“You may tear down the Alamo, but never B. Hall!” – B. Hall Alumni Association

In the storied annals of Texas history, few places could ever compete with the spirit and lore of the Alamo. But for a select group of students who lived on the University of Texas campus from 1890-1926, the Alamo took a back seat to B. Hall.

Nestled on the eastern slope of the Forty Acres, within earshot of the ivy-draped old Main Building, Brackenridge Hall, or simply, “B. Hall,” was the University’s first residence hall. Opened December 1, 1890, it was intended to be an anonymous, unceremonious gift, a low-cost building to provide cheap housing for male students. But the gift of B. Hall grew to be much more. For decades, the hall and its residents were central to campus life. A stronghold of student leadership, the birthplace of UT traditions, championed as a bastion of “Jeffersonian Democracy,” the hall sheltered future Rhodes Scholars, professors, philosophers, lawyers, physicians, state and national lawmakers, U. S. ambassadors, college presidents, a governor of Puerto Rico, and a Librarian of Congress. For a time the hall became so well-known nationally that letters addressed simply to “B. Hall, Texas,” were known to reach their destination. When it was finally razed in the 1950s, the legacy of the hall wasn’t simply a building and its donor. The gift that was B. Hall rested with the indelible contributions its residents had made to the University, and, later, to the world.

Dormitories were not originally planned for the University. Ashbel Smith, the first chair of the Board of Regents (photo at left), was flatly opposed to them. “It is even worse than a pure waste of money. Nor should there be a college commons where students eat in mess. Experience is decisive on these points.” By experience, Smith knew of the raucous student rebellions that had plagued Harvard and Princeton and left their dorms in shambles, and of a violent incident at the University of Virginia in which a professor was shot and killed. All of these events involved young men housed together on the campus, which left many college authorities hesitant to build dorms. Cornell’s first president, Andrew White, hoped the hometown citizens of Ithaca, New York would provide room and board. White wrote in 1866, “Large bodies of students collected in dormitories often arrive at a degree of turbulence which small parties, gathered in the houses of citizens, seldom if ever reach.” Manasseh Cutler, a Massachusetts botanist who helped to settle Ohio and found Ohio University, was more direct: “Chambers in colleges are too often made the nurseries of every vice and cages of unclean birds.”

Dormitories were not originally planned for the University. Ashbel Smith, the first chair of the Board of Regents (photo at left), was flatly opposed to them. “It is even worse than a pure waste of money. Nor should there be a college commons where students eat in mess. Experience is decisive on these points.” By experience, Smith knew of the raucous student rebellions that had plagued Harvard and Princeton and left their dorms in shambles, and of a violent incident at the University of Virginia in which a professor was shot and killed. All of these events involved young men housed together on the campus, which left many college authorities hesitant to build dorms. Cornell’s first president, Andrew White, hoped the hometown citizens of Ithaca, New York would provide room and board. White wrote in 1866, “Large bodies of students collected in dormitories often arrive at a degree of turbulence which small parties, gathered in the houses of citizens, seldom if ever reach.” Manasseh Cutler, a Massachusetts botanist who helped to settle Ohio and found Ohio University, was more direct: “Chambers in colleges are too often made the nurseries of every vice and cages of unclean birds.”

Above: In 1889, only two-thirds of the old Main Building was completed. The two children in the front are sitting among bluebonnets about where Sutton Hall is today.

As the University of Texas opened for its seventh academic year in the fall of 1889, enrollment exceeded 300 students for the first time, with almost two thirds of them men. As there was no campus housing, most students found room and board in private homes around Austin for about $25 per month. Additional costs included an annual matriculation fee of $10, a $5 library deposit, and the purchase of textbooks. Tuition for in-state students didn’t yet exist, so that a year at UT could easily be had for less than $300.

That might sound inexpensive, but the cost of living in Austin was too high for many college-aged youth in Texas. At the time, almost 90% of the state’s population was classified as rural, struggling against the Southern agricultural depression of the late 1880s. Poverty conditions were widespread among the farms and ranches of Texas, where eggs brought in just two cents per dozen, cotton netted four cents a pound, and a healthy steer earned five to eight dollars. Young men raised in these conditions, known as the “poor boys” of the state, sought a way out, and looked to the University as a promising opportunity for social mobility.

When the Board of Regents convened in February 1890, George Brackenridge, a wealthy San Antonio banker and University regent, offered up to $17,000 to build an economical residence hall for the state’s poor boys. He preferred to keep his donation anonymous and requested the building be named “University Hall.” His fellow regents, though, wanted to encourage a similar gift for a dormitory for women, and persuaded the reluctant donor to allow the building to be named for him. (They did, though it was from Brackenridge again.) Students would later shorten the name from Brackenridge Hall to simply “B. Hall.”

Above: The original B. Hall, opened in 1890. The house down the hill to the right sat along Speedway Street and would today be in the middle of the East Mall.

Completed on December 1, 1890, the original hall was a plain, no-frills structure, made from pressed yellow brick and limestone trim. Four stories tall, with simple bay windows and two front doors facing west, it better resembled a pair of low-cost city townhouses adrift on the Texas prairie.

Above: The Forty Acres in the 1890s as seen from 21st and Guadalupe Streets. Old Main is in the middle of the campus, with B. Hall to the right.

Initially, Brackenridge Hall housed 48 men and could accommodate more than 100 persons in its ground floor restaurant, which doubled as the first campus-wide eatery. Rent was initially set at $2.50 per month for a room, and meals could be had for less than $10 monthly, half the usual cost of living in Austin by half.

Above: The B. Hall menu for Thanksgiving Day, 1892. Check out the prices and the inside jokes with the quotations. Source: UT Memorabilia Collection, Box 4P158, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

A decade after it opened – thanks to another donation from George Brackenridge – the hall was renovated and expanded to house 124 students. Wings were added on the north and south ends, an open community room was built above the top floor, and towers, turrets, and a red tin roof helped to improve its humble facade.

Above: In 1899, wings were added to the north and south sides of original building.

B. Hall provided young men in Texas with limited finances the opportunity to attend the University. Many of them were the sons of pioneers, born in log cabins and raised with few luxuries. Practical, self-motivated, and individualistic, all of them were poor. Often equipped with a single change of clothes, some would ride into Austin on horseback, sell their horses, and use the money to help pay for a year’s stay. Almost all held part-time jobs while they were students.

What the hall’s residents lacked in pocket change, they more than made up for in character. From the Texas range they brought with them the best attributes of frankness and determination, and their shared economic status provided them with a common motivation. With limited opportunities to attend school in rural Texas, many had no high school diplomas. They had to prepare themselves for college-level classes and were conditionally admitted through examination. Ages varied from 18 to just over 30.

Sometimes shunned by more affluent UT students, the occupants of B. Hall developed their own fraternal, close-knit community. Academics were taken seriously. Most of the honors students, along with the University’s first Rhodes Scholars, lived in the hall. Professors were frequent guests for dinner and often stayed for the post meal “pow-wow,” held in the dining hall or in the shade on the east side of the building. For an hour or so at dusk each evening, faculty and students engaged in a lively conversation on current affairs, campus issues, or academic topics. “The student that missed the daily pow-wow,” wrote one B. Hall alumnus, “never knew what University life at its fullest really meant.”

Above: Two engineering roommates in B. Hall.

Strong friendships developed between the hall’s residents, as mutual support was always encouraged, and sometimes required. The University’s first visually impaired students lived in B. Hall, among them Olan Van Zandt, who graduated from the Texas School for the Blind to enroll in the law school. None of the texts were written in braille, and recordings weren’t available. Instead, Olan’s fellow denizens spent untold hours reading to him and reviewing torts, contracts, and equity. Van Zandt graduated with honors and went on to serve in the Texas Legislature: four sessions in the House, and another four sessions in the Senate.

Along with classes, B. Hall occupants took an active part in UT affairs, voted for themselves in student elections, and were recognized as campus leaders. Their contributions to the University were many and long lasting. The origins of The Eyes of Texas, Texas Taps (“Texas Fight”), student government, The Daily Texan, UT’s first celebration of Texas Independence Day, the Longhorn Band, and even the purchase of the steer that became the longhorn mascot Bevo are all connected to B. Hall. Three of the hall’s alumni: Dr. Harry Benedict, the first alumnus to be appointed UT president; Dr. Gene Schoch, a noted chemical engineering professor who founded the Longhorn Band; and Arno Nowonty, the immensely popular Dean of Student Life, have campus buildings named for them.

Along with classes, B. Hall occupants took an active part in UT affairs, voted for themselves in student elections, and were recognized as campus leaders. Their contributions to the University were many and long lasting. The origins of The Eyes of Texas, Texas Taps (“Texas Fight”), student government, The Daily Texan, UT’s first celebration of Texas Independence Day, the Longhorn Band, and even the purchase of the steer that became the longhorn mascot Bevo are all connected to B. Hall. Three of the hall’s alumni: Dr. Harry Benedict, the first alumnus to be appointed UT president; Dr. Gene Schoch, a noted chemical engineering professor who founded the Longhorn Band; and Arno Nowonty, the immensely popular Dean of Student Life, have campus buildings named for them.

Above left: The original lyrics of The Eyes of Texas, written on a scrap of laundry paper in room 203 of B. Hall by John Lang Sinclair.

Above: In 1900, Gene Schoch purchased 16 musical instruments at a downtown Austin pawn shop, and then recruited a group of B. Hall residents to form what is today the Longhorn Band.

While most college dorms were heavily supervised by campus administrators, UT officials allowed the hall’s denizens to largely manage themselves. While there was a hired steward to look after finances, the students created their own B. Hall Association, wrote a constitution and by-laws, and enacted their own regulations. A suit and tie was required dress for all meals, musical instruments could only be played between 1-2 pm. and 5-7:30 p.m., and card playing was expressly prohibited.

Above: The Rustic Order of Ancient and Honorable Rusty Cusses was a very non-serious social club of B. Hall men who hailed from farms and ranches around Texas. Several campus organizations were born within the confines of B. Hall, including the Texas Cowboys and the Tejas Club.

That doesn’t mean life in the hall was all serious business. With little money for entertainment, the hall’s occupants often had to create their own diversions, and a favorite pastime was staging elaborate practical jokes. One student discovered he was a great voice impersonator and, pretending to be University President Sidney Mezes, called professors and instructed them to “be at my house tonight at 8 to discuss a serious matter.” Harried faculty members showed up unexpectedly at Dr. Mezes’ front door. Another B. Haller physically masqueraded as the UT president and registered most of the freshmen with fake papers, which resulted in a very interesting first day of class. A lost donkey was led into the women’s dorm as a late night gift on Halloween. In search of a new morning wake-up alarm, some hall residents “borrowed” a bell from the Fulmore School in South Austin. When a few B. Hallers tricked the Texas Legislature into officially inviting a world famous pianist to the State Capitol to “sing” his most famous piece, the incident created national headlines. As Engineering Dean Thomas Taylor, a regular guest at the hall, once remarked, “Barely a week passed by that some freakish cuss did not spring something entirely original, and not half of it ever got into the newspapers or magazines.” Many of the antics became legendary and the stories were passed along to succeeding generations of students.

After graduation, when the “poor boys” of B. Hall had completed their hard won degrees, they set out to make to the most of their education. Along with an impressive list of professors, lawyers, judges, authors, state legislators, engineers, and physicians, the alumni roster included a Librarian of Congress, a governor of Puerto Rico, multiple U.S. ambassadors, Morris Sheppard and Ralph Yarborough as U.S. Senators, and Sam Rayburn as Speaker of the House.

Most of the alumni maintained a lifelong, cherished attachment to the hall, often visited when they were in Austin, and were welcome guests. Prodded by the current occupants to tell stories of the “old times,” alumni shared their UT adventures, along with their experiences after graduation, and in the process inspired the generation of students.

By the 1920s, as University enrollment surpassed 4,000 students, B. Hall was still the only on campus men’s dorm. Though it was no longer a designated refuge for the “poor boys” of the state, it was still less expensive than other housing options and in high demand. The hall’s popularity meant that most rooms went to upperclassmen or older students, who were solid academically and already involved as campus leaders.

By the 1920s, as University enrollment surpassed 4,000 students, B. Hall was still the only on campus men’s dorm. Though it was no longer a designated refuge for the “poor boys” of the state, it was still less expensive than other housing options and in high demand. The hall’s popularity meant that most rooms went to upperclassmen or older students, who were solid academically and already involved as campus leaders.

Above left: Where on campus was B. Hall? This photo, taken from the Tower observation deck in the 1940s, shows the hall straddled what today is the East Mall. Immediately behind the building is Waggener Hall and Gregory Gym, with the stadium in the upper left.

However, the building itself was in the way of future campus development. In 1925, the Board of Regents decided that B. Hall was too close to Garrison Hall – then under construction – to remain a dormitory. Garrison was to be a co-ed classroom building. According to the regent’s minutes, “young women should not be required to attend classes in full view of the bedrooms of men, particularly in a dormitory where freedom in matters of clothing is well-known.” Alumni of the hall loudly protested, organized into a formal B. Hall Alumni Association, and threatened legal action. (The Association’s president was, appropriately, Walter Hunnicutt, the composer of the “Texas Fight!” song.) Before the situation became too tense, University officials and alumni settled on a compromise: the current B. Hall could be re-purposed if a new Brackenridge Hall was built on a more appropriate site.

The hall was closed in 1926, renovated, and served, among other things, as the first home of the School of Architecture until it moved into more spacious quarters at Goldsmith Hall. In 1932, a new Brackenridge residence hall was formally dedicated on 21st Street.

Above: A new Brackenridge Hall was opened in 1932, just south of Gregory Gym.

B Hall was finally razed in 1952 to clear the way for the East Mall. As it was being demolished, the contractor did his best to satisfy the many requests from alumni for specific bricks, doors, floorboards, and other pieces of the building. Former Austin Mayor Walter Long also ensured that some parts of the hall were kept and preserved by the University. One of those pieces, a decorative pediment from the roof, spent decades in storage at the Pickle Research Center, but has been restored and is now on display in Jester Center, just outside the auditorium.

Above: it’s still possible to see a piece of old B. Hall. A decade ago, the author discovered a decorative piece from the building in a warehouse at UT’s Pickle Research Center in north Austin, sitting on top of a pile of dusty boxes that contained the clock from the old Main Building (upper left). Thanks to funding from the UT Division of Housing and Food and the Texas Exes, the six foot tall piece was restored and is now hanging in Jester Center (above center), complete with a story board. The piece comes from the top floor of B. Hall (upper right, highlighted in brown).

The UT History Corner has passed the 500,000 visitor mark. A sincere and humble thanks goes to everyone who has taken time to read, look, listen, or just browse through some of the history of the University of Texas. I hope you found something here worth your time.

The UT History Corner has passed the 500,000 visitor mark. A sincere and humble thanks goes to everyone who has taken time to read, look, listen, or just browse through some of the history of the University of Texas. I hope you found something here worth your time.

Dormitories were not originally planned for the University. Ashbel Smith, the first chair of the Board of Regents (photo at left), was flatly opposed to them. “It is even worse than a pure waste of money. Nor should there be a college commons where students eat in mess. Experience is decisive on these points.” By experience, Smith knew of the raucous student rebellions that had plagued Harvard and Princeton and left their dorms in shambles, and of a violent incident at the University of Virginia in which a professor was shot and killed. All of these events involved young men housed together on the campus, which left many college authorities hesitant to build dorms. Cornell’s first president, Andrew White, hoped the hometown citizens of Ithaca, New York would provide room and board. White wrote in 1866, “Large bodies of students collected in dormitories often arrive at a degree of turbulence which small parties, gathered in the houses of citizens, seldom if ever reach.” Manasseh Cutler, a Massachusetts botanist who helped to settle Ohio and found Ohio University, was more direct: “Chambers in colleges are too often made the nurseries of every vice and cages of unclean birds.”

Dormitories were not originally planned for the University. Ashbel Smith, the first chair of the Board of Regents (photo at left), was flatly opposed to them. “It is even worse than a pure waste of money. Nor should there be a college commons where students eat in mess. Experience is decisive on these points.” By experience, Smith knew of the raucous student rebellions that had plagued Harvard and Princeton and left their dorms in shambles, and of a violent incident at the University of Virginia in which a professor was shot and killed. All of these events involved young men housed together on the campus, which left many college authorities hesitant to build dorms. Cornell’s first president, Andrew White, hoped the hometown citizens of Ithaca, New York would provide room and board. White wrote in 1866, “Large bodies of students collected in dormitories often arrive at a degree of turbulence which small parties, gathered in the houses of citizens, seldom if ever reach.” Manasseh Cutler, a Massachusetts botanist who helped to settle Ohio and found Ohio University, was more direct: “Chambers in colleges are too often made the nurseries of every vice and cages of unclean birds.”

Along with classes, B. Hall occupants took an active part in UT affairs, voted for themselves in student elections, and were recognized as campus leaders. Their contributions to the University were many and long lasting. The origins of The Eyes of Texas,

Along with classes, B. Hall occupants took an active part in UT affairs, voted for themselves in student elections, and were recognized as campus leaders. Their contributions to the University were many and long lasting. The origins of The Eyes of Texas,

By the 1920s, as University enrollment surpassed 4,000 students, B. Hall was still the only on campus men’s dorm. Though it was no longer a designated refuge for the “poor boys” of the state, it was still less expensive than other housing options and in high demand. The hall’s popularity meant that most rooms went to upperclassmen or older students, who were solid academically and already involved as campus leaders.

By the 1920s, as University enrollment surpassed 4,000 students, B. Hall was still the only on campus men’s dorm. Though it was no longer a designated refuge for the “poor boys” of the state, it was still less expensive than other housing options and in high demand. The hall’s popularity meant that most rooms went to upperclassmen or older students, who were solid academically and already involved as campus leaders.

On December 1, 1890, the University opened Brackenridge Hall, known on campus simply as “

On December 1, 1890, the University opened Brackenridge Hall, known on campus simply as “

The following year, November 26, 1891, the first Thanksgiving Day meal was served in B. Hall. As most of the residents were too poor to afford a train ticket home, the hall’s steward, Harry Beck, had a feast prepared and a special menu printed on 4 ½ x 7 inch cards. Though the menu has not survived, it was published in the Austin Statesman.

The following year, November 26, 1891, the first Thanksgiving Day meal was served in B. Hall. As most of the residents were too poor to afford a train ticket home, the hall’s steward, Harry Beck, had a feast prepared and a special menu printed on 4 ½ x 7 inch cards. Though the menu has not survived, it was published in the Austin Statesman.

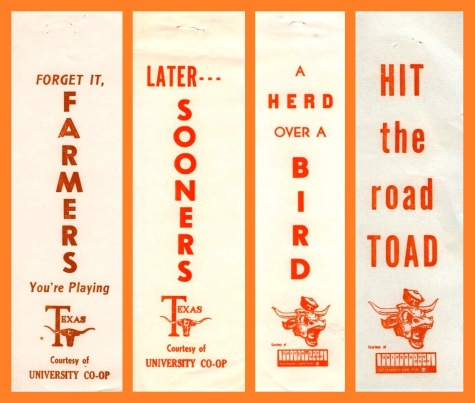

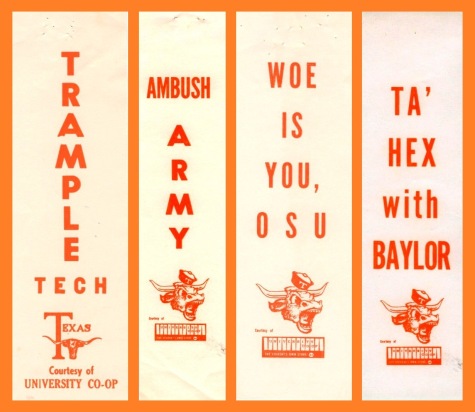

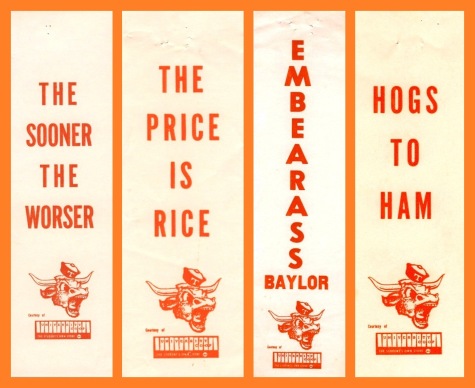

Enter Bill Bates.Originally from Tyler, Texas, Bates transferred to UT for his junior and senior years, 1949-1951. An art major, he had classes with Fess Parker (who would become famous as Disney’s Davy Crockett as well as the Daniel Boone TV series), and for a time dated Cathy Grandstaff, the future Mrs. Bing Crosby. A UT cheerleader, Bates was also a artist for The Daily Texan. He would later travel the world as artist-in-residence for Royal Viking Cruise Ships, then settle in Carmel, California as a cartoonist for the local Carmel Pine Cone. Twice Bates was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. He passed away in 2009, survived by his wife and daughter.

Enter Bill Bates.Originally from Tyler, Texas, Bates transferred to UT for his junior and senior years, 1949-1951. An art major, he had classes with Fess Parker (who would become famous as Disney’s Davy Crockett as well as the Daniel Boone TV series), and for a time dated Cathy Grandstaff, the future Mrs. Bing Crosby. A UT cheerleader, Bates was also a artist for The Daily Texan. He would later travel the world as artist-in-residence for Royal Viking Cruise Ships, then settle in Carmel, California as a cartoonist for the local Carmel Pine Cone. Twice Bates was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. He passed away in 2009, survived by his wife and daughter. Bates was a regular at Bimbo’s 365 Club (photo at left), a nationally known San Francisco nightclub. Founded in 1931 by Italian immigrant Agostino Giuntoli – nicknamed “Bimbo” by friends who had trouble pronouncing his name. (Unlike the current American slang, “bimbo” comes from the Italian “bambino,” a young boy. The nickname was fairly common.) The 365 Club was a place to see and be seen through much of the 20th century. Hollywood celebrities were frequent customers. Rita Cansino, better known as the actress Rita Hayworth, was discovered there. Now more than 80 years old, the

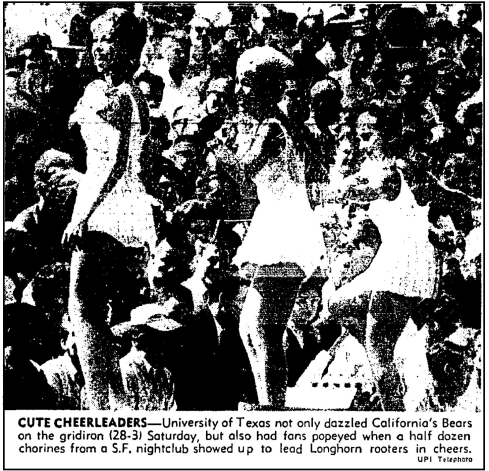

Bates was a regular at Bimbo’s 365 Club (photo at left), a nationally known San Francisco nightclub. Founded in 1931 by Italian immigrant Agostino Giuntoli – nicknamed “Bimbo” by friends who had trouble pronouncing his name. (Unlike the current American slang, “bimbo” comes from the Italian “bambino,” a young boy. The nickname was fairly common.) The 365 Club was a place to see and be seen through much of the 20th century. Hollywood celebrities were frequent customers. Rita Cansino, better known as the actress Rita Hayworth, was discovered there. Now more than 80 years old, the  A football game was taking place on the field, but a good many fans – and players – were more than a little distracted by the spectacle on the sidelines. “University of Texas rooters more or less disrupted the Cal – Texas football game Saturday by hiring a half dozen chorus girls from a San Francisco night club to act as cheerleaders,” reported The Los Angeles Times (photo right). “The girls, scantily clad in lowcut playsuits and wearing high heels, attracted nearly as much attention from the fans as did the football players.During the times-out and half-time ceremonies, thousands of binoculars stayed glued on the field to watch the girls,” which likely included the reporter. “At halftime a mob scene developed where the dancers were sitting as thousands of college students gathered around just to look.”

A football game was taking place on the field, but a good many fans – and players – were more than a little distracted by the spectacle on the sidelines. “University of Texas rooters more or less disrupted the Cal – Texas football game Saturday by hiring a half dozen chorus girls from a San Francisco night club to act as cheerleaders,” reported The Los Angeles Times (photo right). “The girls, scantily clad in lowcut playsuits and wearing high heels, attracted nearly as much attention from the fans as did the football players.During the times-out and half-time ceremonies, thousands of binoculars stayed glued on the field to watch the girls,” which likely included the reporter. “At halftime a mob scene developed where the dancers were sitting as thousands of college students gathered around just to look.”