And the near demise of Texas A&M

The University of Texas alumni magazine Alcalde arrived only after a Herculean overhaul of the Alumni Association, an unprecedented public relations campaign to promote higher education, a sumptuous turkey dinner, a near-fatal bout of appendicitis, and a legislative debate over merging Texas A&M with the University in Austin.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

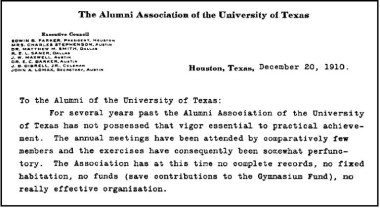

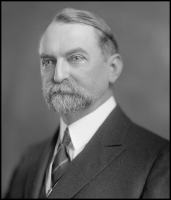

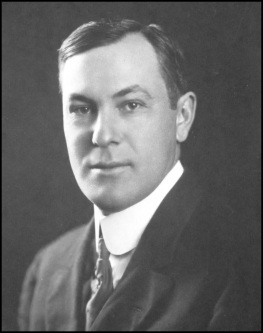

It wasn’t the usual holiday greeting. Less than a week before Christmas, on December 20, 1910, University of Texas Alumni Association President Ed Parker (right) wrote a bluntly candid letter to his fellow graduates. “The Association has at this time,” he explained, “no complete records, no fixed habitation, no funds, no really effective organization.” Alumni dues were a dollar a year, but no one bothered to pay them. The treasury had been empty since 1905 and the office of treasurer left vacant. “That such a condition should not be permitted to continue does not admit of argument.”

It wasn’t the usual holiday greeting. Less than a week before Christmas, on December 20, 1910, University of Texas Alumni Association President Ed Parker (right) wrote a bluntly candid letter to his fellow graduates. “The Association has at this time,” he explained, “no complete records, no fixed habitation, no funds, no really effective organization.” Alumni dues were a dollar a year, but no one bothered to pay them. The treasury had been empty since 1905 and the office of treasurer left vacant. “That such a condition should not be permitted to continue does not admit of argument.”

Founded on Wednesday, June 17, 1885 by the 34 members of UT’s first two graduating classes – 1884 and 1885 – the University’s alumni group was full of potential. In its first years it provided several gifts and scholarships, and the group raised $1,000 as one-third of the cost of UT’s first athletic field. By 1910, though, the 25-year old Association had languished.

What activity remained was centered on a sparsely-attended “Alumni Day,” an annual meeting in June held in conjunction with the University’s Commencement Week. The meeting highpoints included a formal “alumni address” speech, a debate and selection of next year’s speaker, and then officer elections before the group adjourned to a barbecue lunch.

Parker, an 1889 graduate and Houston lawyer, was elected president at the June 1910 meeting, but didn’t fully realize the somber state of alumni affairs until his predecessor, Will Crawford, cordially stopped by Parker’s office months later. The two had a lengthy conversation and Parker resolved to place the Association on a more prosperous course.

After further discussions and a meeting with his fellow officers in the Executive Council, Parker crafted five ambitious goals intended to resuscitate the Alumni Association:

- Acquire a permanent alumni secretary “charged with the execution of such plans as the association may adopt.”

- “Furnish and equip” a room on campus as an alumni headquarters.

- Add class reunions to the annual June meeting to increase interest and attendance.

- Enforce the rule requiring $1 annual dues. With approval of the Executive Council, a $50 life membership was created, payable all at once or in $10 installments over five years.

- Establish an alumni magazine.

University President Sidney Mezes was quick to support Parker’s objectives, and offered to fulfill two items on the list:

- First, Mezes found an alumni secretary. John Avery Lomax earned his Bachelor of Arts degree at UT in 1897, and then spent six years as the University’s registrar before he was hired as an English instructor at the A&M College of Texas (now Texas A&M University). In 1906, Lomax took a sabbatical, went to Harvard on a scholarship, earned his master’s degree, and fulfilled a childhood ambition to collect and preserve western cowboy and folk songs. Encouraged by his Harvard professors, Lomax solicited songs through newspapers and journeyed throughout the west whenever time and funds permitted. In Fort Worth, he met cowhands who knew the words to “The Old Chisolm Trail” and discovered a gypsy woman who sang, “Git Along Little Doggies.” In San Antonio, an African American former trail cook who was then managing a saloon performed “Home on the Range.” Back in College Station, Lomax compiled the music into a book titled Cowboy Songs and other Frontier Ballads. It was to appear in November 1910 and would eventually make Lomax internationally famous.

Around the same time, Mezes recruited Lomax back to Austin to serve as Secretary of the University and Assistant Director of the Extension Department, and he was to start with the fall 1910 term. As an opportune coincidence, Lomax had also been elected secretary of the Alumni Association at the same meeting Parker was made president. Normally, the secretary – as with the other officers – served in a volunteer capacity, but Mezes made it a professional one. He added “Alumni Secretary” to Lomax’s job description, which provided the first paid staff position for the Association and tied the group more closely to the University. Lomax earned a $2,200 salary, though it would be raised to $2,700 within two years.

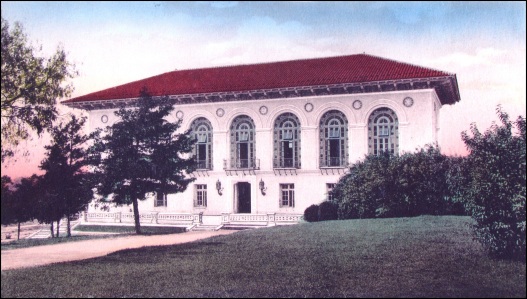

Above: The University Library – today’s Battle Hall – under construction in 1910 .(from UT’s Alexander Architectural Archives)

- Mezes also offered the Association a home. In 1910, the University’s new Library (today’s Battle Hall) was well under construction. When finished the following year, it was expected to have enough extra room that UT’s administrative offices, including the president’s office, would be moved to the first floor. Mezes was confident that once he relocated to the new building, the Board of Regents would approve the use of his current office, room 119 in Old Main, as the Alumni Room, a new campus headquarters for the Association.

Having already attained two of his goals, Parker’s December letter was mailed to about 2,800 alumni, which laid out the troubling state of the Association and outlined the five objectives. “There can be no question,” Parker wrote, “but that a state university . . . has need for an active, vigilant, and loyal working body of alumni to look out for its interests.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Through the spring of 1911, Parker and the Executive Council diligently pursued the final three objectives. The June meeting and class reunions for UT’s first 10 graduating classes (1884 to 1893) were advertised in newspapers statewide. Parker sent personal letters to each member of the reunion classes and President Mezes did the same a few weeks later. “In case it is possible for you to attend,” wrote Mezes, “kindly notify me by wire, so that proper provision can be made for your reception and entertainment.”

Above: The Engineering Building, now the Gebauer Building. Opened in 1904, it’s the oldest surviving building on the Forty Acres. Above the ground floor labs and first floor offices, the alumni met in the second floor lecture hall, on the right side with the arched windows.

At 9:30 a.m. on the sunny and warm Monday morning of June 12, 1911, nearly 250 graduates gathered for the annual meeting, held in the second floor lecture hall of the Engineering Building (today’s Gebauer Building). With the entire nation experiencing an early summer heat wave, the windows were opened to catch any southeastern breezes that ventured up from the Gulf of Mexico.

The news was encouraging. Just over 600 alumni had paid their $1 dues and pledged to continue their payments in the future. Three alumni were $50 life members, and 36 more were on the installment plan. John Lomax was formally introduced as the group’s Alumni Secretary, and the Board of Regents had officially approved repurposing room 119 in Old Main as the new Alumni Room. The Association’s first class reunions were to be held later that evening at the Austin Country Club.

In the course of the meeting, the group approved the creation of 31 volunteer “district secretaries,” one in each state senatorial district, to organize social gatherings on March 2, Texas Independence Day. Meant to celebrate both the state and the University, the annual event quickly became a catalyst for the creation of local alumni chapters. (See Why Texas Exes Celebrate March 2nd).

In the course of the meeting, the group approved the creation of 31 volunteer “district secretaries,” one in each state senatorial district, to organize social gatherings on March 2, Texas Independence Day. Meant to celebrate both the state and the University, the annual event quickly became a catalyst for the creation of local alumni chapters. (See Why Texas Exes Celebrate March 2nd).

Above right: The Austin chapter of the Alumni Association organized in 1913 with a luncheon at the Driskill Hotel.

Also approved was a resolution to give the Executive Council authority “to establish and provide for a University of Texas periodical,” though it was felt that a magazine should be put on hold for a year. Instead, Lomax was to complete an updated alumni directory.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: The University’s Old Main, with the newly opened Library on the left.

The surprise of the day came from Will Hogg, namesake for the W. C. Hogg Building on campus. The son of former Governor James Stephen Hogg, an 1897 law school graduate, and, like Parker, a Houston lawyer, Will Hogg fully supported Parker’s efforts to transform the alumni group “from a wishing organization to a working organization.”

At a time when a majority of the U.S. population remained unconvinced about the value of a college education, the 36-year old Hogg was believed that the only way for state-funded colleges and universities in Texas to be adequately financed and supported was for more Texans to truly understand what was happening on campus. While he had mulled over the idea for years, the momentum Parker was building with the alumni presented a ripe opportunity to put thoughts into action. Hogg proposed an ambitious and unprecedented five-year program to promote higher education to the people of Texas.

He originally called it “The Organization for the Enlargement and Extension by the State of the University Plan of Higher Education in Texas.” What a mouthful. It was quickly shortened to “The Hogg Organization.”

According to its proposed by-laws, the Hogg Organization was to be overseen by the President of the Ex-Students’ Association, President of the University, and Chair of the Board of Regents. Committees of volunteers would be organized to handle specific tasks, and Hogg explained that Arthur Lefevre, an 1895 UT civil engineering graduate, was to be hired as secretary.

While it would rest under the umbrella of the Alumni Association, Hogg planned to take on the funding himself and promised to find enough contributors to be able to spend $30,000 for five years, or $150,000 total, equivalent to more than $4.5 million today. The alumni enthusiastically supported the idea, many became contributors, and Hogg was as good as his word. In four months, he obtained enough pledges to finance the entire project. (No subscription larger than $250 per year was accepted.)

Over the next five years, the Hogg Organization made an enormous impact on the state promoting a single idea: that higher education was vital to the future prosperity of Texas. Articles regularly appeared in newspapers statewide, and it received coverage from as far away as Boston. Informational posters and charts espousing the benefits of a university education were placed in courthouses, libraries, and chambers of commerce. “Higher Education Day” programs were held in thousands of Texas public schools – most of them one-teacher schoolhouses in rural communities – to inform and encourage students to consider going on to college. (At the time, in-state tuition to UT and other state-supported colleges was free, paid through a legislative appropriation.) A series of pamphlets, published by the Hogg Organization and mailed to thousands across Texas, promoted the “cultural value” of education and detailed the economic impact of higher education on the state. Elaborate exhibits were placed at county fairs, where University alumni volunteers were there to explain and answer questions.

Perhaps its best publicity effort was in hiring about 30 recent graduates who represented every college and university in Texas, both publicly and privately funded. As something akin to higher education missionaries, they canvased the state, especially small towns, where they spoke about their own collegiate experiences. As John Lomax later remarked, “These men were carefully selected, and the hope of what they could accomplish lay in the fact that they themselves were Texas people who could talk pretty well and could show the people of the state what a college education had done for them. A great deal of good was done by these men.”

Of course, as the Hogg Organization was considered a project of the Alumni Association, the public profile of the latter was raised considerably.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

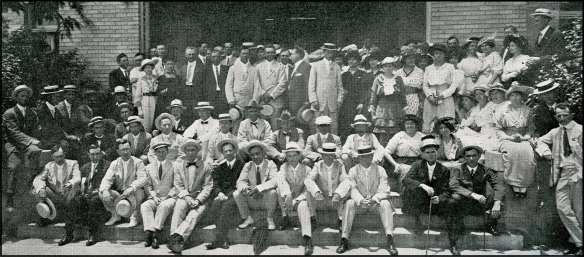

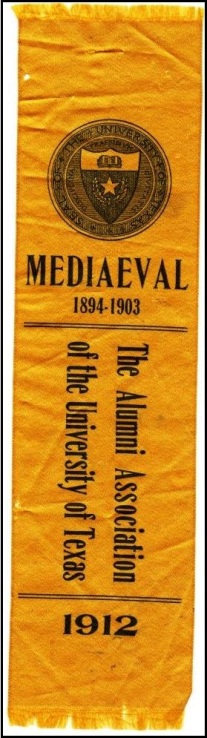

By June 1912, a year-and-a-half after Parker’s dire letter, the transformation of the Alumni Association was nothing short of remarkable. Attendance for the June 10 annual meeting had doubled to 500 and was moved to the newly-opened YMCA Building at the corner of 22nd and Guadalupe Streets. Dues-paid memberships had topped 1,000 persons. Reunions were organized for the second ten graduating classes (1894 to 1903), and the first ever Alumni vs. ‘Varsity Baseball Game was held, pitting former UT baseball stars against Coach Billy Disch and his current team.

The signature event of the evening was a torchlight and colored lantern procession. Alumni assembled on the West Walk (the future West Mall) and with the University Band leading the way, paraded on the streets around the perimeter of the Forty Acres. Colorful floats built by academic departments and student organizations joined the “devoted foot-cavalry,” as Lomax described it, “plugging along amid dust and hilarity.” Student and Austin spectators crowded the route.

The signature event of the evening was a torchlight and colored lantern procession. Alumni assembled on the West Walk (the future West Mall) and with the University Band leading the way, paraded on the streets around the perimeter of the Forty Acres. Colorful floats built by academic departments and student organizations joined the “devoted foot-cavalry,” as Lomax described it, “plugging along amid dust and hilarity.” Student and Austin spectators crowded the route.

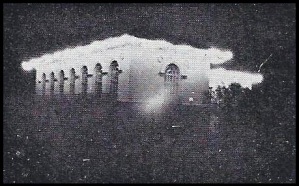

To prepare the campus, “the Senior Engineers have strung thousands of electric globes along the main walks,” reported the Austin Statesman. Additional strings of alternating orange and white lights were hung under the eaves of the new Library (above right) and the front of the old Main Building was brightly floodlit. The parade wound up at a wooden stage just west of Old Main, where the participants were entertained by skits and songs performed by UT students.

“Everybody was tired, but everybody was happy,” reported Lomax. “Alumni Day, 1912, was at an end – a day filled with much pleasure for many people, and a day marking probably the largest and most successful home-coming of old students the University has ever known.”

“Everybody was tired, but everybody was happy,” reported Lomax. “Alumni Day, 1912, was at an end – a day filled with much pleasure for many people, and a day marking probably the largest and most successful home-coming of old students the University has ever known.”

The most important and far-reaching events, though, were during the morning business meeting. In an effort to recruit still more participation (and, it was argued, missing friends who hadn’t completed their degrees), the alumni approved a constitutional amendment to expand membership from graduates-only to anyone who had attended the University. Hereafter, the UT Alumni Association was renamed the Ex-Students’ Association of the University of Texas.

The group also gave the go-ahead for an alumni magazine and set a target date of January 1, 1913 for the first issue. A committee was appointed to get the ball rolling and meet with President Mezes about potential financial assistance.

Left: Ribbon from the 1912 alumni meeting. In lighthearted fashion, the alumni were divided into three 10-year sets and given special designations. The oldest group was dubbed the “Ancients,” the middle group called the “Medievals,” and the most recent graduates were the “Old Timers.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Of course, deciding to launch a periodical wasn’t the same as putting all of the pieces together. The magazine needed a name. There wasn’t yet an editor, editorial board, final decisions about content, completed articles, photos and illustrations, a cover design, advertisements to help defray printing costs, and a host of other details. Given all of the work that needed to be done, the New Year’s publication date wasn’t all that distant.

Lomax didn’t waste any time, and used the summer to solicit possible article contributors for the first issue. “The Alumni Association of the University of Texas has voted to begin an Alumni Magazine,” Lomax wrote to Alexander Macfarlane, who led the physics department from 1885 to 1894 and had since retired to Canada. “One purpose of the publication is to obtain a record of the early days of the institution from the men who were the chief actors in making this history.” McFarlane declined, but Lomax had better luck with John Mallet. A longtime chemistry professor at the University of Virginia, Mallet was among the eight-member inaugural UT faculty in 1883 and served as the faculty chair. He obliged with a three-page “Recollections of the First Year.” Lomax’s request was a timely one, as Mallet passed away only a few months later, in November.

In the meantime, an alumni committee approached President Mezes about financial support. Mezes offered to help, but wanted the alumni publication to replace The University of Texas Record. A UT-sponsored journal first published in 1899, it provided a wealth of information about academics and student life on the Forty Acres, but as many of the topics would overlap with an alumni magazine, it didn’t make sense to fund both. About 5,000 copies were printed for each issue of the Record, and Mezes hoped the new magazine would have the same circulation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

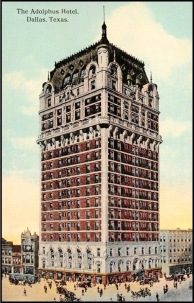

Progress on the magazine continued through autumn. On Friday morning, October 18, 1912, the Ex-Students’ Association Executive Council assembled in the brand-new and majestic Adolphus Hotel (left), opened less than two weeks beforehand in downtown Dallas. President Mezes attended as well. The group officially endorsed the alumni magazine and appointed an eight-person editorial board, which included Lomax. Among its members: Dr. Harry Benedict, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Eugene Barker, chair of the UT history department, and Fritz Lanham, a 1900 graduate who had served as the first editor-in-chief of The Texan student newspaper. In addition to the board, an ad hoc committee of Association Vice President John Philip, Will Hogg, and John Lomax was organized to look after the business affairs for the first issue.

Progress on the magazine continued through autumn. On Friday morning, October 18, 1912, the Ex-Students’ Association Executive Council assembled in the brand-new and majestic Adolphus Hotel (left), opened less than two weeks beforehand in downtown Dallas. President Mezes attended as well. The group officially endorsed the alumni magazine and appointed an eight-person editorial board, which included Lomax. Among its members: Dr. Harry Benedict, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Eugene Barker, chair of the UT history department, and Fritz Lanham, a 1900 graduate who had served as the first editor-in-chief of The Texan student newspaper. In addition to the board, an ad hoc committee of Association Vice President John Philip, Will Hogg, and John Lomax was organized to look after the business affairs for the first issue.

Just over a month later, on Wednesday, November 27 (Thanksgiving Eve) the editorial board gathered in Austin for its organizational meeting. Five additional members had been selected, including Richard Fleming and Mary Batts as student editors, who would contribute news about campus life and Longhorn sports.

The group met at the Lomax family home in west campus at 910 West 26th Street, a one-year old, two-story, yellow-brick bungalow with a hillside view of what today is North Lamar Boulevard and Shoal Creek, and where a pre-Thanksgiving turkey feast awaited everyone. “Carefully cooked by Mrs. Lomax,” Harry Benedict recounted years later, “in strict accord with all the finer principles of gastronomy, it was set, not before a king, but before certain unroyal personages who were met to destroy the turkey and to found a Texas alumni magazine.”

After dinner, the first order of business was to select an editor-in-chief, at the time an entirely volunteer position. Fritz Lanham (at right) received the nod. A lawyer from Weatherford (just west of Fort Worth), he was best-known on the Forty Acres as the founder and first editor of the Texan newspaper. The group hoped Lanham would bring that experience to the new alumni magazine.

After dinner, the first order of business was to select an editor-in-chief, at the time an entirely volunteer position. Fritz Lanham (at right) received the nod. A lawyer from Weatherford (just west of Fort Worth), he was best-known on the Forty Acres as the founder and first editor of the Texan newspaper. The group hoped Lanham would bring that experience to the new alumni magazine.

Like Will Hogg, Fritz Lanham was also the son of a former Texas governor. Samuel Lanham held the office from 1903 to 1907, after having served 18 years in the U.S. Congress. Though Fritz never ran for governor, he did follow in his father’s footsteps to Washington, where he represented Texas’ 12th congressional district from 1919 until his retirement in 1946.

Following the choice of Lanham as editor, the board held an animated conversation well into the evening, debating the purpose and content of the magazine. Benedict quipped, “This enthusiasm was, it must be admitted, in part due to the fact that Charles K. Lee, Will Hogg, Dr. David H. Lawrence, and John Philip had agreed to back the proposed magazine to the extent of a couple of thousand in case a deficit should unfortunately arise.” Its pages were to be filled with reminiscences from faculty and alumni, news of current campus events, discussions over University problems, and literary efforts, including poetry.

The publication date was pushed back to March 1, 1913, just before Texas Independence Day on March 2 and the planned alumni events across the state. What better time to distribute the first copy of an alumni magazine than on the day ex-students came together to celebrate Texas and their alma mater?

Perhaps the most anticipated question was the magazine’s title. Professor Barker was chosen to lead a sub-committee to select a name, and the nominations included: The Orange and White, The Bronco, The Lone Star, The Alamo, The Ex-Students’ Record – a nod to the retiring University of Texas Record – and The Alcalde.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The word “alcalde” (al-CAL-day) originated as the 7th century Arabic term “al-qadi,” or, “the judge.” Early Muslim kings, known as caliphs, appointed qadis to administer justice in local civil and criminal cases. When the caliphs expanded the Arabian Empire west across northern Africa, and then north into the Iberian Peninsula in 718, they brought the al-qadi custom with them. Local Spaniards later modified the term to “alcalde,” though it retained much of its original meaning. Eight centuries later, after the Spanish regained control of the peninsula, the conquistadors sailed across the Atlantic to invade what is modern day Mexico, and the alcalde tradition arrived in the New World.

Starting in the 1500s, Spanish military and missionary explorers often designated the chiefs of Native American villages as alcaldes, and the term expanded to mean not only a local magistrate, but the town spokesman. By the time Texas won independence from Mexico in 1836, alcaldes were an integral part of the political and legal landscape north of the Rio Grande. With the founding of the Texas Republic, the system was outdated and replaced.

The term, however, endured. Texas Governor Oran Roberts, who shepherded and then signed the 1881 legislation that created the University and later served as one of UT’s first two law professors, was widely known as the “Old Alcalde.” In his honor, the first campus newspaper, a weekly launched in 1895, was named The Alcalde (above). The publication lasted only two years, but John Lomax had been one of its editors. He thought the title appropriate for a UT alumni magazine, both with its connection to the University’s past and in its purpose as the “town voice” for the alumni. Professor Barker’s subcommittee agreed.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

With the coming of the New Year, the 33rd regular session of the Texas Legislature convened on a sunny and mild January 14, 1913. Higher education was to take a prominent part, and the Hogg Organization had been busy. Secretary Arthur Lefevre authored an extensive survey on the state-funded colleges. Titled, “The State Institutions of Higher Education in Texas: Their Past Services, Future Possibilities, and Present Financial Condition,” it was published in time for the beginning of the session and consulted regularly by lawmakers.

One of the pressing issues was the relationship between UT and A&M. The 1876 Texas Constitution designated the A&M College a “branch” of the University, but UT’s Board of Regents and A&M’s Board of Directors met a week before the session began and agreed to ask the Legislature to formally separate them. The Legislature would need to pass a constitutional amendment that would then be ratified by a statewide vote.

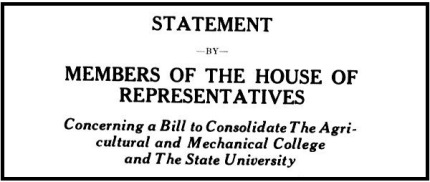

Some lawmakers, though, urged just the opposite, and called for A&M to be merged with the University in Austin, while the College Station campus would be renovated into a “state hospital for the insane.” Arguments for consolidation focused on the costs for maintaining the remote A&M College, with duplicate libraries, labs, and faculty. Lefevre’s study seemed to support a merger. While A&M’s enrollment was less than half of the University (1000 to 2300 UT students), the survey listed the cost per student as more than double ($700 vs. $300 at UT).

On February 5, Texas Governor Oscar Colquitt presented a special message on education. Officially, he was in favor of separating UT and A&M and discussed the constitutional amendment, but he also described his idea of a “Greater University” at length. Colquitt imagined a single campus of “ample acreage” as a place for A&M, a law school, a medical school, the state normal colleges, and arts and industry. “In the center of the campus I would build a magnificent main building of Texas granite,” the governor continued, “and I would call the whole the ‘University of Texas.” To some, it seemed as if Colquitt wanted consolidation on the grandest scale.

The case for a merger was strengthened by headlines from College Station. In January, 27 members of A&M’s Corps of Cadets were dismissed for repeatedly violating hazing rules. On February 1, a petition signed by 466 A&M cadets – nearly half of the student body – was presented to the faculty, insisting their fellow cadets be reinstated. If not, “none of the undersigned men will attend any academic duties from now until such time as our demands are acceded to.” The faculty convened and promptly voted to expel all of the cadets who signed the petition. Eventually, the crisis was solved and the 466 petition signers reinstated (though not the original 27 cadets), but not before the governor became personally involved and the Legislature took time to pass an anti-hazing bill.

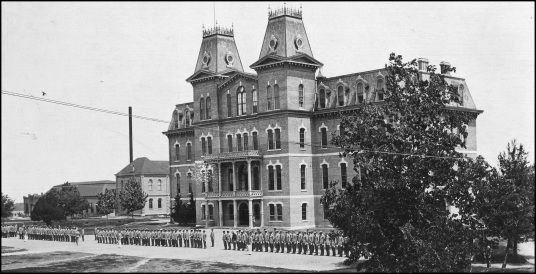

Above: The A&M College’s old Main Building. (Cushing Memorial Library, Texas A&M)

Controversy was no stranger to the A&M College. In 1879, when the College was in its third year, bitter disagreements between professors led to the dismissal of the entire faculty and the president, and two-thirds of the students withdrew. Through the spring of 1908, a series of incidents between President Henry Harrington and the students, investigated twice by the Board of Directors, led to a well-publicized mass exodus of students and ultimately Harrington’s resignation. An early morning kitchen fire destroyed the student mess hall in November, 1911, and just over six months later, in May, 1912, A&M’s original Main Building burned. Only the brick walls were left standing, and most of the College’s records, along with the entire library, were destroyed. The Legislature had to approve additional funds to replace the facilities.

The latest incident, taking place during a Legislative session, only served to increase the volume of the voices who thought A&M should be relocated, and more lawmakers were listening.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: The Southland Hotel in Dallas.

While the Texas Capitol was full of activity, work proceeded on the alumni magazine. On January 30, 1913, the Executive Council met in the Southland Hotel in Dallas. The group officially approved the name Alcalde, set the subscription price at $1 per year (in addition to the $1 Association dues), and created the Alcalde Founders, a designation for alumni who donated $5 a year for five years to support the publication and would then be entitled to a lifetime subscription. The Council also recruited University Registrar Ed Matthews as the magazine’s business manager.

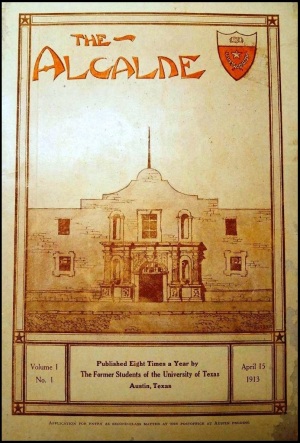

By February, most of the first issue’s content was ready, as Lomax and Lanham had been working for months to secure both authors and articles. Since the magazine was supposed to debut on Texas Independence Day, an image of the Alamo was the choice for the cover. The publication date, though, had to be pushed back yet again to April after Lanham’s wife, Beulah, suffered a near-fatal attack of appendicitis. “My wife was stricken with appendicitis and has been quite sick since,” Lanham wrote to Hogg on February 17. A few days later, Lanham described a “midnight auto trip to Fort Worth for a nurse . . . the doctors concur in the belief that an operation will be necessary as soon as she is able to stand it.”

While his wife convalesced, Lanham created a list of about 300 University friends and sent an appeal for support from his home in Weatherford on March 15. “This is a personal letter, not a waste-basket letter, “Lanham began. “You have likely read about the Alcalde . . . I can imagine nothing which will bind us closer together in our esteem for each other and the University than this publication.” Lanham made his pitch for a $5 annual contribution. “I’m willing to pay my fiver and work hard on the job . . . Don’t pass the ice water; it won’t quench this burning desire we have to do something for the University and each other.” The same day, Lanham took the train to Austin to complete the first issue with Lomax and Matthews.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When Lanham arrived in the capital city, the Legislative debate over whether to separate or merge the University and A&M was at full throttle. The hazing problems in College Station only bolstered the arguments that the A&M campus was too remote. A consolidation bill had been introduced in the House and much of the Legislature supported it.

On March 22, less than two weeks before the session ended on April 1, a pamphlet appeared signed by 12 members of the House. It outlined several reasons for consolidation, including:

- “The recent strike is but the last of a series of similar troubles of the College . . .”

- “These periodic upheavals are not due to the inefficiency of the Faculty and the unruly character of the students, but rather to the location of the College and the conditions under which the students are forced to live.”

- “The State is wasting a large sum of money in maintaining rival engineering schools and in duplication of libraries, laboratories and the teaching staff.”

- “The agricultural and other interests of the State would be better cared for by one strong unified institution like the University of Wisconsin or Illinois . . .”

The pamphlet reprinted editorials from the Houston Chronicle, Dallas Morning News, San Antonio Express, Austin Daily Statesman, Fort Worth Record, and Farm and Ranch. All endorsed a merger. There were recent testimonials from university presidents across the country: Wisconsin, Ohio State, Arkansas, and Minnesota, among them. “I regard the separation of the Agricultural and Mechanical College from the State University as illogical in conception, inefficient in practice, and always wasteful,” wrote Sam Avery, an agriculture professor and Chancellor of the University of Nebraska. “The best scheme I can think of to waste the State’s money is to maintain the college of agriculture and mechanical arts separate from the State University,” stated Ross Hill, President of the University of Missouri. Ben Wheeler, President of the University of California, was direct. “The place for your Agricultural and Mechanical College,” wrote Wheeler,” is undoubtedly at Austin in connection with the State University.” The Texas Cattle Raisers’ Association added its voice, and thought that merging A&M with UT “would be wise and prudent from every point of view.”

Most important was the view of David Houston, who was appointed President of A&M (1902 – 1905), then was UT’s President (1905 – 1908) and was currently serving as the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture under Woodrow Wilson. “The present location of A. and M. is exceedingly unfortunate, agriculturally and educationally,” wrote Houston. “The Faculty and students both suffer . . . Consolidation would result in a great strength for both institutions, and the A. and M. College interests would be the chief gainers . . . In my judgement, the friends of the A. and M. College should be the strongest advocates for the proposal.”

When asked about space for a College farm in Austin, supporters quickly pointed to the 500-acre tract of land along the Colorado River, recently donated to the University in 1910 by San Antonio Regent George Brackenridge (and known today as the Brackenridge Tract). Will Hogg was initially for separation, but gradually changed course, thought it financially prudent to headquarter A&M in Austin, but also wanted it to direct four or five sub-campuses of the College in various parts of the state, with “practical training adapted to the agricultural resources of that section.” When asked about consolidation, Baylor University President Sam Brooks approved of the idea, “properly safeguarding the rights of both institutions and the alumni of both.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The discussion in the Legislature injected eleventh-hour uncertainty with plans for the Alcalde. If the lawmakers passed a constitutional amendment to merge A&M with the University, there were calls to have some kind of article in the magazine about the legislation and the issues. And if the amendment were approved in a statewide vote, it would mean that the A&M alumni organization would merge with the Ex-Students Association, and the magazine would need to reflect the interests and historical memories of A&M alumni as well.

As it was necessary to know the final outcome of the consolidation debate, it was agreed not to send the Alcalde to press until after the session ended April 1.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

As March came to a close, A&M alumni and other supporters rushed to the College’s defense, including six members of the Corps of Cadets who remained at the Capitol for days to personally speak with every lawmaker. Perhaps the most prominent was Clarence Ousley, Chairman of the UT Board of Regents, who wanted to adhere to the January agreement between the regents and A&M Board of Directors and was firmly in favor of separation.

The 33rd Legislative session was set to adjourn at noon on April 1, but the clocks in the Capitol were turned back several times to accommodate the usual last-minute flurry of bills. The final gavel was heard closer to 4:30 in the afternoon.

The House unanimously passed a constitutional amendment to separate the University and A&M, but the Senate favored consolidation, leaving the issue at an impasse and the relationship between UT and A&M unchanged.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Printed, bound, and ready at last, the inaugural issue of the Alcalde was delivered from the publishing house April 15. At just over 100 pages, square bound, and 7 by 10 ½ inches, it better resembled an academic journal than a magazine. The next day, Lomax mailed Hogg the very first printed copy, along with a handwritten note. “I am sending you . . . the first copy of The Alcalde, the real first copy of all copies received from the press . . . to you is due the credit of its appearance . . . For your activity, brain, and generosity is giving life to the whole Alumni movement.” The note was a gracious acknowledgement of Hogg’s support and financial backing, but everyone knew that it was Lomax’s diligent labors which deserved the most praise.

Printed, bound, and ready at last, the inaugural issue of the Alcalde was delivered from the publishing house April 15. At just over 100 pages, square bound, and 7 by 10 ½ inches, it better resembled an academic journal than a magazine. The next day, Lomax mailed Hogg the very first printed copy, along with a handwritten note. “I am sending you . . . the first copy of The Alcalde, the real first copy of all copies received from the press . . . to you is due the credit of its appearance . . . For your activity, brain, and generosity is giving life to the whole Alumni movement.” The note was a gracious acknowledgement of Hogg’s support and financial backing, but everyone knew that it was Lomax’s diligent labors which deserved the most praise.

The cover was yellow (officially “old gold”), with its masthead – “The Alcalde” – and a version of the University’s Seal at the top in orange, and with a large, shaded image of the Alamo in the center, a reminder that the issue was six weeks late. The color choice wasn’t arbitrary; it had deep roots in the University’s history and resonated with the alumni at the time. While orange and white had been formally recognized as UT’s colors in 1900, all of the buildings on campus, except for the new Library, were made from Austin pressed yellow brick and cream limestone trim, still seen today in the Gebauer Building. The use of similar construction materials not only provided a unifying visual element to the Forty Acres, it influenced how students and alumni identified with the University. In 1893, UT’s first football team listed its colors as “old gold and white” and wore yellow beanie caps with black and white jerseys. Gold and white were also contenders in the final color selection in 1900.

Above: The yellow-bricked Gebauer Building.

The Alamo cover design was the product of Ed Connor, a 1905 graduate who earned both engineering and liberal arts degrees. As a student, Connor’s artistic talents were always in demand, especially in the Cactus yearbook. He even spent a summer in Europe to study drawing in Paris.

Connor married into the Lanham family on January 1, 1907, when he wed Governor Lanham’s daughter, Grace, at the first marriage ceremony held in the Governor’s Mansion. As brothers-in-law, Fritz and Ed were close. The Connors named their first child Fritz Lanham Connor after the boy’s uncle. While Connor pursued engineering as a career, he was happy to help when Fritz asked about a cover for the Alcalde.

Just inside the cover, the front matter included a subscription form, the Table of Contents, a full-page ad by the University Co-op, the names of the Executive Council and district secretaries, lists of the Association’s life and endowment members, and names of 58 Alcalde Founders, which would grow to 170 by the end of the year. There was also an Alumni Law Directory for those who paid a small fee to be listed. In future issues, it would expand into a full Professional Alumni Directory, connecting ex-students by their occupations.

President Mezes penned the Foreword. “I rejoice from my heart at the inauguration of The Alcalde,” he wrote. “It should be a bond of ever-growing power tying former students to each other and to Alma Mater. Through it they will learn how fare the others over the broad back of the Earth. Through it they will revive fond memories of their college days . . . Through it they will learn of the progress of the institution to the goal of its ideal and have an orderly record of its life and work.”

Readers were treated to memories of UT’s earliest years written by the late John Mallet and Milton Humphries, the last surviving member of the original faculty. George Carter’s article, “Who Spiked the Canon?” relayed details about UT’s first Texas Independence Day celebration in 1897, when students borrowed a canon from the Capitol and fired it in front of the old Main Building. Another article in the second issue, “The Choosing of the Colors” by Venable Proctor, explained how orange and white was introduced to the University. Without these important contributions, the stories behind some of UT’s popular traditions might have been forever lost.

Here, too, was news from the campus, the latest in Longhorn sports, a lighthearted anecdotal column authored by Dean Harry Benedict, and occasional poetry composed by alumni. Personal updates by class year were listed under the heading, “Texas Exes,” the first time the now-familiar term was published.

Five thousand copies of the first issue were published by the Von-Boechmann-Jones Company in Austin and sent to alumni (subscribers and potential subscribers) as well as those who used to receive the University of Texas Record. Some copies were for sale in Old Main and the University Co-op. Mary Batts, one of the Alcalde’s two student editors, set up a table at the second floor entrance to the Library’s reading room (what today is the Battle Hall library) and did not let a student pass until they subscribed. “Truly the greatest present problem of THE ALCALDE is financial,” wrote Lanham in his editorial column. “This first issue of five thousand copies is put forth on faith.”

The magazine received glowing reviews from the local press. “The contents of the periodical require no apologies on any ground. The articles are timely, interesting, and well written,” declared the Texan. “The Alcalde should find a ready acceptance, not only with the alumni of the University, but with the student body as well.” The Austin Statesman gushed, “In point of print and paper, the Alcalde can lay more claim to art – spelled with a capital A – than any other magazine published in the Southwest.”

Just a few days after the release of the first issue, on April 19, Jessie Andrews, the first woman graduate of the University and its first female instructor, penned a five-stanza poem to welcome the new alumni magazine. It was published in the May 1913 issue:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Epilogue

The Alcalde magazine enjoyed a very adventurous first few years. Among the highlights:

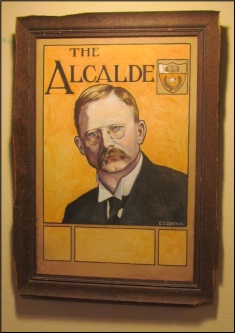

The third issue of the magazine, ready in time for the June 1913 commencement and the University’s 30th anniversary celebration, featured a special cover (right) in tribute to engineering Dean Thomas Taylor and his 25 years on the UT faculty. A popular and respected figure across the campus – known affectionately by the students as the “Old Man” – a color rendering of the rusty-haired Taylor was drawn by Ed Connor, but was published in the usual gold tint. The original version, though, with its weathered and battered frame, still resides in the Alcalde offices in the Alumni Center as one of the few surviving artifacts of the magazine’s first year.

The third issue of the magazine, ready in time for the June 1913 commencement and the University’s 30th anniversary celebration, featured a special cover (right) in tribute to engineering Dean Thomas Taylor and his 25 years on the UT faculty. A popular and respected figure across the campus – known affectionately by the students as the “Old Man” – a color rendering of the rusty-haired Taylor was drawn by Ed Connor, but was published in the usual gold tint. The original version, though, with its weathered and battered frame, still resides in the Alcalde offices in the Alumni Center as one of the few surviving artifacts of the magazine’s first year.

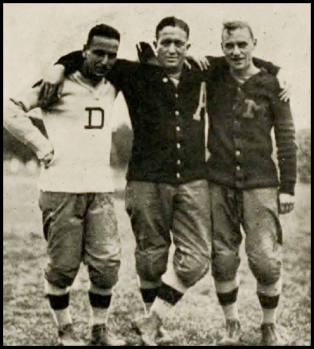

A photo of UT’s football coaches, labeled “Greatest Coaching Staff in the South,” appeared in the November 1913 issue (at right). The image included Assistant Coach Burton Rix, a Dartmouth graduate, Assistant Coach Lt. Joseph Weir from West Point (Army), and Head Coach David Allerdice, who played for the University of Michigan. All three wore their college letter sweaters, which appeared in the photo as “D A M” and sparked a complaint letter to The Daily Texan. “I think that the editors and staff of the Alcalde should at least have a say so as to what goes and leave the ‘cuss’ words out . . . The grouping is excellent, considered from the ‘cussing’ standpoint . . . Now honestly, don’t you think that these figures should have been reversed or changed in some way?” The note was anonymously signed, “J. B.”

A photo of UT’s football coaches, labeled “Greatest Coaching Staff in the South,” appeared in the November 1913 issue (at right). The image included Assistant Coach Burton Rix, a Dartmouth graduate, Assistant Coach Lt. Joseph Weir from West Point (Army), and Head Coach David Allerdice, who played for the University of Michigan. All three wore their college letter sweaters, which appeared in the photo as “D A M” and sparked a complaint letter to The Daily Texan. “I think that the editors and staff of the Alcalde should at least have a say so as to what goes and leave the ‘cuss’ words out . . . The grouping is excellent, considered from the ‘cussing’ standpoint . . . Now honestly, don’t you think that these figures should have been reversed or changed in some way?” The note was anonymously signed, “J. B.”

- On Saturday, March 21, 1914, the University of Texas Ladies Club held its organizational luncheon at the Driskill Hotel in downtown Austin. Along with electing officers and making plans for future activities, Bess Lomax, wife of alumni secretary John Lomax, voiced her disappointment that there were almost no women authors in the Alcalde. She came prepared with copies of a pre-written letter for members to pass along to their friends. “The fact will always remain,” Bess wrote, “for the first twelve months of its existence, the men have written practically all of the Alcalde.” She continued, “I am writing to you as a representative University woman . . . Whatever happens, we must not let the Alcalde become merely a man’s magazine, any more than we would allow Varsity to become only a man’s college.” It wasn’t long before more female bylines appeared in the pages of the magazine.

- With interest in the Alcalde growing, the August 1914 issue was an impressive 200 pages long and included its first color image (above). A photo of the University Library (above), the front balustrade was carefully drawn as it would appear. The decorative railing was part of the building’s original design, but never constructed. As was so often the case during Austin’s warmer months, the windows were open to catch any cooling breezes.

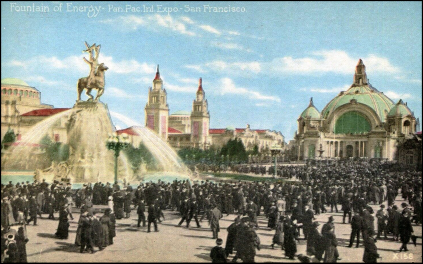

- In 1915, the Alcalde’s high typographical quality and the use of monotype for its cover and other graphics made it a featured publication in the printing exhibit at the San Francisco World’s Fair, as well as the San Diego Panama-Pacific Exhibition in 1916.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources:

Alcalde magazine

University of Texas Record

Briscoe Center for American History (UT Archives): Robert Batts Papers, William J. Battle Papers, Harry Y. Benedict Papers, Will C. Hogg Papers, John A. Lomax Papers, UT Ex-Students Association Records, UT President’s Office Records

Alexander Architectural Archives

UT Board of Regents minutes

House and Senate Journals, 33rd Regular Session of the Texas Legislature

Report of the National Conference of Alumni Secretaries 1913 – 1916

Benedict, Harry. A Sourcebook of University of Texas History (UT Bulletin, 1916)

Dethloff, Henry. A Centennial History of Texas A&M, 1876 – 1976 (Texas A&M, 1976)

Porterfield, Nolan. The Last Cavalier: The Life and Times of John A. Lomax (University of Illinois, 1996)

Newspapers: Austin American-Statesman, The Daily Texan, Galveston Daily News, Fort Worth Telegram, Fort Worth Record and Register, San Antonio Daily Light, Houston Post