The 1904 start of the infamous “feud” between engineering and law students.

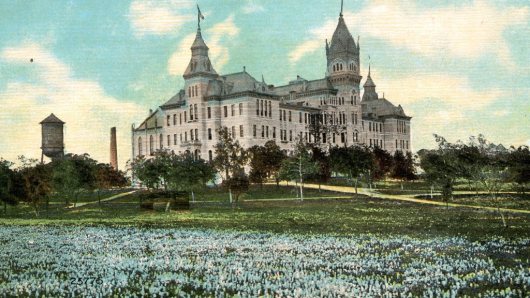

It arrived late in the summer of 1904, when a near-vacant campus was quietly wilting under the August heat. A stark-black and spindle-legged water tank was installed just north of the old Main Building. Intended to be temporary – a year or two at the most – it remained for almost two decades. An instant campus landmark, the tank provided a backdrop for many campus shenanigans, and was the catalyst for a long-lasting rivalry between law and engineering students.

It arrived late in the summer of 1904, when a near-vacant campus was quietly wilting under the August heat. A stark-black and spindle-legged water tank was installed just north of the old Main Building. Intended to be temporary – a year or two at the most – it remained for almost two decades. An instant campus landmark, the tank provided a backdrop for many campus shenanigans, and was the catalyst for a long-lasting rivalry between law and engineering students.

The need for a tank was born in 1900, when a spring flood brought down the seven-year old Austin Dam that had created Lake Austin. City water service was interrupted and remained sporadic for years, and the frequent water shortages forced Austinites to make emergency plans until the water supply was dependable again.

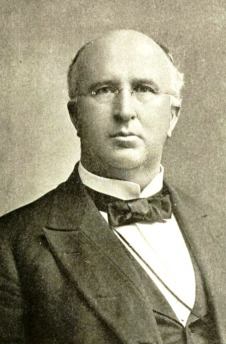

Just before the start of the 1904-05 academic year, UT President William Prather ordered the elevated water tank constructed behind the auditorium of Old Main. Dubbed “Prexy Prather’s Pot” by the students (“Prexy” was slang for “President” at the time.), it towered 120 feet on four lattice supports and stood “in somber majesty on the open campus, in its coat of black paint.” The tank cost just over $11,000, but after it was ready and tested, the University discovered that the city could only provide enough water pressure to fill the tank halfway, making it almost useless. Even worse, the tank leaked, and a permanent pool of mud formed directly beneath it. Fortunately, the University didn’t experience a water emergency, but a lonely water tank on a college campus isn’t likely to be friendless for very long. It soon became a focal point for student antics.

Above: The water tank sat behind the old Main Building, fairly close to the north edge of campus at 24th Street, about where Inner Campus Drive passes the west side of Painter Hall today. Its height enticed students to climb up and enjoy the view, and to paint class numerals and other decorations.

On the brisk autumn morning of October 13th, about two months after the tank’s arrival, the campus awoke to find that the junior law class (the first-year law students) had scaled the ladder attached to the northwest support and decorated the sides of the tank with white paint. The initials of the 1907 Law Class – “0L7” – were boldly displayed, along with “Beware Freshie” and some derogatory remarks about freshmen, especially first year engineering students.

“Every time we viewed the shameful sight, it burned deeper into our seared vision,” wrote Alf Toombs, then a freshman engineer. While the junior laws’ handiwork taunted from above, the engineering freshmen huddled all day and plotted their revenge. Toombs acquired a large sheet of tough paper, and drew “by aid of a bottle of Whitmore’s black shoestring dressing, the silhouette of a jackass of noble proportions, and with the brand of the ’07 Laws on his flank.”

The choice of the animal wasn’t arbitrary. In 1900, law professor William Simkins was lecturing to his first-year Equity class in Old Main and had asked a student about the day’s lesson. Before he could respond, a mule grazing outside the classroom window brayed. “Gentlemen,” said Simkins above the laughter, “one at a time!” Thereafter, junior law classes were nicknamed “Simkins’ Jackasses,” or simply, the “J.A.s.”

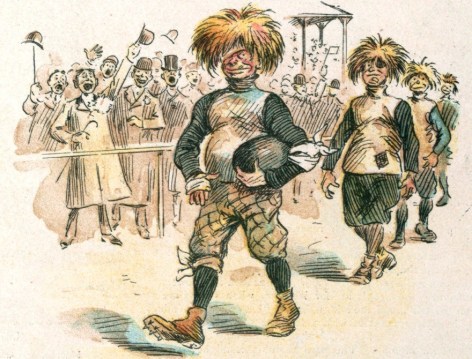

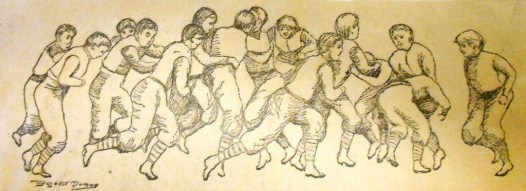

Shortly after dinner that evening, the “clans of the engineers” gathered around the water tank, shouted class cheers and yells of defiance, and dared the law students to dislodge them. “Mars was the ruling planet in the horoscope for University students for several days,” noted The Texan campus newspaper. The junior laws responded accordingly, and amassed to face off against their campus rivals. Once begun, the freshman scrap sprawled over a half-acre and lasted almost an hour. “I entered the melee with a full wardrobe,” Toombs recounted, “and emerged minus a sweater, shirt, cap and part of my ‘munsing-wear,’ not to mention about four square inches of skin.” Though the junior law students were generally older and stronger, the engineers held a numerical advantage. As opportunities arose, unwary laws were captured and “baptized” in the mud pool below the water tank. The battle didn’t subside until the both groups were exhausted, and the muddy and overpowered junior laws had retreated, at least temporarily.

Shortly after dinner that evening, the “clans of the engineers” gathered around the water tank, shouted class cheers and yells of defiance, and dared the law students to dislodge them. “Mars was the ruling planet in the horoscope for University students for several days,” noted The Texan campus newspaper. The junior laws responded accordingly, and amassed to face off against their campus rivals. Once begun, the freshman scrap sprawled over a half-acre and lasted almost an hour. “I entered the melee with a full wardrobe,” Toombs recounted, “and emerged minus a sweater, shirt, cap and part of my ‘munsing-wear,’ not to mention about four square inches of skin.” Though the junior law students were generally older and stronger, the engineers held a numerical advantage. As opportunities arose, unwary laws were captured and “baptized” in the mud pool below the water tank. The battle didn’t subside until the both groups were exhausted, and the muddy and overpowered junior laws had retreated, at least temporarily.

Flushed with their victory, the engineers recruited Toombs, along with fellow freshmen Clarence Elmore and Drury Phillips, to climb and redecorate the water tank. The ascent was a perilous one, as the ladder only went as far as the bottom of the parapet that guarded the service platform. Each of the three would have to grab the parapet, hang by their arms, and swing their legs up and over the railing to get a foothold. Since the law students had done this the night before, the three were certain they could “do all a miserable law could do,” and set out on their mission. Armed with white paint, paintbrushes and Toombs’ sign, the group brought along a pair of blankets each, as they planned to stay and guard their work through the chilly night.

The law students’ graffiti was replaced by a skull and crossbones, class initials “C.E. ‘08” and “E.E. ‘08” for the civil and electrical engineers, along with, “Down with the Laws,” and “Malted Milk for Junior Laws.” Toombs’ painting, “a meek, symbolic jackass, branded 0L7,” was hung in a prominent position. Before bedding down for the night atop the water tank, the three discussed what to do if the laws should return. As one of them had brought along some chewing tobacco, it was decided that if their “fort” was invaded, all of them would “chew tobacco for dear life and expectorate on the attacking party.” A late-night visit by four freshmen in the Academic Department caused some alarm, and the defense was employed. The pleading Academs insisted that they only wanted to add their own class initials to the side of the tank. After some heated deliberation, the engineers grudgingly consented. The rest of the night passed quietly, but it was a miserable one for Toombs. “You see, I was not a user of tobacco, and my gallant defense got the best of me. I was deathly sick for two hours.”

The tank’s revised appearance had the campus buzzing the following morning, and the talk continued for weeks. Engineers and Laws both claimed victory, and expressed their views poetically in “The Radiator” column of The Texan. The law students boasted:

Take your dues, ye engineers. Take a mudding mid the jeers of the ‘Varsity’s population –Simkins’ Equity is just. And the Laws will, when they must, give to you its application.

While the engineers parried:

That same night the Engineers, a noisy, noisome crowd, took lessons in high art at which no Law man was allowed. And those few Laws that hung around, knew not which way to turn. On every hand the enemy,whose need seemed to be stern.

President Prather, though, was not amused, and by mid-morning had hired someone to repaint the entire tank in gray and remove the ladder. Of course, this only provided an irresistible challenge to the students, and the water tank was regularly decorated through the rest of the academic year.

When Dr. David Houston succeeded Prather as president in 1905, he adopted a different strategy, and told the students they were welcome to paint the tank as often as they wished. This took all of the fun out of the deed, and the tank was neglected for years. William Battle, a Greek and Classics professor who had also founded the University Co-op and designed the UT Seal, rose through the academic ranks and in 1914 was appointed acting president. His attitude was “touch not,” which promptly re-ignited student interest. The tank was decorated once more, including a 1915 incident where several professors had to guard the tank overnight.

The water tank remained on the campus through World War I. Along with the usual class initials and slogans, the tank sported the insignias of the military schools stationed at the University through the war, including a particularly well-done mural of a bi-plane painted by a soldier in the School for Military Aeronautics.

The water tank remained on the campus through World War I. Along with the usual class initials and slogans, the tank sported the insignias of the military schools stationed at the University through the war, including a particularly well-done mural of a bi-plane painted by a soldier in the School for Military Aeronautics.

In 1919, the tank was sold to a Houston contractor for $2,000 and finally removed. Its passing was eulogized in the student newspaper: “Our old historic and beloved tank is no more. This old tank was to the University what the Statue of Liberty at the entrance to New York Harbor is to the lover of American democracy. It is the embodiment and emblem of all the splendid traditions, good or bad, of this still more splendid institution.”