Careful! Look close, or you might miss it. Take a stroll along the sidewalk, heading north on San Jacinto Boulevard as it approaches the football stadium. The street makes a long, lazy curve as it follows the route of Waller Creek, just to the west. But as you near the stadium, where the creek straightens out for a bit, the road makes a slight veer to the left. The sidewalk that once shadowed the creek’s bank from a polite distance is abruptly pushed over and rudely intrudes out over the embankment, supported by concrete pillars.

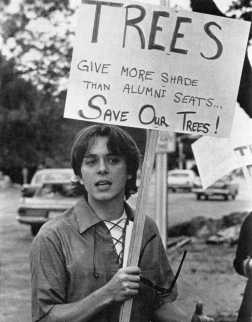

Decades ago, this spot was informally dubbed “Erwin’s Bend,” after Board of Regents chair Frank Erwin, though the name wasn’t intended as a token of admiration. In 1969, this was the site of the “Battle of Waller Creek,” a famed student protest against the removal of trees to make room for a stadium expansion.

The sidewalk along San Jacinto Boulevard is suddenly pushed out over Waller Creek as it nears Bellmont Hall and the stadium, seen on the right.

For University of Texas students in 1969, the world was exciting, troubling, and volatile. Social upheavals, civil rights, the war in Vietnam, and the new ecology movement were all making headlines. Recent student protests at Cal-Berkeley and Harvard had college administrators everywhere on edge. A June fire on the Cuyahoga River near Cleveland, a result of too much chemical pollution, instigated the Clean Water Act and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. The following month, the world watched as humans aboard Apollo 11 explored the surface of the moon. (Its successor, Apollo 12, was due to launch in November with UT graduate Alan Bean on board.) In August, a music festival at Woodstock in upstate New York attracted 400,000 people and became a defining event for a generation.

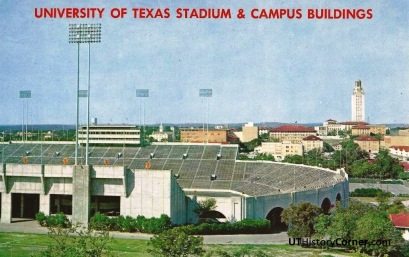

The UT Austin campus was also being transformed. Muscling in next to the familiar Mediterranean buildings with red-tiled roofs were brawny, multi-storied tan brick or concrete structures. Beauford T. Jester Center, named for a former governor and regent, opened in the fall as one of the largest college residence halls anywhere. The Humanities Research Center, the LBJ Presidential Library, and a 17-story physics-math-astronomy building were all being planned, along with a sizeable addition to the football stadium.

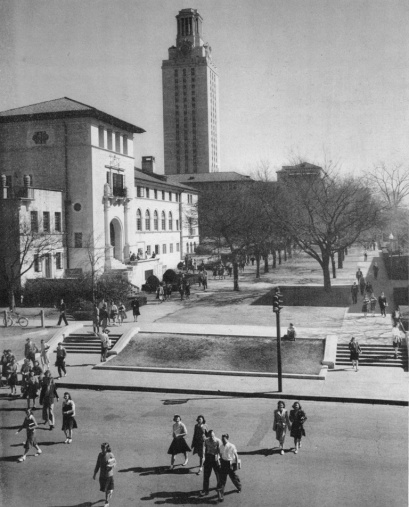

Bellmont Hall, as seen from the UT Tower observation deck, provides the support for second-tier seating on the stadium’s west side.

In May of 1969, the Board of Regents approved final plans for a new building to be placed along the west side of the stadium. Known today as Bellmont Hall and named for Theo Bellmont, UT’s first athletic director, it was both an academic and athletics structure. Designed to house the classrooms and labs of the physical education department (now the Department of Kinesiology), along with the administrative offices of intercollegiate athletics, its roof supported an upper deck to the stadium with seating for 14,000 football fans. The total cost was just over $12 million, though because of its mixed use, about 70% of the financing came from Permanent University Fund bond proceeds, the rest from the sale of seating options in the stadium.

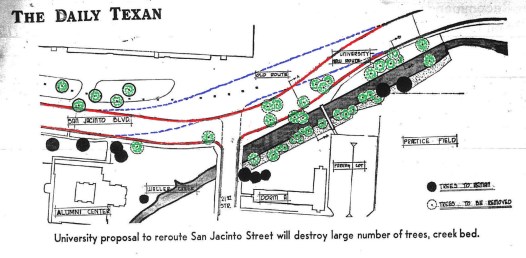

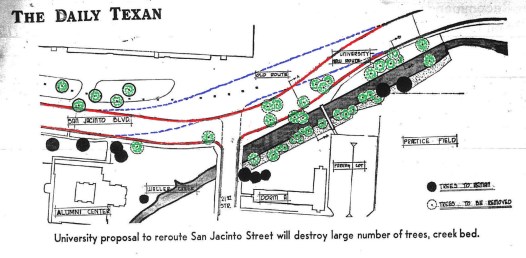

But to make room for the new building, the live oak trees, which had shaded the western gates of the stadium for decades, would have to be removed. The location of San Jacinto Boulevard was also an issue. Its route cut through the south footprint of the structure. Campus planners proposed to move a portion of the street about 65 feet to the west, though it would have consequences for the trees along a section of Waller Creek. All told, 39 trees were slated for destruction, and the bed and banks of the creek destined to be paved for erosion control.

Above: The plan to redirect San Jacinto Boulevard, published in The Daily Texan. (Color is mine.) East is up and north to the left. The stadium, before the addition of Bellmont Hall, is seen in the upper left, with the alumni center across the street. Lower right, Dorm A and the parking lot have since been replaced by the San Jacinto Residence Hall, and the practice field is today’s Clark Field. Blue marks the original route, while red indicates the altered, and current, position of the street. Green circles specify the 39 trees removed. Click on the image for a larger version.

Though the regents had discussed plans to relocate the street for months, it wasn’t common knowledge on campus until an article appeared in The Daily Texan in early October. A contract had been signed and a work order issued to a San Antonio contractor. Construction was to begin before the end of the month. As the full significance of the project and what it meant to Waller Creek was realized, opposition developed, particularly among architecture students who wanted to find an alternative solution.

On Wednesday, October 15th, thousands of UT students joined an estimated half million across the country in what was billed as a “national moratorium” against the war in Vietnam. Protesters gathered on the Main Mall at noon, then marched to the Capitol for a larger rally. “Two bits, four bits, six bits, a dollar. All for peace, stand up and holler!” chanted the crowd. Among the speakers was student body president Joe Krier. “We have the right and duty to integrally question the course of this nation,” Krier was quoted in the Texan. The moratorium made national headlines for days, and the idea of protesting to affect change was in the air.

On Wednesday, October 15th, thousands of UT students joined an estimated half million across the country in what was billed as a “national moratorium” against the war in Vietnam. Protesters gathered on the Main Mall at noon, then marched to the Capitol for a larger rally. “Two bits, four bits, six bits, a dollar. All for peace, stand up and holler!” chanted the crowd. Among the speakers was student body president Joe Krier. “We have the right and duty to integrally question the course of this nation,” Krier was quoted in the Texan. The moratorium made national headlines for days, and the idea of protesting to affect change was in the air.

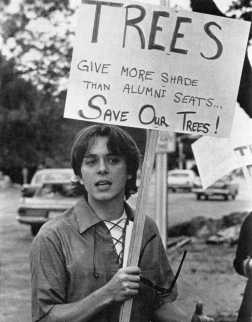

Meanwhile, the fate of Waller Creek was quickly becoming a campus issue. Letters to the editor appeared in the newspaper from students and faculty alike. Some, taking their cue from the ecology movement, were opposed to the destruction of a place of natural beauty and believed the creek was about to become a paved drainage ditch. Others railed against the need for more seats in the stadium. That the top-ranked Longhorn football team was headed towards its second national championship didn’t seem to matter. Architecture students created substitute proposals: a less drastic reroute of San Jacinto, or a narrow street to reduce the impact. A common thread running through the various opinions was the desire to have more public input on future development of the campus.

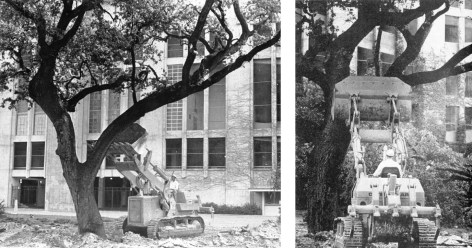

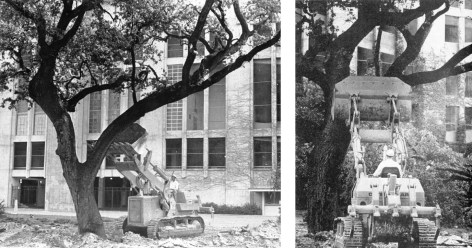

The following Tuesday, October 21st, less than a week after the national moratorium protests, contractors with bulldozers arrived at the stadium and removed the trees along the west side. But when they turned their attention to the creek, more than 50 sign-carrying protesters stood in the way. For the contractors, they needed to complete their task by a deadline or would have to pay a penalty, but rather than provoke a more serious situation, the bulldozers were shut down. Dr. Bryce Jordan, Vice President for Student Affairs, instructed the crews not to resume clearing until they received instructions from the president’s office.

Bulldozers removed the trees next to the stadium on Tuesday, October 21st.

A group of students, many of them architecture majors, asked UT President Norman Hackerman for a one week delay to propose additional alternatives. Late Tuesday afternoon, Hackerman released a statement. He had requested Frank Taniguchi, Dean of the School of Architecture, to recommend four faculty and two students who would form an advisory committee “for the future development and preservation” of Waller Creek. As to the stadium addition, the site had been under study for 18 months, and the president’s office could find “no better alternative in view of the necessary configuration and size of the construction project.”

The architecture dean personally visited with the protesters. “There is no alternative. I think it is too late,” Dr. Taniguchi explained. Because the contracts had been finalized by the Board of Regents, any postponement on the part of the University would result in a financial penalty. The contractors had agreed to finish on time, but the University had guaranteed the work. Some students took President Hackerman’s statement about an advisory group as an encouraging sign, but thought “future development” ought to include the stadium addition. In the meantime, two botany professors and a pair of UT law students partnered with the local Sierra Club and filed for a temporary restraining order to halt construction, though any court order would not be issued until mid-morning on Wednesday.

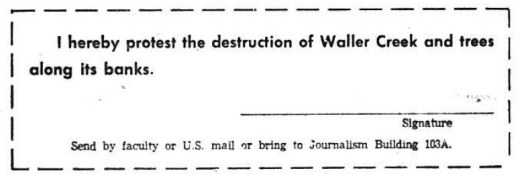

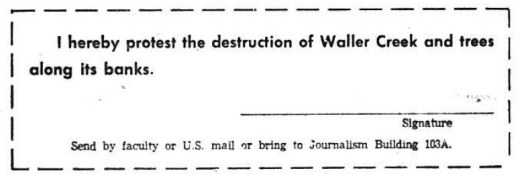

Above: Printed on the editorial page of The Daily Texan, Wednesday, October 22, 1969.

As Wednesday morning dawned, The Daily Texan was full of news about the protest and had printed a petition slip that could be cut out, signed, and delivered to the Texan offices. The slips were to be presented en masse to President Hackerman. But any petition would be too late, as the situation had dramatically changed.

All along the disputed section of Waller Creek, the cedar, live oak, pecan, and maple trees – many of them well over a century old – were full of dozens of students. A few had spent the night, worried that construction crews might return in the dark. The rest arrived at sunrise and climbed the branches in a “tree-in” with the hope that they could delay any action before the expected restraining order was issued.

Into the fray came Frank Erwin, Chairman of the Board of Regents. Born in Waxahachie, a World War II veteran who’d earned a law degree from the University, Erwin made a career in politics working for the state Democratic party. A supporter of the conservative faction, he was appointed spokesman for the Texas delegation to the 1968 National Democratic Convention. A longtime colleague and friend of Texas governor John Connally, Erwin was appointed to the Board of Regents in 1963, and served until 1975. For five years, from 1966-1971, Erwin was chairman.

Into the fray came Frank Erwin, Chairman of the Board of Regents. Born in Waxahachie, a World War II veteran who’d earned a law degree from the University, Erwin made a career in politics working for the state Democratic party. A supporter of the conservative faction, he was appointed spokesman for the Texas delegation to the 1968 National Democratic Convention. A longtime colleague and friend of Texas governor John Connally, Erwin was appointed to the Board of Regents in 1963, and served until 1975. For five years, from 1966-1971, Erwin was chairman.

While politics was important to him, most biographers agree that the University was Erwin’s primary passion for the latter part of his life. Working with his many political allies in the Texas Legislature, he increased university appropriations from $40 million to almost $350 million in just over a decade, and was critical to the formation of the University of Texas System in 1967. At the end of his tenure as regent, Erwin was widely lauded for his contributions to higher education in Texas.

But Erwin was also controversial and often polarizing. With a firm belief in his authority, Erwin tried to mold the University in the image he chose, a tactic which regularly alienated students, faculty, and the administration. Labeled a believer in the Texas mantra “bigger is better,” Erwin was a prime mover behind the new, large-scale campus architecture. He read the news of student unrest at Berkeley, became determined not to let the counterculture movement find a home in Austin, and worked to close the campus to non-students and push out faculty whose views Erwin believed were too liberal and unpatriotic for the times. During his tenure, student government and the Faculty Council both demanded Erwin’s resignation, and his heavy-handed actions prompted several prestigious faculty members to leave for other universities. “Opinion has remained divided as to [Erwin’s] final usefulness to the University,” wrote UT English professor Joseph Jones, “although most fair-minded observers agree that in his own way, on his own terms, he was singularly devoted to it.”

One thing Frank Erwin was not, was patient. While there were reports the UT administration wanted to hold construction until a crisis could be avoided, Erwin arrived in person at Waller Creek early in the morning, surveyed the scene, and, without contacting President Hackerman, called in campus, city, and state law enforcement, along with a fire truck with an extended ladder, to remove the students from the trees as quickly as possible.

“This was the first time anyone had ever used police on this campus on any large scale to suppress dissent,” wrote UT student Larry Grisham, whose account was published in The Harvard Crimson student newspaper. Hundreds had gathered to watch police use ladders and safety nets to bodily remove tenacious protesters from the trees. Erwin was in a hurry to beat the restraining order, and was quoted by the Texan: “Arrest all the people you have to; once the trees are down, there won’t be anything to protest.” Working their way up to higher branches, police found that removing the last few holdouts, using the extended ladder of the fire truck, was a tricky process. “The most amazing part of the morning was that nobody got killed,” recounted Grisham, “They even sawed off one limb with a person still on it.” The final protester was a girl perched on the end of a branch atop of an estimated 50-foot tall cypress tree. “When the police did get to her, they almost knocked her off the branch – she dangled for several minutes by her hands.” In all, 27 people were arrested.

With the protesters dispatched, police formed lines to secure the construction zone as bulldozers and crews set to work to remove the trees. As the first tree fell, Erwin was photographed applauding the effort. The trees were downed in such a hurry that at least one designated to be spared was razed by accident. A restraining order was issued a little before noon, but it was too late.

Waller Creek after the trees have been felled. The lone cypress in the center, next to the 21st Street bridge, still survives. Moore-Hill residence hall is in the upper left.

Grisham expressed what was a popular opinion among those who had witnessed the morning’s events. “Erwin had broken the non-violent tradition on this campus by, for the first time, using force and outside force at that. He had completely ignored the students and faculty and their alternative plans and opinions; he had barely managed to stay inside the law by cutting the trees just before the injunction; and he had no business being on the campus trying to start a riot – if anybody were to urge on the bulldozers, it should have been the university administration.” As was seen in the letters to the editor earlier in the week, the Waller Creek protest wasn’t just about the trees. It was an appeal for a broader voice in the future of the University.

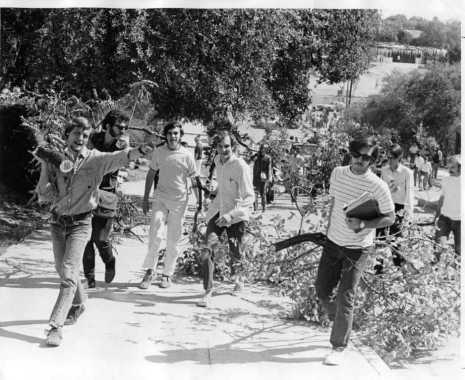

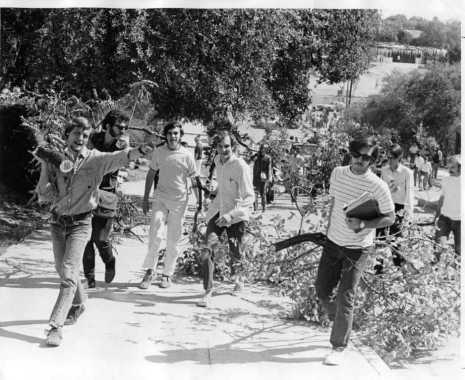

Just before noon, students carry branches up the 21st Street hill to the Main Building.

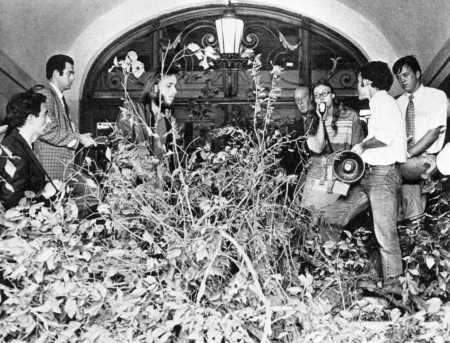

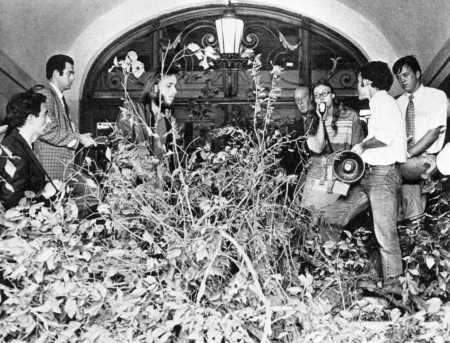

The students, though, were not yet finished. As the construction crews retreated and broke for lunch, several hundred persons grabbed branches, large and small, towed them out of the creek bed, up the 21st Street hill, through the South Mall, and up to the Main Building. As the students approached, administrators feared the worst and locked the doors as the branches were piled in the entryways. A rally on the Main Mall followed, and President Hackerman agreed to meet with a small delegation. Hackerman did what he could to ease the situation, and arranged for students to meet with Erwin the following day. The University’s campus planning office announced that no more trees would be removed, and, as a concession to the students’ demands, the bed of Waller Creek would not be paved as originally proposed.

Branches were stuffed into the entrances of the Main Building.

By Thursday, the “Battle of Waller Creek” was front page news across the state, covered from Los Angeles to New York, and images of students being forcibly removed from trees were published in newspapers as far away as Paris, France. Its effect was long lasting. Today, treasured live oaks on the campus are considered investments and relocated, rather than destroyed, when they sit in the path of campus construction. Waller Creek is also viewed as an asset, and efforts are underway, both on campus and through downtown Austin, to preserve the creek and take advantage of it architecturally. And building development is now primarily guided by a holistic campus master plan, with input from all corners of the University.

It’s the season! While the week after Thanksgiving is fraught with due dates for research papers, a last round of tests, and with final exams looming, the campus still finds ways to get in the holiday spirit. A Texas-sized, eight-foot Menorah is placed on the West Mall to celebrate Hanukkah, enormous Christmas trees grace the lobbies of the Texas Union and Student Acitivity Center, and strings of lights, wreaths, and other decorations are scattered throughout the campus. (The “book tree” at left was found in the Perry-Castaneda Library.

It’s the season! While the week after Thanksgiving is fraught with due dates for research papers, a last round of tests, and with final exams looming, the campus still finds ways to get in the holiday spirit. A Texas-sized, eight-foot Menorah is placed on the West Mall to celebrate Hanukkah, enormous Christmas trees grace the lobbies of the Texas Union and Student Acitivity Center, and strings of lights, wreaths, and other decorations are scattered throughout the campus. (The “book tree” at left was found in the Perry-Castaneda Library.