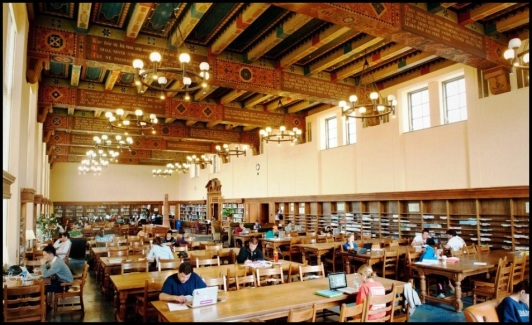

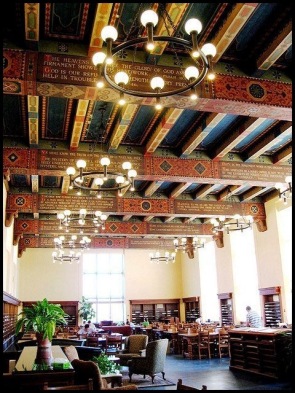

On the University of Texas campus, it’s a place like no other. A room where the ceiling seems almost anxious to speak with visitors, to offer a nugget of wisdom, share a spiritual proverb, or proffer encouraging advice.

Here, over 80 years ago, the University’s faculty and staff came together hoping to inspire the students of their day and future generations.

When you visit, be sure to look up. It’s the best way to appreciate the Hall of Noble Words.

~~~~~~~~~~

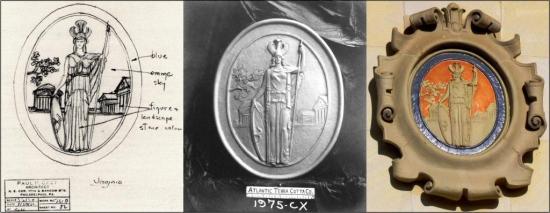

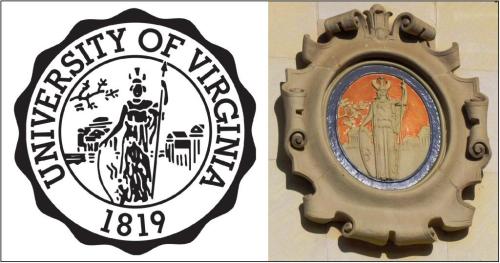

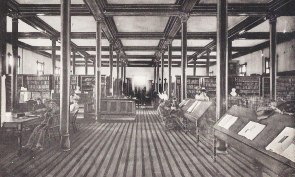

Opened in 1934, the hall was part of the first phase of construction of the Main Building as the new central library (see “How to Build a Tower“) and one of a pair of spacious reading rooms. Embellishing the ceiling with quotations was the brainchild of Dr. William Battle, the chair of the Faculty Building Committee. Battle joined the UT faulty in 1893 as a classics professor, and had served as Dean of the Faculty (what today would be called the provost) and as Acting President. Along the way, he founded the University Co-op and was responsible for the design of UT’s official seal.

Opened in 1934, the hall was part of the first phase of construction of the Main Building as the new central library (see “How to Build a Tower“) and one of a pair of spacious reading rooms. Embellishing the ceiling with quotations was the brainchild of Dr. William Battle, the chair of the Faculty Building Committee. Battle joined the UT faulty in 1893 as a classics professor, and had served as Dean of the Faculty (what today would be called the provost) and as Acting President. Along the way, he founded the University Co-op and was responsible for the design of UT’s official seal.

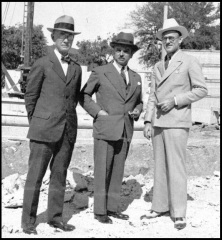

Above left: William Battle (left), poses with UT’s consulting architect Paul Cret (center) and supervising architect Robert White.

With construction of phase one well underway, the Faculty Building Committee met in May 1933 and heartily approved of Battle’s idea for the east reading room, and then compiled a list of possible of citations as a starting point, “to serve as a basis for discussion.” It was hoped that the quotations on the ceiling would provide a source of inspiration for students studying below, who might occasionally glance up during breaks in their studies. The committee, though, wanted input from more of the campus, so that the final result was truly a University-wide effort.

With construction of phase one well underway, the Faculty Building Committee met in May 1933 and heartily approved of Battle’s idea for the east reading room, and then compiled a list of possible of citations as a starting point, “to serve as a basis for discussion.” It was hoped that the quotations on the ceiling would provide a source of inspiration for students studying below, who might occasionally glance up during breaks in their studies. The committee, though, wanted input from more of the campus, so that the final result was truly a University-wide effort.

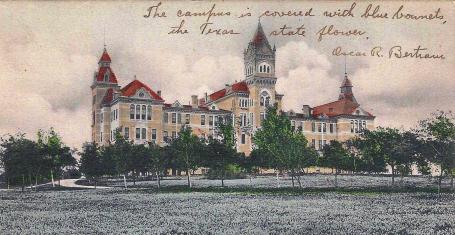

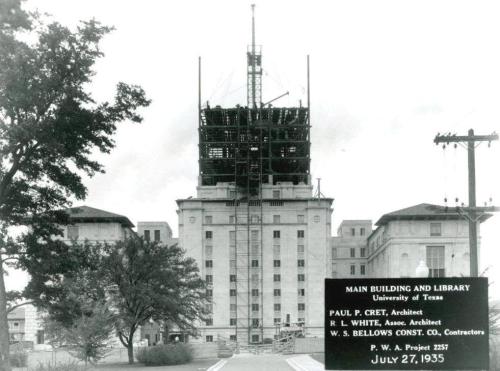

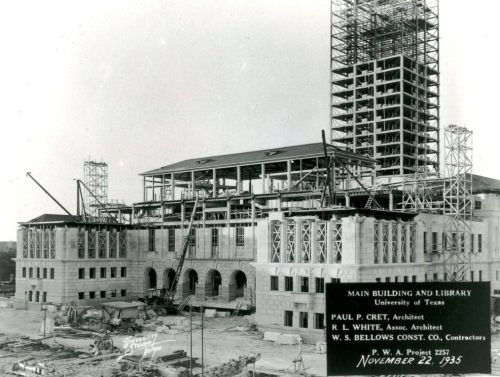

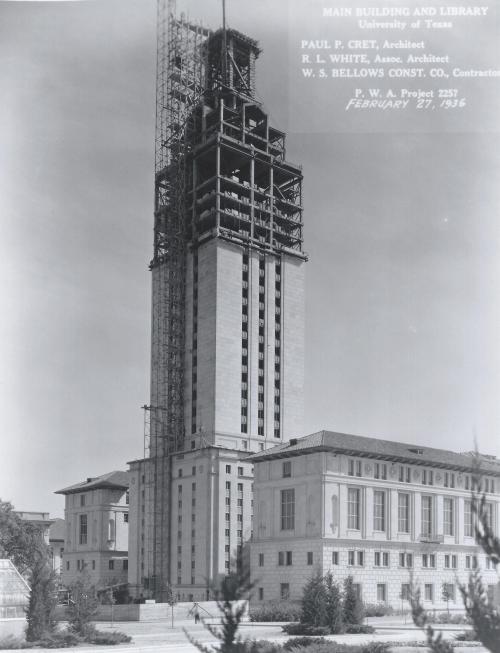

Above right: Construction of phase one of the Main Building and Tower. The future Hall of Noble Words is on the second floor of the east side – the far side in this photograph. Click on an image for a larger view.

In early June 1933, Battle sent mimeographed copies of a letter to selected members of the faculty and staff. “Dear Colleague,” wrote Battle, “As a part of the decoration of the ceiling of the east reading room of the new library, the Building Committee contemplates the use of noble and inspiring utterances appropriate to the function of the room as an educational agency. The concrete beams offer long, broad surfaces well adapted for such a purpose . . . We might, with propriety, call the reading room The Hall of Noble Words.”

“The Committee would be greatly pleased if you would suggest utterances that seem to you appropriate,” Battle continued. “Perhaps the thoughts expressed may occasionally find lodgment in the minds of users of the reading room.”

Battle didn’t have to wait long for submissions, and they arrived from all parts of the campus. “I am much pleased by your suggestion for the use of noble utterances,” wrote accounting and management professor Chester Lay from the College of Business Administration. “I have myself often remembered and pondered such a quotation in the main reading room of the Harper Memorial Library at the University of Chicago:”

“Read not to contradict and confute; nor to believe and take for granted; nor to find talk and discourse; but to weigh and consider.” – Roger Bacon

“I like the idea of using inspiring inscriptions,” responded home economics professor Lucy Rathbone, “The thing that impressed me most in the Library of Congress was the quotations carved on the columns.” Rathbone offered:

“The strength of a man’s virtue is not to be measured by the efforts he makes under pressure but by his ordinary conduct.” – Blaise Pascal

History professor Ed Barker submitted Martin Luther’s “Heir stehe ich. Ich kann nicht anders.” (Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise.) Anthropology professor James Pearce suggested an Issac Barrow quote: “He that loveth a book will never want a faithful friend, a wholesome counselor, a cheerful companion, an effectual comforter.” And Mattie Hatcher, an archivist in the University Library who specialized in the Spanish and Mexican eras of Texas history, provided a regional offering with a quote from Stephen F. Austin: “A nation can only be free, happy, and great in proportion to the virtue and intelligence of the people.” All of the above quotations found their way onto the beams in the reading room.

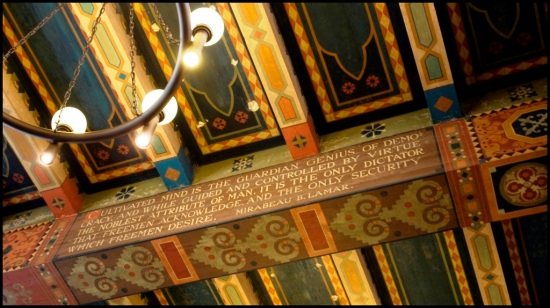

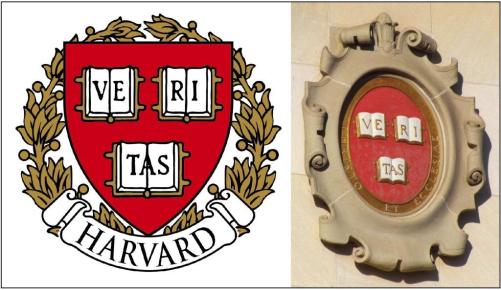

Above: The quote from Republic of Texas President Mirabeau Lamar’s 1838 address, “Cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy,” became the University’s motto and appears in Latin on the official UT seal as Disciplina Praesidium Civitatis, or “Education is the safeguard of democracy.”

Architect Paul Cret also offered his support. “The idea of inscriptions on the beams of the east room is excellent.” He encouraged the use of bright, intricate, and interesting designs to accompany the words, and counseled, “Do not be afraid of having the color scheme too high in key at first. It will become subdued with age – like all of us.”

Of course, Battle received far more suggestions that could be used, and the Faculty Building Committee spent the month of July making difficult choices. The end result, though, was a list that was both varied in content and well-represented across the Forty Acres.

Eugene Gilboe, the celebrated Dallas painter and interior designer, perhaps best-known for his murals in theaters throughout the state, was recruited to paint the ceiling. He used stencils for the letters and freehand for the surrounding designs. On campus, Gilboe was also hired to paint the beams in the Texas Union Presidential Lobby and the ceiling of Hogg Auditorium.

~~~~~~~~~~

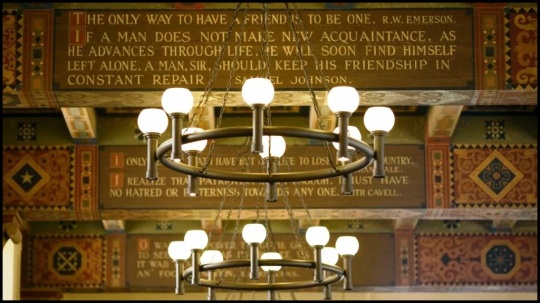

In the Hall of Noble Words, each side of the eight ceiling beams has a designated theme, under which appropriate quotations are grouped. Freedom, education, and wisdom are among the topics, along with friendship, determination, law and mercy, and the value of books. Citations from Shakespeare, Tennyson, Kipling, Aristotle, and the Bible are here, as well as a passage from Alice in Wonderland.

The side of one beam was designated “Appeal of the University of Texas” and displays a single quote from Yancey Lewis, an 1885 UT law graduate (right):

The side of one beam was designated “Appeal of the University of Texas” and displays a single quote from Yancey Lewis, an 1885 UT law graduate (right):

“Let us in this University strike hands with the ancient and goodly fellowship of university men of all time . . . and pledge ourselves, as university men and Texans, to love the truth and seek it, to learn the right and do it, and, in all emergencies, however wealth may tempt or popular applause allure, to be sole rulers of our own free speech, masters of our own untrammeled thoughts, captains of our own unfettered souls.”

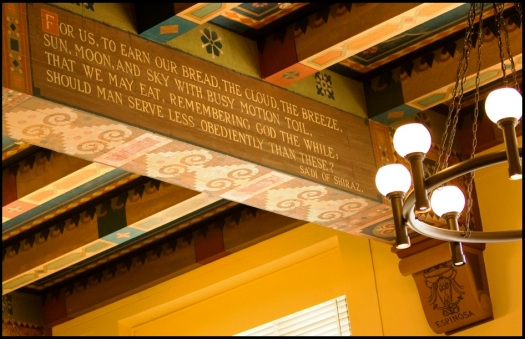

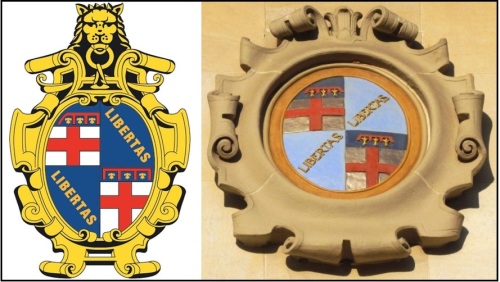

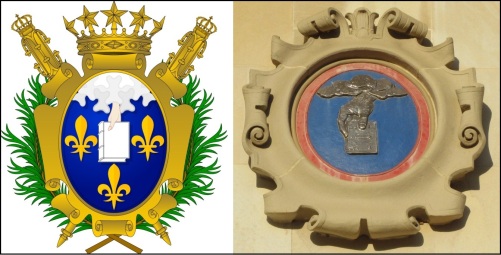

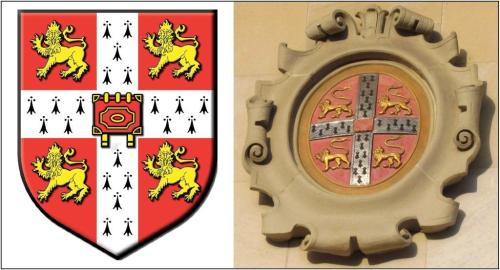

The brackets that support the beams display printers’ marks from the 15th and 16 centuries. Among them is the Aldine Press, founded by Aldus Manutius of Venice, Italy. Known for publishing Greek, Roman, and Italian classics in their original languages, Manutius was famous for his new italic typeface, emulated by his peers across Italy.

The brackets that support the beams display printers’ marks from the 15th and 16 centuries. Among them is the Aldine Press, founded by Aldus Manutius of Venice, Italy. Known for publishing Greek, Roman, and Italian classics in their original languages, Manutius was famous for his new italic typeface, emulated by his peers across Italy.

Aldus’ printer mark (left) displays a swift-moving porpoise wrapped around a ship’s anchor with the cautionary motto “festina lente,” or, “Make haste, slowly.”

Above: A quote from Sa’di of Shiraz (Saadi Shirazi), a distinguished Persian poet and author from the 13th century. To the lower right, the bracket displays the printer mark of Antonio de Espinosa, who immigrated to Mexico City from Spain in 1550 and founded one of the first printing houses in North America. Click on an image for a larger view.

~~~~~~~~~~

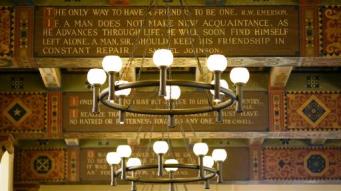

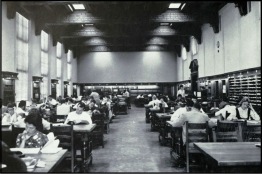

The Hall of Noble Words opened to rave reviews in 1934, though students sometimes complained that the chandeliers didn’t provide enough light in the evenings. In the 1950s, fluorescent lights replaced the original fixtures (photo at right), though the new lights were installed directly on to the painted ceiling. Just over half a century later, in 2007, the room was restored much as it was in the 1930s, with new – and brighter – chandeliers, though the removal of the fluorescent lights left permanent scars.

The Hall of Noble Words opened to rave reviews in 1934, though students sometimes complained that the chandeliers didn’t provide enough light in the evenings. In the 1950s, fluorescent lights replaced the original fixtures (photo at right), though the new lights were installed directly on to the painted ceiling. Just over half a century later, in 2007, the room was restored much as it was in the 1930s, with new – and brighter – chandeliers, though the removal of the fluorescent lights left permanent scars.

Left: The Hall of Noble Words soon after its 2007 restoration. Click on an image for a larger version.

Left: The Hall of Noble Words soon after its 2007 restoration. Click on an image for a larger version.