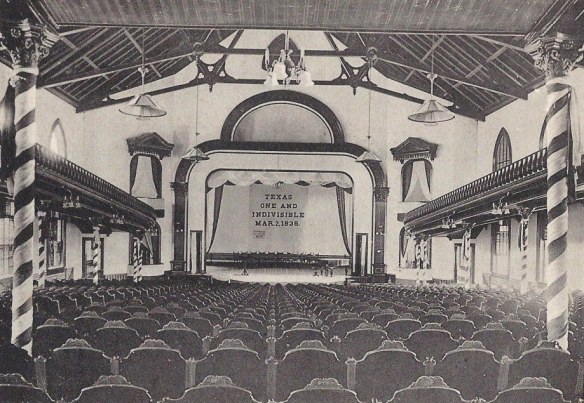

On top of the structure was red-tile roof, added both to further mask the arch as an imitation from ancient Rome and to better harmonize it with the new architectural style of the campus. A decade before, in 1909, the Board of Regents hired Cass Gilbert from New York as the first University Architect. By 1919, Gilbert had designed a library and an education building – today’s Battle (photo at left) and Sutton Halls – as part of an overall campus master plan which brought a new, Mediterranean Renaissance look to the Forty Acres.

On top of the structure was red-tile roof, added both to further mask the arch as an imitation from ancient Rome and to better harmonize it with the new architectural style of the campus. A decade before, in 1909, the Board of Regents hired Cass Gilbert from New York as the first University Architect. By 1919, Gilbert had designed a library and an education building – today’s Battle (photo at left) and Sutton Halls – as part of an overall campus master plan which brought a new, Mediterranean Renaissance look to the Forty Acres.

Above: Coppini and his architects may also have been inspired by the Camp Randall arch in Madison, Wisconsin, just 150 miles northwest of Chicago. Dedicated in 1912, the Camp Randall arch marked the location where 700,000 Union soldiers received their training. It is still an entryway to today’s Camp Randall Stadium at the University of Wisconsin.

Above: Coppini and his architects may also have been inspired by the Camp Randall arch in Madison, Wisconsin, just 150 miles northwest of Chicago. Dedicated in 1912, the Camp Randall arch marked the location where 700,000 Union soldiers received their training. It is still an entryway to today’s Camp Randall Stadium at the University of Wisconsin.

Above: Another way to imagine Coppini’s “arch” is to look at the bellfry on the University United Methodist Church at the corner of 24th and Guadalupe Streets. Though the proportions aren’t quite right, the building materials are similar. Designed in 1908 by architect Frederick Mann, the Spanish Colonial style of the church inspired the UT president and Board of Regents, who thought it was an appropriate look for Texas, to follow a similar style for the campus.

A few days before Christmas 1919, Littlefield was at last well enough to dictate a letter to Coppini. Littlefield hadn’t seen the drawings for the arch, he explained, but understood from others in Austin that the cost was far above his initial limit of $200,000. He was willing to go a little higher. “Now $250,000 is all I want to put into this work, completed,” Littlefield told Coppini, and asked the sculptor to try again.

Coppini responded enthusiastically on December 26th. “I will get to work on a new plan … so I can submit it to you when you get back to Austin.” He also cautioned Littlefield, “We must give up the Arch idea, as it would be a sin to sacrifice any sum of money for something that could not be a credit to you or to me. We want to give something that will express a high ideal and an elevated sense of knowledge and true patriotism, rather than a pile of stones.” The process of designing the arch had given Coppini time to reflect on what Littlefield’s memorial gateway would mean to the University in the future, and had given him the idea for a new concept. Though the model would never be seen in Austin, it was on display the following spring at an architectural exhibition hosted by the Chicago Art Institute.

~~~~~~~~~~

Four months later, on April 15, 1920, Coppini, Littlefield, President Vinson, and other UT officials gathered in Austin to formally discuss the Littlefield Memorial Gateway. Coppini had prepared a new, less expensive design, and replaced the arch with an elaborate fountain. While, per Littlefield’s wishes, the subjects of the portrait statues remained the same, Coppini attempted to recast the gateway as a war memorial.

He explained to Littlefield:

“As time goes by, they will look to the Civil War as a blot on the pages of American history, and the Littlefield Memorial will be resented as keeping up the hatred between the Northern and Southern states.”

Instead, Coppini proposed to honor those who had fought in the World War, as “all past regional differences have disappeared and we are now one welded nation.” Coppini then presented his revised plan for the Littlefield Gateway.

Above: Coppini’s 1920 redesign for the Littlefield Memorial Gateway.

Coppini’s intent was to show the reunification of America in World War I after it had been divided in the Civil War. The scheme centered on a 100-foot long rectangular pool of water. At its head, in an elevated pool to create a cascade, was the bow of a ship, on which stood Columbia, symbol of the American spirit. Behind her to each side stood a member of the Army and the Navy, collectively representing the U.S. armed forces. The ship was to be pulled by three sea horses. As Coppini saw it, the fountain group showed a strong, united America sailing across the ocean to protect democracy abroad.

Immediately behind the fountain, Coppini planned two large pylons or obelisks (37 feet tall), symbolic of the North and the South. In front of each he placed the statues of two “war presidents”: Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy at a time when the country was deeply divided, and Woodrow Wilson, leader of a reunified America during the world war. While these two persons were part of Littlefield’s initial arch, Coppini had transformed them into symbols to compliment the message of the fountain group, not to honor the men individually. The remaining statues of Lee, Reagan, Johnston, and Hogg were staged on either side of the fountain, as a peripheral “court of honor” though less important to the central scheme.

Immediately behind the fountain, Coppini planned two large pylons or obelisks (37 feet tall), symbolic of the North and the South. In front of each he placed the statues of two “war presidents”: Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy at a time when the country was deeply divided, and Woodrow Wilson, leader of a reunified America during the world war. While these two persons were part of Littlefield’s initial arch, Coppini had transformed them into symbols to compliment the message of the fountain group, not to honor the men individually. The remaining statues of Lee, Reagan, Johnston, and Hogg were staged on either side of the fountain, as a peripheral “court of honor” though less important to the central scheme.

While much of the gateway had a new focus, it was, in a sense, a double memorial, attempting to satisfy both Littlefield’s desires to remember Southern history and Coppini’s wish to honor those who had participated in the recent world war. This made the project a difficult one.

Littlefield agreed to the idea, but Coppini later wrote of the meeting:

“We had people unfriendly to us from the very beginning, and many of the faculty were opposed from the start to a Confederate Memorial on the University Campus. That opposition was freely spoken of to me even at the time we exhibited the studies of the first plans, and if it had not been my advice to the Major to let me combine a World War Memorial with the rest of the men he wanted to commemorate, the University, with all probability would not have the Memorial erected on the grounds. Dr. Vinson at the time helped me in converting the Major.”

A contract was written and signed on April 20th and designated a seven-year completion time. A Board of Trustees, composed of the University president, a UT alumnus, and Gus Wroe, the newly elected chairman of the board of Littlefield’s American National Bank (and who had married Littlefield’s niece) would oversee the project and manage the fund. The $250,000 gift was to be divided, half for the production of the statues and pay Coppini as the sculptor, and the remainder for the construction of the gateway.

~~~~~~~~~~

The following September, Vinson made a special trip to New York to confer with architect Cass Gilbert. The two discussed the Littlefield Gateway and what impact it would have on Gilbert’s overall campus scheme, but the UT president was also laying plans of his own.

Vinson was acutely aware that the University of Texas had before it a rare opportunity. Cass Gilbert (photo at left) was among the most eminent architects of his time. The Woolworth Tower in New York, designed by Gilbert, was the tallest building in the world when it opened in 1913. Gilbert had extensive planning experience, having won a competition to design the University of Minnesota shortly before the Board of Regents asked him to come to Austin. His two UT buildings, now Battle and Sutton Halls, had quickly become favorites on the Forty Acres.

Vinson was acutely aware that the University of Texas had before it a rare opportunity. Cass Gilbert (photo at left) was among the most eminent architects of his time. The Woolworth Tower in New York, designed by Gilbert, was the tallest building in the world when it opened in 1913. Gilbert had extensive planning experience, having won a competition to design the University of Minnesota shortly before the Board of Regents asked him to come to Austin. His two UT buildings, now Battle and Sutton Halls, had quickly become favorites on the Forty Acres.

Vinson also had an unused 500-acre tract of land on which he could let his distinguished architect design a truly remarkable campus, and, he believed, the financial assistance of George Brackenridge. Moving the University to new surroundings would be difficult and expensive, and persons like George Littlefield much preferred to simply add additional land to the original acreage. Though Vinson wanted to move, a larger campus in central Austin was also a win in the president’s view, but the window of opportunity was closing. Despite Gilbert’s reputation, there was growing political pressure within the state for the University to hire a Texan as its architect. The Board of Regents might soon be forced to replace Gilbert, and Vinson had decided to force the location issue, either to move or expand the original campus, when the Texas Legislature reconvened in January 1921.

Vinson was careful not to divulge too much, and spoke to Gilbert only about expanding the existing campus. Gilbert considered what impact the Littlefield Memorial would have on the view of the old Main Building on the hill. The proposed 37-foot pylons would certainly hide any low structure. Prophetically, Gilbert began to sketch a new Main Building with a tower.

~~~~~~~~~~~

In the final months of 1920, Littlefield’s health continued to deteriorate until he died peacefully in his sleep on November 10th at 78 years of age. Two days later, the University honored its greatest benefactor as Littlefield’s body lay in state in the vestibule of what today is Battle Hall. (Photo at left.) For several hours, thousands from the University community visited to pay their final respects. A formal burial was held at the Oakwood Cemetery.

In the final months of 1920, Littlefield’s health continued to deteriorate until he died peacefully in his sleep on November 10th at 78 years of age. Two days later, the University honored its greatest benefactor as Littlefield’s body lay in state in the vestibule of what today is Battle Hall. (Photo at left.) For several hours, thousands from the University community visited to pay their final respects. A formal burial was held at the Oakwood Cemetery.

The Major, though, had anticipated what Brackenridge might do, and left nothing to chance. Littlefield’s will included $500,000 toward the construction of a new Main Building, $300,000 and land for a women’s dormitory (now the Alice Littlefield Residence Hall), and $250,000 for the gateway, but all of the gifts were contingent upon the University campus staying where it was for the next eight years. Just hours before he died, Littlefield made one final donation: his turreted Victorian mansion at 24th Street would be turned over to the University subject to Mrs. Littlefield’s life interest, potentially as a home for future UT presidents.

The Major, though, had anticipated what Brackenridge might do, and left nothing to chance. Littlefield’s will included $500,000 toward the construction of a new Main Building, $300,000 and land for a women’s dormitory (now the Alice Littlefield Residence Hall), and $250,000 for the gateway, but all of the gifts were contingent upon the University campus staying where it was for the next eight years. Just hours before he died, Littlefield made one final donation: his turreted Victorian mansion at 24th Street would be turned over to the University subject to Mrs. Littlefield’s life interest, potentially as a home for future UT presidents.

With Littlefield’s passing, Vinson waited only about a month before shifting course. Convinced the University would receive a large bequest from Brackenridge, Vinson called for a Board of Regents meeting to be held on January 5, 1921 in San Antonio with Brackenridge present. The board intended to publicly announce its support to move the University campus. Brackenridge summoned Vinson to San Antonio on December 15th, and the two discussed at length changes to the Brackenridge will, though Vinson never saw the updated document. As late as December 21st, Vinson alerted Cass Gilbert that “our plans for changing the site of the University campus are rapidly maturing.”

And then, on December 28th, George Washington Brackenridge, just a few weeks from his 89th birthday, died.

~~~~~~~~~~

Despite the turn of events, Vinson pressed ahead with the dream of moving the University to a larger, riverfront campus. The regents met in Austin on January 5th and authored an extensive report. It outlined reasons why the University needed more room, argued that a move to the Brackenridge Tract would be more economical in the long term, and asked for approval by the governor and Texas Legislature.

The following day, The Austin Statesman announced “University Gets Brackenridge Fortune” as its top headline. Specifically timed to garner public support for moving the campus, the article claimed an unconditional bequest of more than $3 million was expected, more than enough to counter the Littlefield bequests that would be forfeited if UT left the Forty Acres. Though the Brackenridge will had not yet been filed for probate and made public, the Statesman claimed the information was from “authoritative sources.”

Almost 4,000 UT students met en masse on campus and overwhelmingly approved a resolution in favor of relocation. A series of editorials in The Daily Texan extolled the serious benefits of the roomier Brackenridge Tract , though the students couldn’t resist putting a lighter face on the issue. Cartoons appeared in the Texan and other publications that imagined life on the new campus as a non-stop pool party. Students would jump out of classroom windows for a swim in the Colorado River, and fraternities would live in “frat-boats” on the water.

Almost 4,000 UT students met en masse on campus and overwhelmingly approved a resolution in favor of relocation. A series of editorials in The Daily Texan extolled the serious benefits of the roomier Brackenridge Tract , though the students couldn’t resist putting a lighter face on the issue. Cartoons appeared in the Texan and other publications that imagined life on the new campus as a non-stop pool party. Students would jump out of classroom windows for a swim in the Colorado River, and fraternities would live in “frat-boats” on the water.

Above: Student cartoons portrayed the easy life once the University moved to the Brackenridge Tract. Click on an image for a larger view.

A week after the Austin Statesman headline, Brackenridge’s will became public and it did not mention the University as a beneficiary. Though two courts later ruled that Brackenridge had indeed written a new will, he either had second thoughts and destroyed it, or it was otherwise lost. Either way, Brackenridge’s fortune had waned in his final years to about $1.5 million, barely enough to counter Littlefield’s bequest, and something which Brackenridge apparently didn’t disclose to Vinson. The University president took the news hard, but as the campaign to move the campus had been planned and was already underway, Vison decided to “go straight ahead” and see it through.

In mid-January, a bill to relocate the University was submitted to the Texas Legislature and received solid support from outgoing Governor William Hobby, prominent UT alumni, and the local press. But when the dream of a windfall from the Brackenridge estate didn’t appear, a serious opposition developed. Businesses, churches, and boarding houses near the campus, whose customers or congregations were mostly from the University community, would be seriously affected. As the Brackenridge Tract was still outside the commercial and residential development of Austin, moving the campus to a relatively isolated location would require the additional costs of residence and dining halls. And the forfeiture of Littlefield’s generous bequest had to be considered.

In mid-January, a bill to relocate the University was submitted to the Texas Legislature and received solid support from outgoing Governor William Hobby, prominent UT alumni, and the local press. But when the dream of a windfall from the Brackenridge estate didn’t appear, a serious opposition developed. Businesses, churches, and boarding houses near the campus, whose customers or congregations were mostly from the University community, would be seriously affected. As the Brackenridge Tract was still outside the commercial and residential development of Austin, moving the campus to a relatively isolated location would require the additional costs of residence and dining halls. And the forfeiture of Littlefield’s generous bequest had to be considered.

After the will was read and debate began, some legislators saw an opportunity. If the campus needed more room, why did it have to remain in Austin? One proposal would have allowed any city that could guarantee 500 acres and $10 million to be placed on a ballot, and a statewide election to decide the location.

After the will was read and debate began, some legislators saw an opportunity. If the campus needed more room, why did it have to remain in Austin? One proposal would have allowed any city that could guarantee 500 acres and $10 million to be placed on a ballot, and a statewide election to decide the location.

Once the possibility of losing the University became known, Austin citizens quickly united against the whole idea, and Vinson (photo at right) was harshly criticized for opening a Pandora’s box. The bill to relocate the campus was defeated. An appropriation of $1.35 million was approved to purchase land east of the Forty Acres and extend the campus north to 26th Street and east to present day Robert Dedman Drive. Texas Governor Pat Neff signed the bill April 1st. The next day, President Vinson suspended classes for two hours for a student parade to the Capitol to thank the governor.

Above: ‘Thank you, Governor Pat!” On Saturday, April 2, 1921, students and faculty gathered in front of the Texas Capitol to personally thank Governor Neff for signing the bill that provided additional lands for the campus.

~~~~~~~~~~

While the question of moving the campus was being resolved in Austin, Pompeo Coppini had returned to his Chicago studio to begin work on the gateway. He had hoped to start with the 9-foot Jefferson Davis and Woodrow Wilson statues, as they were of a larger scale than the others, but as this was to be the first ever bronze likeness of Wilson, Coppini wanted to acquire some head shots of the president, as well as borrow a suit and shoes to be certain of the correct proportions. On Coppini’s behalf, Vinson contacted Albert Burleson. A member of UT’s first graduating class in 1884, Burleson had been a U.S. Congressman from Texas for 14 years before being appointed Postmaster General by President Wilson. Vinson sent along copies of the plans for the Littlefield Gateway and asked if Burleson would approach Wilson about the project. President Wilson, though, was less than enthused. While he didn’t formally ask that the statue of him be omitted, Wilson declined to loan one of his suits or send measurements, and reportedly resented the idea of his image standing next to one of Jefferson Davis. (“Possibly because they had so much in common,” wrote Coppini.) Instead, the sculptor saved the Wilson statue for last and relied on published photographs of the president.

While the question of moving the campus was being resolved in Austin, Pompeo Coppini had returned to his Chicago studio to begin work on the gateway. He had hoped to start with the 9-foot Jefferson Davis and Woodrow Wilson statues, as they were of a larger scale than the others, but as this was to be the first ever bronze likeness of Wilson, Coppini wanted to acquire some head shots of the president, as well as borrow a suit and shoes to be certain of the correct proportions. On Coppini’s behalf, Vinson contacted Albert Burleson. A member of UT’s first graduating class in 1884, Burleson had been a U.S. Congressman from Texas for 14 years before being appointed Postmaster General by President Wilson. Vinson sent along copies of the plans for the Littlefield Gateway and asked if Burleson would approach Wilson about the project. President Wilson, though, was less than enthused. While he didn’t formally ask that the statue of him be omitted, Wilson declined to loan one of his suits or send measurements, and reportedly resented the idea of his image standing next to one of Jefferson Davis. (“Possibly because they had so much in common,” wrote Coppini.) Instead, the sculptor saved the Wilson statue for last and relied on published photographs of the president.

In 1922, with his reputation as a first class artist continuing to grow, Coppini moved from Chicago to New York City, where he opened a studio at 210 West 14th Street in the present day Greenwich Village District of Manhattan. Locally, The Brooklyn Sunday Eagle published a multi-page feature on the Littlefield Gateway, called the memorial “remarkable and strikingly symbolic” and quoted Coppini, “Though I am Italian born, I am American reborn.” The New York Times regularly followed the progress of the gateway and Coppini’s other projects, which in turn, made the completion of each statue a brief news item that occasionally was picked up nationally. As Coppini finished a plaster model, it was sent to the Roman Bronze Works in New York, considered to be the best foundry in the United Sates. By the spring of 1925, the six portrait statues were ready and shipped to Austin, where they were placed on display in the Texas Capitol rotunda.

In 1922, with his reputation as a first class artist continuing to grow, Coppini moved from Chicago to New York City, where he opened a studio at 210 West 14th Street in the present day Greenwich Village District of Manhattan. Locally, The Brooklyn Sunday Eagle published a multi-page feature on the Littlefield Gateway, called the memorial “remarkable and strikingly symbolic” and quoted Coppini, “Though I am Italian born, I am American reborn.” The New York Times regularly followed the progress of the gateway and Coppini’s other projects, which in turn, made the completion of each statue a brief news item that occasionally was picked up nationally. As Coppini finished a plaster model, it was sent to the Roman Bronze Works in New York, considered to be the best foundry in the United Sates. By the spring of 1925, the six portrait statues were ready and shipped to Austin, where they were placed on display in the Texas Capitol rotunda.

Photos: Above, Coppini poses with a model of the central fountain group. Below, Coppini and his student, Waldine Tauch, work on the statue of Robert E. Lee in the New York studio.

~~~~~~~~~~

Back in Austin, the 1920s was an eventful decade for the UT campus. By 1922, the Board of Regents had reluctantly released Cass Gilbert as University Architect, citing political pressures to hire a Texas firm. Herbert Greene from Dallas was selected. Robert Vinson resigned as UT’s president in 1923 to oversee Case-Western Reserve University in Cleveland; the search for his successor sparked a controversy that almost derailed the ambitious plans to build the football stadium in 1924. Nine months after Vinson’s departure, oil was discovered on the University lands in West Texas that George Brackenridge had so carefully preserved and surveyed, bringing with it the promise of a much grander building program.

Herbert Greene quickly proved himself an able architect, but while his UT buildings – Garrison (photo at left) and Waggener Halls, the Biological Laboratories, among others – were generally praised, Greene lacked experience in campus planning. Professor John White, from the University of Illinois, was hired as consulting architect. Over several years, White produced a series of campus master plans, none of which completely satisfied the Board of Regents. Sometimes White included the Littlefield Gateway, sometimes not, or he arbitrarily redesigned the memorial without any prior notice to Pompeo Coppini, which prompted a series of angry letters from the sculptor. Ultimately, Coppini refused to work with either Greene or White, and demanded that his original architects, Morison and Walker of Chicago, remain in charge of the gateway.

Herbert Greene quickly proved himself an able architect, but while his UT buildings – Garrison (photo at left) and Waggener Halls, the Biological Laboratories, among others – were generally praised, Greene lacked experience in campus planning. Professor John White, from the University of Illinois, was hired as consulting architect. Over several years, White produced a series of campus master plans, none of which completely satisfied the Board of Regents. Sometimes White included the Littlefield Gateway, sometimes not, or he arbitrarily redesigned the memorial without any prior notice to Pompeo Coppini, which prompted a series of angry letters from the sculptor. Ultimately, Coppini refused to work with either Greene or White, and demanded that his original architects, Morison and Walker of Chicago, remain in charge of the gateway.

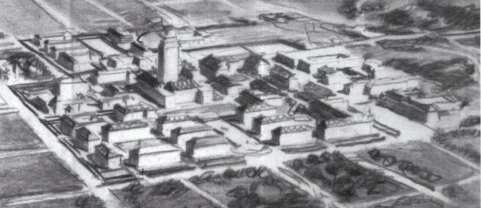

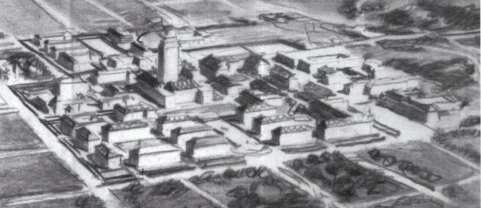

Above and left: A bird’s-eye sketch of one of John White’s campus master plans. Here, the old Main Building has been replaced by a large plaza with a bell tower. While the position of each statue is unclear, Coppini’s entry fountain has become an extended reflecting pool in the center of a circular “South Mall,” though it ignores the grade of the hill. The two obelisks of the gateway, which were supposed to be behind the fountain, have evolved into tall pillars that frame the south entrance to campus. Click on an image for a larger view.

Above and left: A bird’s-eye sketch of one of John White’s campus master plans. Here, the old Main Building has been replaced by a large plaza with a bell tower. While the position of each statue is unclear, Coppini’s entry fountain has become an extended reflecting pool in the center of a circular “South Mall,” though it ignores the grade of the hill. The two obelisks of the gateway, which were supposed to be behind the fountain, have evolved into tall pillars that frame the south entrance to campus. Click on an image for a larger view.

~~~~~~~~~~

Not all of Coppini’s experiences with the University were challenging ones. In the spring of 1928, the 15-foot tall rendering of the winged Columbia – the centerpiece of the fountain and focus of the entire gateway – was finished. To celebrate, the New York chapter of the UT alumni association, which called itself The Texas Club, organized an open house at Coppini’s studio for Sunday afternoon, May 6th. Tea was served, music was provided by UT alumni Katherine Rose and Guy Pitner, and more than 400 guests wandered through Coppini’s studio to admire his many works, but especially his latest creation.

Not all of Coppini’s experiences with the University were challenging ones. In the spring of 1928, the 15-foot tall rendering of the winged Columbia – the centerpiece of the fountain and focus of the entire gateway – was finished. To celebrate, the New York chapter of the UT alumni association, which called itself The Texas Club, organized an open house at Coppini’s studio for Sunday afternoon, May 6th. Tea was served, music was provided by UT alumni Katherine Rose and Guy Pitner, and more than 400 guests wandered through Coppini’s studio to admire his many works, but especially his latest creation.

The statue of Columbia, as the sculptor’s symbol of a reunited America in the Great War, appealed to a wide audience. A reporter from the Associated Press attended the open house, and then sent a brief article with photographs over the news wires. That the University of Texas was about to install a patriotic war memorial, gifted by former Confederate soldier George Littlefield and sculpted by Pompeo Coppini, was a story printed by newspapers along both coasts and in dozens of towns and cities in between. International Newsreel also attended the event. At a time before television, 7 – 10 minute black and white newsreels were a staple in movie theaters nationwide, usually shown just before the feature film. Coppini and the Columbia statue (along with a mention of the University) were highlighted in a newsreel in early summer.

~~~~~~~~~~

Above: The University of Texas campus in the late 1920s. The single lane road that curves around to the front of Old Main is still present.

By 1929, with all of the statuary completed, it seemed that the time had finally arrived to install the Littlefield Gateway. “The largest and costliest monumental group on any American university campus has been completed, and the memorial will be set in place this year,” announced the Austin Statesman on April 28th. But as construction estimates began to arrive, Coppini’s longtime fears were soon realized. The prices for building materials had increased over the decade, and the total cost would exceed the $125,000 limit of Littlefield’s bequest.

Over the summer, Morison and Walker reviewed the gateway designs and substituted less expensive granite for some of the limestone pieces. The Board of Trustees took stronger measures. Over Coppini’s protests, the board voted to eliminate the costly 37-foot obelisks from the memorial. UT President Harry Benedict had long been concerned that the pylons would block the view of the old Main Building, while Coppini passionately argued that removing them would destroy intended symbolism. To remain within the budget, however, the trustees opted to cut the obelisks. The gateway now only needed a green light from the Board of Regents to begin construction.

Approval was expected when the Board of Regents met in Austin on Friday, November 8th, and Gus Wroe, chair of the Board of Trustees, was invited to attend the meeting. But the group fell into an extended discussion about the history of the gateway and its size relative to nearby buildings. To everyone’s surprise, Wroe suggested that if the memorial was too large for the south entrance, it could be moved to the east side of campus. President Benedict, as a second trustee, and who still thought the gateway was too large, agreed. With the consent of a majority of the trustees, the regents promptly voted to relocate the entire memorial to the hill northeast of the new football stadium (where the LBJ fountain is today), to serve as the terminus of a planned East Mall that would extend from the Main Building.

Regent Sam Neathery shared the board’s’ views with The Daily Texan: “In changing the location of the memorial, the Board of Regents felt it was too large to fit in with the surroundings afforded by the south entrance location. It is too close to the Main Building.” Neathery then added the underlying core reason, which echoed Coppini’s concerns in 1919:

“The arrangement is out of keeping with the times. The work will keep the antagonism of the South against the North before the people of Texas.”

President Benedict dubbed the gateway a “derelict plane hovering around; no one knows where it is going to land. It approached its landing during the month [of November], but found at the last moment a fresh gust which sent it soaring again.”

News of the regents’ action provoked an immediate response from Alice Littlefield, George Littlefield’s widow, who was still living in the mansion at 24th Street. Mrs. Littlefield was adamant. The original contract specified the gateway would be installed at the south entrance to the campus, and the Board of Regents in 1920 accepted the gift under those conditions. Wroe, who had first suggested the move, likely angered many of his Littlefield relatives, abruptly changed his position, sided with Mrs. Littlefield, and let it be known that if the University refused to place the memorial as intended, it might be gifted to the city of Austin instead.

News of the regents’ action provoked an immediate response from Alice Littlefield, George Littlefield’s widow, who was still living in the mansion at 24th Street. Mrs. Littlefield was adamant. The original contract specified the gateway would be installed at the south entrance to the campus, and the Board of Regents in 1920 accepted the gift under those conditions. Wroe, who had first suggested the move, likely angered many of his Littlefield relatives, abruptly changed his position, sided with Mrs. Littlefield, and let it be known that if the University refused to place the memorial as intended, it might be gifted to the city of Austin instead.

By January 1930, Wroe had convinced Dudley Woodward (the third trustee) that the gateway should remain at the south entrance, even though the Board of Regents had already voted to move it. Wroe also informed Coppini, and intimated that the bronze works might simply be placed on the hillside without the fountain. Coppini was livid. “How could the pool of water be eliminated?” Coppini responded. How would it look to have the prow of the ship “appear to navigate on dry land? The joke is not even funny!” Newspapers nationwide had picked up on the story. Some, which the previous year had run photos of the Columbia statue and praised the patriotic war memorial, now incorrectly reported that the regents had rejected it outright, which created a public relations nightmare for the University; others claimed that Wroe, speaking on behalf of the Littlefield family, had given the regents an “ultimatum.” The gateway would be placed as originally agreed or “not at all,” and either gifted to Austin or the state, where it might be installed at the south entrance to the Capitol grounds.

The regents, though, were already reconsidering their actions. Regent Ed Crane, a Dallas attorney, wrote to President Benedict, “I have concluded that neither you as a Trustee of the Littlefield Gateway Memorial nor the Board of Regents can adhere to the conclusion … that the ‘South Entrance’ designated in the will means the East entrance to the campus.” Crane was rather candid about his view of the gateway: “In spite of all the kicks … that our esthetic senses experienced every time we contemplated the erection of the mosquito pond in our front yard, it was a foregone conclusion that Major Littlefield’s wishes should be followed.” The regent continued, “Much of the future of the University … will be determined by the extent to which donations are received by private sources. “ To move the gateway would be to “broadcast to the world” the University’s willingness to break its promise to the dying wish of a generous donor.

~~~~~~~~~~

At their March 1930 meeting, the regents seemed resigned to the idea that the gateway would need to be positioned at the south entrance, but waited on taking any official action. Instead, the board hired a new consulting architect. The collaboration with John White from Illinois had not worked well, and a national search had led to Paul Cret in Philadelphia (photo at right). Born in Lyon, France, educated at Paris’ Ecole des Beaux Arts (then considered to be the finest architecture academy in the world), Cret had immigrated to the United States and was head of the School of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

At their March 1930 meeting, the regents seemed resigned to the idea that the gateway would need to be positioned at the south entrance, but waited on taking any official action. Instead, the board hired a new consulting architect. The collaboration with John White from Illinois had not worked well, and a national search had led to Paul Cret in Philadelphia (photo at right). Born in Lyon, France, educated at Paris’ Ecole des Beaux Arts (then considered to be the finest architecture academy in the world), Cret had immigrated to the United States and was head of the School of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

Cret met with the regents, expressed his belief that the campus “could be made one of the most beautiful in the country,” and was asked to begin immediately on a preliminary master plan, which included the placing of the Littlefield Gateway. If the memorial had to be at the south entrance, the regents wanted Cret’s opinion on its appearance.

Above: Charcoal sketch of the UT campus master plan by Paul Cret. Click on image for a larger view.Source: University of Texas Buildings Collection, Alexander Architecture Archives, University of Texas Libraries.

Cret’s office worked quickly. When the regents convened again on May 30th, Cret presented the initial draft of a plot plan, a report that argued for the eventual replacement of Old Main with a new library (today’s Main Building and Tower), and had fundamentally revised the Littlefield Gateway, expanding and melding it to be part of a formal South Mall.

“The Littlefield Memorial,” wrote Cret:

“instead of a small composition, overcrowded with features and designed without regard for its surroundings, was expanded so as to form an entrance to the campus. The portrait statuary was separated from the allegorical figures, as the juxtaposition of these two types was objectionable on account of the difference in scale. The portrait statues selected by the donor gain in prominence when provided with an individual setting instead of being used as accessories to a fountain design.”

Cret had placed the portrait statues along the east and west sides of the mall, which kept them from obstructing the view of the Main Building at the top of the hill. At the same time, they were also separated from the fountain group, and any symbolic meaning Coppini had intended was lost.

Both the Faculty Building Committee and the Board of Regents enthusiastically endorsed Cret’s solution. The regents not only approved the idea, but agreed to fund any additional construction costs. In July, Faculty Building Committee chair William Battle and Board of Regents chair Lutcher Stark journeyed to Philadelphia to visit with Cret, while Coppini was asked to join them. Together, they went over the revised plan. Though Coppini was disappointed, he had great respect for Paul Cret and reluctantly agreed to the new scheme.

~~~~~~~~~~

Early the following year, in 1931, a minor new wrinkle appeared, as the Texas chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.) proposed giving an equestrian statue of George Washington to the University. Cret was asked for an opinion on the best place for it and to “think the matter over.” Several sites were proposed, but Cret advocated the statue join the court of honor on the South Mall. Initially, the D.A.R. project was an ambitious one, with a statue of Washington on horseback. But as the Great Depression of the 1930s worsened, fundraising became a challenge, and then was put on hold through World War II. It wasn’t until 1955 that a standing George Washington was unveiled at the head of the South Mall. Fortunately, Pompeo Coppini, though his work on the Littlefield Gateway had finished decades before, agreed to once again be the sculptor, which preserved an important sense of continuity to the statuary on the South Mall.

Above: The bird’s eye view of Paul Cret’s campus master plan for the University of Texas, which was completed in 1933. The new positions of the portrait statues extended the Littlefield Gateway to the length of the mall, effectively making the entire South Mall a campus entrance.

Left: A close-up of the proposed equestrian statue of George Washington, which was initially placed on the Main Mall. Click on the image for an expanded view. Source: University of Texas Buildings Collection, Alexander Architecture Archives, University of Texas Libraries.

Left: A close-up of the proposed equestrian statue of George Washington, which was initially placed on the Main Mall. Click on the image for an expanded view. Source: University of Texas Buildings Collection, Alexander Architecture Archives, University of Texas Libraries.

With Cret’s plan for the South Mall approved by the regents, time was needed for the Morison and Walker firm to once again revise the gateway. There were, of course, inevitable delays: a shallow utility tunnel had to be moved, soil studies were needed before the pump room was dug two stories beneath the fountain, and there were issues with transporting the fountain group – which weighed 18,200 pounds – from New York. (Each wing on the statue of Columbia was 400 pounds of bronze.)

~~~~~~~~~~

On March 2, 1932, Pompeo Coppini returned the courtesy that the New York chapter of UT alumni had shown in 1928 by hosting a Texas Independence Day dinner in his studio (photo above). A packed crowd enjoyed the meal, live music, and the warmth of their happy host. Coppini had every reason to celebrate, as construction on the Littlefield Gateway finally began later the same year and was completed the following spring. The fountain and statues (along with nine new campus buildings) were officially dedicated on Saturday, April 29, 1933 as part of a celebration to mark the University’s 50th anniversary.

Above: Robert L. White as UT’s supervising architect, Pompeo Coppini, and architect Paul Cret (seated) at the Littlefield Gateway for its dedication in April 1933.

Sources:

Archival

Alexander Architecture Archives: University of Texas Buildings Collection

Dolph Briscoe Center for American History: UT President’s Office Papers, Coppini-Tauch Papers, George W. Littlefield Papers, William J. Battle Papers, UT Memorabilia Collection

Chicago Institute of Art: Catalog for Annual Architecture Exhibit: April – May, 1920

University of Pennsylvania Libraries: Paul Cret Papers

Library of Congress: Universal Newsreel Archives

New York Historical Society: Cass Gilbert Papers

Books

Benedict, Harry Y., Source Book of the History of the University of Texas (1917)

Coppini, Pompeo, From Dawn until Sunset (1940)

Long, Walter L., For All Time To Come (1964)

Sibley, Marilyn M., George W. Brackenridge: A Life (1973)

Newspapers/Magazines

Austin Daily Statesman, The Daily Texan, The Dallas Morning News, San Antonio Express-News, The New York Times, Alcalde (UT alumni magazine), Longhorn Magazine (UT student publication)

Special thanks to Dr. David Gracy, Professor Emeritis of the UT School of Information. Dr. Gracy is currently writing what will likely be the definitive biography of George Littlefield, and happily shared some knowledge and insights about the Major.

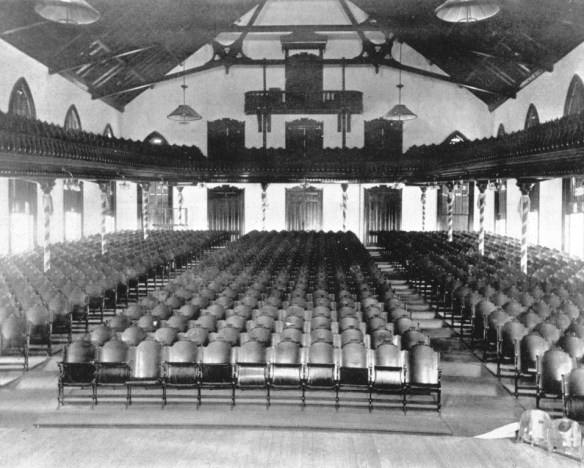

The Main Building with its 27-story Tower was to be the long-term solution to a problem that had plagued the Board of Regents for decades: how to increase the size of the library. The University library was initially housed on the first floor of the old Main Building (Photo at right. Click for a larger view.), but as its holdings increased, the space needed for additional bookshelves literally squeezed the students out of the reading room. The problem was temporarily relieved with the construction of a separate library building in 1911 (now Battle Hall), but by 1920, its quarters were again hopelessly overcrowded. A new library was needed, but where to place it?

The Main Building with its 27-story Tower was to be the long-term solution to a problem that had plagued the Board of Regents for decades: how to increase the size of the library. The University library was initially housed on the first floor of the old Main Building (Photo at right. Click for a larger view.), but as its holdings increased, the space needed for additional bookshelves literally squeezed the students out of the reading room. The problem was temporarily relieved with the construction of a separate library building in 1911 (now Battle Hall), but by 1920, its quarters were again hopelessly overcrowded. A new library was needed, but where to place it? In 1930, the Board of Regents hired Paul Cret as Consulting Architect for the University. Born in in 1876 in Lyon, France, Cret had graduated from the Ecole des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris, at the time considered to be the world’s best university for architecture instruction. He immigrated to the United States early in the 20th century and was the head of the School of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania when he was agreed to take on the consulting position for UT. Cret was to design a new master plan for the campus, and among his first priorities was the solution for a new library.

In 1930, the Board of Regents hired Paul Cret as Consulting Architect for the University. Born in in 1876 in Lyon, France, Cret had graduated from the Ecole des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris, at the time considered to be the world’s best university for architecture instruction. He immigrated to the United States early in the 20th century and was the head of the School of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania when he was agreed to take on the consulting position for UT. Cret was to design a new master plan for the campus, and among his first priorities was the solution for a new library. Two spacious reading rooms were placed on either side of the Catalogue Room. To the east was the Hall of Noble Words. (Photo at left.) The ceiling featured a series of heavy concrete beams painted to look like wood. Each side of a beam was decorated with quotes within a specific theme, among them: friendship, patriotism, freedom, wisdom, and truth. It was hoped that the students studying below would occasionally glance upward and be inspired by the exhortations above them. The Hall of Texas opened to the west. The beams here depicted periods of Texas settlement and history, from the times of Native Americans up to the opening of the University. While the Plant Resources Center takes up part of the Hall of Texas, it and the Hall of Noble Words are still open to the public, used by UT students for almost eight decades.

Two spacious reading rooms were placed on either side of the Catalogue Room. To the east was the Hall of Noble Words. (Photo at left.) The ceiling featured a series of heavy concrete beams painted to look like wood. Each side of a beam was decorated with quotes within a specific theme, among them: friendship, patriotism, freedom, wisdom, and truth. It was hoped that the students studying below would occasionally glance upward and be inspired by the exhortations above them. The Hall of Texas opened to the west. The beams here depicted periods of Texas settlement and history, from the times of Native Americans up to the opening of the University. While the Plant Resources Center takes up part of the Hall of Texas, it and the Hall of Noble Words are still open to the public, used by UT students for almost eight decades.

In the final months of 1920, Littlefield’s health continued to deteriorate until he died peacefully in his sleep on November 10th at 78 years of age. Two days later, the University honored its greatest benefactor as Littlefield’s body lay in state in the vestibule of what today is Battle Hall. (Photo at left.) For several hours, thousands from the University community visited to pay their final respects. A formal burial was held at the Oakwood Cemetery.

In the final months of 1920, Littlefield’s health continued to deteriorate until he died peacefully in his sleep on November 10th at 78 years of age. Two days later, the University honored its greatest benefactor as Littlefield’s body lay in state in the vestibule of what today is Battle Hall. (Photo at left.) For several hours, thousands from the University community visited to pay their final respects. A formal burial was held at the Oakwood Cemetery.