A century ago, the University went all out to celebrate William Shakespeare.

Above: UT students portray characters from The Winters Tale for a campus-wide Shakespeare pageant.

Forsooth! This year marks the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare. For the occasion, the University’s Harry Ransom Center presented a special exhibit of its extensive Shakespeare collection, including three copies of the 1623 First Folio (left), considered by many to be the most important collection of English literature ever published.

Forsooth! This year marks the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare. For the occasion, the University’s Harry Ransom Center presented a special exhibit of its extensive Shakespeare collection, including three copies of the 1623 First Folio (left), considered by many to be the most important collection of English literature ever published.

On the anniversary date – Saturday, April 23rd – the UT campus was relatively quiet. There were no ceremonies to honor William Shakespeare. No speeches, parades, songs, dances, revels, or plays performed to remember the Bard from Stratford. That might sound a little over the top, but a century ago, the entire University community turned the 300th anniversary, the Shakespeare Tercentenary, into a five day Shakespeare-palooza.

~~~~~~~~~~

Mention Shakespeare and the University of Texas in the same sentence and the conversation inevitably turns to the Shakespeare at Winedale program. Begun in 1970 as a summer class by English professor James Ayers on the premise that the best way to explore Shakespeare’s plays is to perform them, the program has grown into a year-round effort that reaches students from elementary school through college. Most performances still take place in a now iconic nineteenth-century barn at the Winedale Historical Complex east of Austin, in the tiny town of Round Top. Though it’s an unlikely setting, both students and audiences alike swelter through the Texas summer heat to immerse themselves in Shakespeare’s works.

Mention Shakespeare and the University of Texas in the same sentence and the conversation inevitably turns to the Shakespeare at Winedale program. Begun in 1970 as a summer class by English professor James Ayers on the premise that the best way to explore Shakespeare’s plays is to perform them, the program has grown into a year-round effort that reaches students from elementary school through college. Most performances still take place in a now iconic nineteenth-century barn at the Winedale Historical Complex east of Austin, in the tiny town of Round Top. Though it’s an unlikely setting, both students and audiences alike swelter through the Texas summer heat to immerse themselves in Shakespeare’s works.

The Bard, though, has long been a welcome figure on the Forty Acres. Leslie Waggener (photo at left), one of the University’s original eight professors and a longtime Chair of the Faculty, inspired students in his English classes to organize a Shakespearean Club in 1885, during UT’s third academic year. When time allowed, he often presented lectures about Shakespeare to appreciative audiences across the state. “People who went to the opera house last night were entertained far beyond their most sanguine hopes,” gushed the Fort Worth Gazette about a talk Waggener delivered in 1887.

The Bard, though, has long been a welcome figure on the Forty Acres. Leslie Waggener (photo at left), one of the University’s original eight professors and a longtime Chair of the Faculty, inspired students in his English classes to organize a Shakespearean Club in 1885, during UT’s third academic year. When time allowed, he often presented lectures about Shakespeare to appreciative audiences across the state. “People who went to the opera house last night were entertained far beyond their most sanguine hopes,” gushed the Fort Worth Gazette about a talk Waggener delivered in 1887.  Internationally known Shakespeare scholar Mark Liddell taught at UT in the late 1890s and mesmerized students with his occasional in-class performances. Liddell published an essay titled “Botching Shakespeare” in the October, 1898 Atlantic Monthly that’s still referenced in the current debate over whether to translate Shakespeare’s plays into modern English. In 1905, the Ashbel Literary Society, a ladies-only student organization, surprised everyone with a performance of A

Internationally known Shakespeare scholar Mark Liddell taught at UT in the late 1890s and mesmerized students with his occasional in-class performances. Liddell published an essay titled “Botching Shakespeare” in the October, 1898 Atlantic Monthly that’s still referenced in the current debate over whether to translate Shakespeare’s plays into modern English. In 1905, the Ashbel Literary Society, a ladies-only student organization, surprised everyone with a performance of A  Mid-Summer Night’s Dream that featured an all-female cast, a reversal from Shakespeare’s time when women were prevented from appearing on stage and all of the roles were played by men. The show was such a hit, the Ashbel staged As You Like It the following year. In 1909, the Curtain Club was founded as the University’s first formal dramatic association. It was named for the Curtain Theater, one of several commercial stages – along with the Globe – that were operating in London during Shakespeare’s career.

Mid-Summer Night’s Dream that featured an all-female cast, a reversal from Shakespeare’s time when women were prevented from appearing on stage and all of the roles were played by men. The show was such a hit, the Ashbel staged As You Like It the following year. In 1909, the Curtain Club was founded as the University’s first formal dramatic association. It was named for the Curtain Theater, one of several commercial stages – along with the Globe – that were operating in London during Shakespeare’s career.

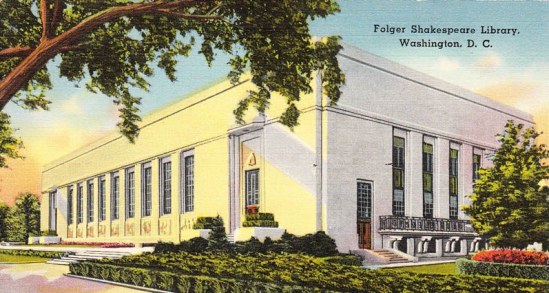

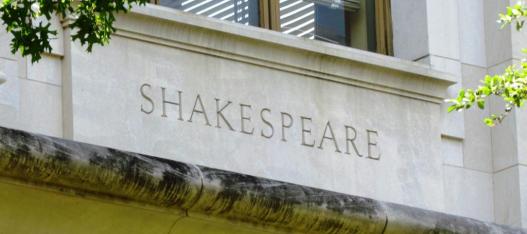

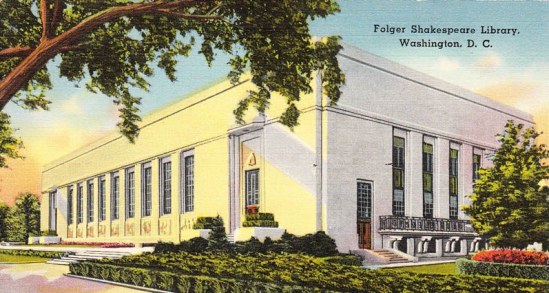

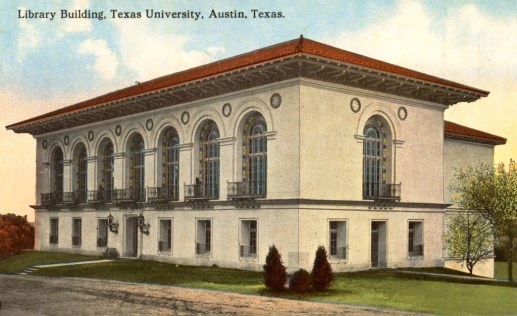

Today, “Shakespeare” adorns the University’s Main Building. Constructed in the 1930s to serve as the central library, the names of fourteen literary giants – Aristotle, Homer, Cervantes, Moliere, and Mark Twain, among them – were symbolically engraved in limestone along the east and west walls. Shakespeare was placed in the northeast corner. And, just in case more UT-Shakespeare connections were needed, Paul Cret, the architect of the Main Building and Tower, was also the designer of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. Cret was finishing his plans for the Shakespeare Library just as the University hired him to be its consulting architect.

Above and left: Two buildings which share the same architect. In 1928, oil magnate Henry Folger hired Paul Cret, then head of the architecture school at the University of Pennsylvania, to design a library and theater in Washington, D.C. to make Folger’s extensive collection of rare Shakespeareana available to the public. Two years later, as Cret was finishing the project and construction was about to begin, the University of Texas appointed him as its consulting architect. Cret completed his campus master plan for UT – which included the Main Building and Tower – in 1933, the same year the Folger Shakespeare Library opened. Click on an image for a larger view.

Above and left: Two buildings which share the same architect. In 1928, oil magnate Henry Folger hired Paul Cret, then head of the architecture school at the University of Pennsylvania, to design a library and theater in Washington, D.C. to make Folger’s extensive collection of rare Shakespeareana available to the public. Two years later, as Cret was finishing the project and construction was about to begin, the University of Texas appointed him as its consulting architect. Cret completed his campus master plan for UT – which included the Main Building and Tower – in 1933, the same year the Folger Shakespeare Library opened. Click on an image for a larger view.

~~~~~~~~~~

In 1914, at its annual conference in Chicago, the Drama League of America discussed the upcoming 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 1916 and voted to bring about “a great national Shakespeare Tercentenary Celebration.” The group didn’t have the resources to coordinate a single, coast-to-coast effort. Instead, it encouraged local events organized by communities, schools, and colleges. It held press conferences, contacted civic organizations, and published pamphlets filled with ideas for parades, day-long Shakespeare festivals, music and steps to old English dances, and ideas for easily-made Elizabethan costumes (image at right).

In 1914, at its annual conference in Chicago, the Drama League of America discussed the upcoming 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 1916 and voted to bring about “a great national Shakespeare Tercentenary Celebration.” The group didn’t have the resources to coordinate a single, coast-to-coast effort. Instead, it encouraged local events organized by communities, schools, and colleges. It held press conferences, contacted civic organizations, and published pamphlets filled with ideas for parades, day-long Shakespeare festivals, music and steps to old English dances, and ideas for easily-made Elizabethan costumes (image at right).

The Drama League’s efforts were incredibly successful. Despite the anxiety of an economic recession and a heated debate over whether the United Sates should enter the war in Europe, much of 1916 was given over to a national veneration of Shakespeare. The New York Times sponsored a weekly supplement devoted to the Bard, the city of Saint Louis  boasted five performances of As You Like It with a cast of 1,000 persons, the University of Iowa organized a well-attended outdoor festival (photo at left). Commemorative parks were dedicated, schoolchildren learned Morris dances, and Shakespeare parties were a national fad.

boasted five performances of As You Like It with a cast of 1,000 persons, the University of Iowa organized a well-attended outdoor festival (photo at left). Commemorative parks were dedicated, schoolchildren learned Morris dances, and Shakespeare parties were a national fad.

Most organizers took their cues from the Drama League and sponsored one or two of the published suggestions: a parade and performance of a play, for example, or an academic lecture as part of a library exhibit. But Shakespeare was especially welcome in Austin. The University of Texas did them all, and more.

~~~~~~~~~

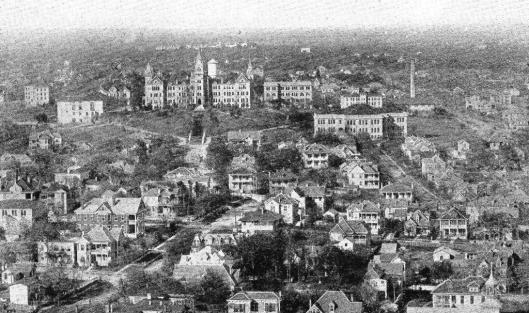

Above: The University campus in 1916. “Old Main” in the center has been replaced by the current Main Building and Tower.

For UT, Shakespeare fever arrived in 1915 at a spring meeting of the faculty, when English professor Reginald Griffith proposed a campus-wide celebration. A PhD graduate of the University of Chicago, Griffith came to Austin in 1902 for what would be a fifty-year career. Passionate about rich libraries and rare books, he initiated with UT president Robert Vinson – and enabled by a generous $225,000 gift from George Littlefield – the 1917 purchase of the John Wrenn Library in Chicago, the first step in creating a world class literary research center at the University. Just before his retirement, Griffith spearheaded the effort to found the University of Texas Press in 1950.

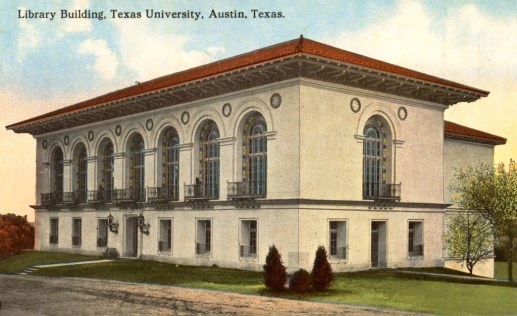

The faculty approved the idea unanimously. An organizing committee of five, with Griffith as chair, was appointed, including Latin professor Ed Fay, history professor Eugene Barker, Aute Richards from zoology, and faculty secretary (and noted cowboy song collector) John Lomax. By mid-July, the initial plans were announced in the Austin Daily Statesman, but were decidedly tame and traditional. There would be an exhibit in the University Library, distinguished scholars would be invited for guest lectures, and a professional troupe would be hired to present several Shakespeare plays “for the delight and instruction of the students and faculty.”

The faculty approved the idea unanimously. An organizing committee of five, with Griffith as chair, was appointed, including Latin professor Ed Fay, history professor Eugene Barker, Aute Richards from zoology, and faculty secretary (and noted cowboy song collector) John Lomax. By mid-July, the initial plans were announced in the Austin Daily Statesman, but were decidedly tame and traditional. There would be an exhibit in the University Library, distinguished scholars would be invited for guest lectures, and a professional troupe would be hired to present several Shakespeare plays “for the delight and instruction of the students and faculty.”

Griffith, though, wasn’t satisfied. Just as the future Shakespeare at Winedale program was built upon the tenet of understanding Shakespeare through performance, Griffith sought to involve as much of the University community as possible, and not as mere spectators. He prodded the committee for more ideas and sought advice from friends and colleagues. By the end of the 1915 fall term, plans for a far more ambitious Shakespeare Tercentenary had emerged.

~~~~~~~~~~

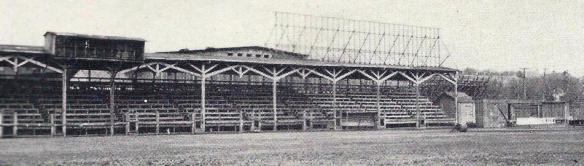

For several years, Eunice Aden, as Director of Physical Training for Women (photo at right), had organized an annual spring exhibition of games, exercises, and dances by hundreds of participating co-eds. Held at the University’s athletic field (old Clark Field, about where the O’Donnell Building and the Gates-Dell Computer Science complex are today), it was meant, in part, to promote the still not-completely-accepted idea of women in sports. Griffith approached Aden about substituting a nighttime Shakespeare commemoration for her usual program, making it instead an evening of old English folk dances, along with an original artistic tribute to the Bard. Aden, who as a UT student had starred as Orlando in the 1906 Ashbel Society production of As You Like It, readily agreed. A dozen sections of the men’s gym classes were recruited to be partners with the girls.

For several years, Eunice Aden, as Director of Physical Training for Women (photo at right), had organized an annual spring exhibition of games, exercises, and dances by hundreds of participating co-eds. Held at the University’s athletic field (old Clark Field, about where the O’Donnell Building and the Gates-Dell Computer Science complex are today), it was meant, in part, to promote the still not-completely-accepted idea of women in sports. Griffith approached Aden about substituting a nighttime Shakespeare commemoration for her usual program, making it instead an evening of old English folk dances, along with an original artistic tribute to the Bard. Aden, who as a UT student had starred as Orlando in the 1906 Ashbel Society production of As You Like It, readily agreed. A dozen sections of the men’s gym classes were recruited to be partners with the girls.

A performance of sixteenth century English dances, though, needed a proper setting. Phi Alpha Tau, a professional fraternity whose membership then drew from the campus literary, debate, and dramatic clubs, volunteered to design and build a replica of an English village that would stretch across the far side of the football field as a backdrop. The idea quickly expanded into a full Bartholomew Fair, what amounted to the first Renaissance Fair in Texas. Spectators would watch the dance performance seated in the stands, and then be invited on to the field to join in the fair afterward.

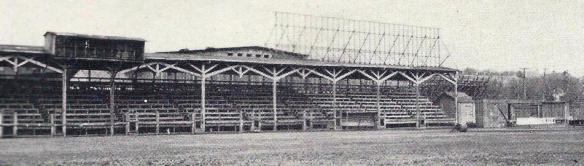

Above: Clark Field, looking toward the covered west stands. A Bartholomew Fair was constructed along the east half of the field.

As Clark Field wasn’t lighted, physics professor LeRoy Brown offered to supervise a group of science and engineering students that would install spotlights as temporary illumination, along with special lighting effects for the fair. Music professor Frank Reed took on the responsibility for the live music needs for the evening, found the scores to English folk dances and other appropriate tunes, and recruited the University band and singing groups.

~~~~~~~~~~

Thus far, more than a thousand of the University’s 2,600 enrolled students were involved. What about the rest? Inspiration came from the home front, as Griffith’s wife, Alice, had been researching previous Shakespeare celebrations, particularly the first Shakespeare Jubilee that took place in Stratford in 1769. Among the many scheduled events was a pageant, a parade of costumed characters from Shakespeare’s plays. Though rainy weather had cancelled the 1769 pageant, it was included in future Shakespeare celebrations and had long been popular. Why not stage a pageant on the campus?

Before long, a pageant committee had organized, chaired by home economics professor Mary Gearing and composed of faculty, wives of professors, and friends of the University. The committee created a dozen parade units, depicting either scenes from plays or snapshots of Shakespeare’s life, and assigned each to an academic department or student organization. To visually distinguish each group, the committee went so far as to select “color schemes” for the costumes.

~~~~~~~~~~

With the inclusion of a procession, plans for the University’s Shakespeare Tercentenary were at last complete. A five-day celebration, from April 22 – 26, would include a library exhibit, lectures by visiting academics, performances of Shakespeare plays by a professional troupe from New York City, an Elizabethan Revel with folk dances, a Bartholomew Fair, and, to start off the festivities, a great Shakespeare Pageant. For UT, it was the most ambitious project yet attempted.

Funding all of this, of course, quickly became an issue. The University could afford to bring visiting scholars and hire a professional troupe, but had limited resources to provide the lumber, nails, and paint for the Bartholomew Fair, or the materials and labor needed to create thousands of Elizabethan costumes. Concessions were to be sold at the pageant and the fair, and a planned twenty-five cent admission to Clark Field would all help cover the costs, but the money was needed beforehand. To the rescue again came Dr. Griffith, who fronted the needed funds, a sizeable risk for an associate professor earning a $2,200 salary. So that Griffith could concentrate on the tercentenary program, UT athletic director Theo Bellmont (image, above right) volunteered for business manager duties.

Funding all of this, of course, quickly became an issue. The University could afford to bring visiting scholars and hire a professional troupe, but had limited resources to provide the lumber, nails, and paint for the Bartholomew Fair, or the materials and labor needed to create thousands of Elizabethan costumes. Concessions were to be sold at the pageant and the fair, and a planned twenty-five cent admission to Clark Field would all help cover the costs, but the money was needed beforehand. To the rescue again came Dr. Griffith, who fronted the needed funds, a sizeable risk for an associate professor earning a $2,200 salary. So that Griffith could concentrate on the tercentenary program, UT athletic director Theo Bellmont (image, above right) volunteered for business manager duties.

~~~~~~~~~~

Above: The University of Texas Library, currently the Architecture and Planning Library in Battle Hall, site of the 1916 Shakespeare exhibit.

By February 1916, much of the campus community was actively preparing for the tercentenary. Massive rehearsals for folk dances took place in the women’s gym, then housed in a temporary wooden structure about where the Texas Union stands today. University Librarian John Goodwin assembled an exhibit in a room on the first floor of the library (Battle Hall), with books, maps, photographs, and other materials about Shakespeare and Elizabethan England.

The exhibit, though, quickly became a critical resource, heavily consulted by the members and friends of Phi Alpha Tau as they designed and built their English hamlet for the Bartholomew Fair. Home economics students, under the advice of Professor Mary Gearing, used the exhibit to study Elizabethan textiles and fashion, and sketched dozens of historically accurate costumes that were posted on bulletin boards all over campus.

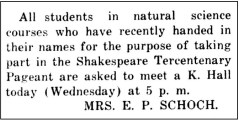

Left: Throughout the spring, notices about meetings and rehearsals for the Shakespeare Tercentenary regularly appeared in The Daily Texan student newspaper.

The costumes were, by far, the most time consuming. Thousands were needed. Materials for hats and suits were purchased at wholesale prices. Along with student volunteers, every tailor and dressmaker in Austin was employed. Even the sinks in the chemistry lab building were commandeered to dye endless pairs of stockings just the right shade.

In the meantime, the University advertised the upcoming celebration in newspapers throughout the state. Many of the hotels in Austin were filled.

~~~~~~~~~~

Above: Pat Holmes (in the wheelbarrow) stars as Falstaff as fellow social science students recreate a scene from The Merry Wives of Windsor in the Shakespeare pageant.

At precisely 6 p.m. on Saturday, April 22nd, a trumpet fanfare, played in front of the Victorian-Gothic old Main Building, heralded the start of the Shakespeare Pageant. The mile-long parade route started on the east side and moved counter-clockwise along the walkway that enclosed the square, forty acre campus. Twelve flags were spaced evenly on the course to mark the stops where the pageant groups would perform.

According to the Austin American, “The last rays of a brilliant sunset, reluctant to retire beyond vision of such a resplendent scene, shed multi-colored rays over the rollicking actors in the pageant. On every hand minstrels darted, jesters chided and bantered, and apple-sellers and sandwich peddlers adjured the crowd to purchase their wares. Twelve groups of players composed the main body of the pageant, portraying some dramatic moment of one of Shakespeare’s plays. Minstrels preceded each group, joyously rendering ballads and accompanying themselves with mandolins and guitars.”

Above: With Grace Denny as Rosalind (far left), natural sciences students portray As You Like It. All are holding young corn stalks, meant to depict the trees in the forest of Arden.

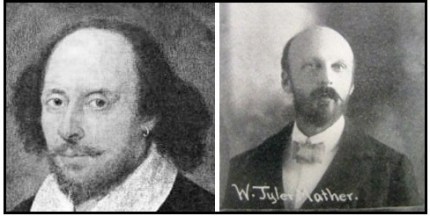

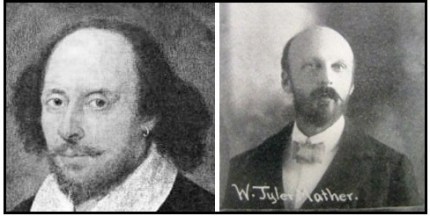

The Department of Social Sciences took on The Merry Wives of Windsor, decked out in “biscuit colored outfits in red trim,” while natural science students chose As You Like It in costumes of “forest green and brown.” Appropriately, the law department reenacted the trial scene from The Merchant of Venice. Ancient languages claimed Julius Caesar. Modern languages went with Taming of the Shrew, education students opted for King Richard III, home economics selected The Winter’s Tale, and the engineers boldly chose Hamlet. The remaining groups depicted scenes from Shakespeare’s life. At the end of the procession was the Bard himself, played by Dr. Tyler Mather, chair of the physics department.

Above: Good casting? Dr. Tyler Mather (right), chair of the physics department, played Shakespeare in the tercentenary pageant.

An estimated 10,000 spectators gathered to see the parade, more than half of them sporting their own, homemade Elizabethan costumes. They stayed well after sunset and watched the parade by the light of electric lamps only recently installed along the walk.

The pageant concluded, the crowd hurried to fill the west stands of Clark Field for the 8 p.m. Elizabethan Revel. Under the gaze of special lighting and accompanied by the twenty-piece University band, hundreds of UT students performed a series of English folk dances: Morris dances, the Sailor’s Hornpipe, and others. Next, the all-girl advanced modern dance class presented an interpretive, original piece which depicted an aging Shakespeare, retired from the stage, returning his literary gifts to each of the Nine Muses. “The various young ladies and their attendants captivated the audience by the gracefulness and beauty with which they danced their respective parts,” reported the Cactus yearbook.

The pageant concluded, the crowd hurried to fill the west stands of Clark Field for the 8 p.m. Elizabethan Revel. Under the gaze of special lighting and accompanied by the twenty-piece University band, hundreds of UT students performed a series of English folk dances: Morris dances, the Sailor’s Hornpipe, and others. Next, the all-girl advanced modern dance class presented an interpretive, original piece which depicted an aging Shakespeare, retired from the stage, returning his literary gifts to each of the Nine Muses. “The various young ladies and their attendants captivated the audience by the gracefulness and beauty with which they danced their respective parts,” reported the Cactus yearbook.

After the dance program, the audience was invited on to the field for the Bartholomew Fair. The Boar’s Head “Tavern” served shepherd’s pie and family-friendly libations. Puppet shows, mock sword fights, wrestling matches, and fortune telling provided entertainment, and fairgoers could try their own hand at archery, lawn bowling, and folk dancing. The Austin Daily Statesman called it a “gorgeous jollification,” and the party continued well into the night.

Sunday, April 23rd, was the anniversary date of Shakespeare’s passing, but also turned out to be Easter Sunday. The University, along with most of Austin, was closed for the day. No matter. Caught up in the spirit of the weekend, most of the city’s clergy found a way to weave Shakespeare into their Easter sermons.

The tercentenary continued through the following Wednesday, as UT president William Battle suspended classes each day at noon so as many students as possible could attend lectures by visiting scholars in the Old Main auditorium. Addresses were delivered by John Manly of the University of Chicago, Barrett Wendell of Harvard, and former UT law professor and regent Robert Batts. In the evenings, the Cliff Deveraux troupe from New York performed Shakespeare plays outdoors in the southeastern corner of the campus, the audience sitting on the hillside where the Graduate School of Business building now stands. Wednesday afternoon, the campus was given over to the children of the Baker, Winn, and Wooldridge elementary schools who held their own Shakespeare pageant and a Maypole dance.

The tercentenary continued through the following Wednesday, as UT president William Battle suspended classes each day at noon so as many students as possible could attend lectures by visiting scholars in the Old Main auditorium. Addresses were delivered by John Manly of the University of Chicago, Barrett Wendell of Harvard, and former UT law professor and regent Robert Batts. In the evenings, the Cliff Deveraux troupe from New York performed Shakespeare plays outdoors in the southeastern corner of the campus, the audience sitting on the hillside where the Graduate School of Business building now stands. Wednesday afternoon, the campus was given over to the children of the Baker, Winn, and Wooldridge elementary schools who held their own Shakespeare pageant and a Maypole dance.

One last fling was held Thursday evening. An all-University dance in the women’s gym provided an excuse to don those Elizabethan costumes a final time. Class attendance Friday morning was reportedly a bit sparse.

One last fling was held Thursday evening. An all-University dance in the women’s gym provided an excuse to don those Elizabethan costumes a final time. Class attendance Friday morning was reportedly a bit sparse.

“Never before has a single activity been more enthusiastically participated in by a larger number of our student body than the Shakespeare Tercentenary,” reported The Daily Texan student newspaper. “Its influence educationally was great. The institution was imbued with a new sense of the artistic and cultural. It has done a lasting good.” Professor Griffith, who was fully reimbursed from the earnings of the Bartholomew Fair, was praised from all corners of the campus. “He shouldered the whole responsibility, financial and otherwise,” lauded the Texan. “Such loyal public service cannot be commended too highly.”